So the structure of dandelions is pretty cool. But the genetics are even cooler.

So the structure of dandelions is pretty cool. But the genetics are even cooler. Dandelions are angiosperms, and even though I have yet to explain the amazingly elegant and complex mechanics of angiosperm reproduction, at a chromosomal level it (usually) works a lot like mammalian, or even human, reproduction: Every offspring has 2 parents. One parent- the male- provides a sperm. The other- the female- provides and houses an egg, or specifically an ovule. The sperm and the ovule both have ½ the number of the organisms standard, or fully diploid, number of chromosomes, and are said to be haploid.

Humans have 46 chromosomes, so each of our haploid sex cells has 23 chromosomes. Dandelions have 16 chromosomes, so each of their haploid sex cells has 8 chromosomes. Dandelion flowers are visited by bumblebees collecting nectar who inadvertently spread pollen from flower to flower, thereby pollinating various dandelions. And that’s how dandelions reproduce.

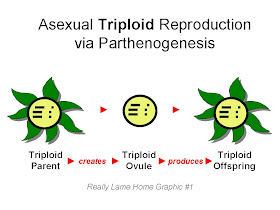

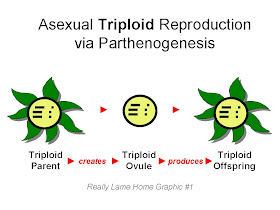

Only most of the time, it’s not. The vast majority of dandelions, including probably every dandelion you have ever seen (assuming you live in the continental US) is a chromosomal triploid that was created asexually from a parthenogenetic parent.

Side note: “triploid” is the specific instance of polyploidy- which we talked about when we looked at Sagebrush in the Newfoundland Mountains- in which the cell contains 3 sets of chromosomes, like a banana. (Only bananas can’t reproduce parthenogenetically.) So a triploid dandelion has 24 chromosomes.

That’s right, virtually all of the dandelions in your yard and your office park have not 16 but 24 chromosomes, and their ovules don’t need or accept pollen from other dandelions. Instead, they reproduce via a process called apomixis (or technically agamospermy in angiosperms) whereby ovules are created without meiosis, are therefore fully triploid right from the get-go, and set to develop into seeds without fertilization.

That’s right, virtually all of the dandelions in your yard and your office park have not 16 but 24 chromosomes, and their ovules don’t need or accept pollen from other dandelions. Instead, they reproduce via a process called apomixis (or technically agamospermy in angiosperms) whereby ovules are created without meiosis, are therefore fully triploid right from the get-go, and set to develop into seeds without fertilization.

But some dandelions are sexual diploids and reproduce according to the standard angiosperm model. But to see this, we should leave Utah and North America for the moment and head back to Europe, the native home of Taraxacum officianale.

But some dandelions are sexual diploids and reproduce according to the standard angiosperm model. But to see this, we should leave Utah and North America for the moment and head back to Europe, the native home of Taraxacum officianale.

T. officianale in Central and Southern Europe are overwhelmingly sexual diploids that reproduce according to the standard angiosperm model. T. officianale in Northern Europe are almost all asexual triploids that reproduce parthenogenetically. But in several areas, such as the Netherlands and the Czech Republic, the triploids and diploids exist side-by-side.

T. officianale in Central and Southern Europe are overwhelmingly sexual diploids that reproduce according to the standard angiosperm model. T. officianale in Northern Europe are almost all asexual triploids that reproduce parthenogenetically. But in several areas, such as the Netherlands and the Czech Republic, the triploids and diploids exist side-by-side.

And now it gets even weirder. Some portion of the asexual triploids still produce viable pollen. Their sperm cells are diploid, and when they fertilize sexual diploid dandelions, they combine with the haploid ovule to create new asexual, parthenogenetic triploid lines. So new triploid lines are continually being created. Some of these lines exhibit high fitness and expand their ranges either locally, or when their seeds are introduced to a new locale, such as North America. And this is why there’s so little agreement on the number of dandelion species- which of these triploid lines are species, which are subspecies, and which are variants?

Side note: The triploid T. officianale- particularly those that don’t manufacture significant pollen- seem to realize a productivity benefit: they produce more seeds than their diploid brethren.

Side note: The triploid T. officianale- particularly those that don’t manufacture significant pollen- seem to realize a productivity benefit: they produce more seeds than their diploid brethren.

T. officianale is therefore a species that has effectively hedged its bets when it comes to sex. When it has a good genetic model it runs with it asexually, but it still dabbles in sex to try out new lines from time to time, as a hedge against any possible threat (disease, parasite, predator) to which a given specific line might be vulnerable. It’s a reproductive schema far more sophisticated and nuanced than any of the other plants we’ve yet looked at, or our own for that matter.

Still another side note: The other day, when I was driving across town, past the House of 1000 Dandelions and such, I was struck by how much is blooming down in Salt Lake City proper as compared to up by my house. The elevation difference is only about 400-500 ft, but spring in downtown is in full swing with forsythia, tulips, daffodils, and various red, white or purple tree blossoms. Up by my house (4,800 feet), we’re just starting to see bits of color: I snapped this forsythia bush about a block from my house on the way home last night.

Still another side note: The other day, when I was driving across town, past the House of 1000 Dandelions and such, I was struck by how much is blooming down in Salt Lake City proper as compared to up by my house. The elevation difference is only about 400-500 ft, but spring in downtown is in full swing with forsythia, tulips, daffodils, and various red, white or purple tree blossoms. Up by my house (4,800 feet), we’re just starting to see bits of color: I snapped this forsythia bush about a block from my house on the way home last night.

Yet another side note: The globe willows are now at their spectacular lime-green color peak in the valley. Here’s the group I photographed 3 weeks ago at the apartment complex by my office.

Yet another side note: The globe willows are now at their spectacular lime-green color peak in the valley. Here’s the group I photographed 3 weeks ago at the apartment complex by my office.

Next up: So what’s going on with the dandelions back here in Utah?

So the structure of dandelions is pretty cool. But the genetics are even cooler.

So the structure of dandelions is pretty cool. But the genetics are even cooler. That’s right, virtually all of the dandelions in your yard and your office park have not 16 but 24 chromosomes, and their ovules don’t need or accept pollen from other dandelions. Instead, they reproduce via a process called apomixis (or technically agamospermy in angiosperms) whereby ovules are created without meiosis, are therefore fully triploid right from the get-go, and set to develop into seeds without fertilization.

That’s right, virtually all of the dandelions in your yard and your office park have not 16 but 24 chromosomes, and their ovules don’t need or accept pollen from other dandelions. Instead, they reproduce via a process called apomixis (or technically agamospermy in angiosperms) whereby ovules are created without meiosis, are therefore fully triploid right from the get-go, and set to develop into seeds without fertilization. But some dandelions are sexual diploids and reproduce according to the standard angiosperm model. But to see this, we should leave

But some dandelions are sexual diploids and reproduce according to the standard angiosperm model. But to see this, we should leave  T. officianale in Central and

T. officianale in Central and  Side note: The triploid T. officianale- particularly those that don’t manufacture significant pollen- seem to realize a productivity benefit: they produce more seeds than their diploid brethren.

Side note: The triploid T. officianale- particularly those that don’t manufacture significant pollen- seem to realize a productivity benefit: they produce more seeds than their diploid brethren.

All dandelions are female? They’ve given up on sex? Every dandelion is a clone?

ReplyDeleteEric- almost, but not quite. First, Dandelions are “perfect” or hermaphroditic flowers, meaning that they’re both male and female. Second, every Dandelion you’re likely to see in the US is a clone, but not the *same* clone. There are several dozen distinct triploid lines in the US, the results of different introductions from Europe, as well as possibly the formation of new triploid lines through the sexual reproduction of a triploid “import” and a diploid (sexually-reproducing) native. (There *are* sexually reproducing Dandelions here, as I detailed in the next post; you’re just not very likely to come across them.)

ReplyDeleteThird, it’s only partly the case that they (the triploid clones) have “given up on sex”, because many still produce viable pollen, and are therefore capable of crossing with diploid Dandelions (should they encounter them) creating new, non-clonal, triploid offspring (which might then go on to found *new* clonal lines of their own.) So while the triploids may have “given up” on sex from a female perspective, they haven’t given up on it from a male persective, which was the reason for my “hedging its bets” comment.

Hope this helps!

So for the triploids to keep producing pollen (over evolutionary time that is) there must be a steady stock of diploids around.. why bother to inves the energy in pollen otherwise? There must be some benefit to being a 'sexy dandelion' to survive in a world of fast-reproducing cloning dandelions. Or do the triploids create haploid pollen along with diploid pollen?

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteI would venture to guess that the triploids occasionally produce diploids spontaneously, but that the diploids generally can't keep up with the faster reproduction of the triploids. Enough genetic testing for lineages will tell in time, but to me it makes sense in many ways. If I'm right, then an initially all triploid population should eventually have some rare diploids to make with, allowing the mixing of genetics among the small diploid population, which would then provide plenty of new diversity for the triploids to mate with. It's a bit of a two gender scheme, where the triploid gender mainly asexually reproduces but also mates with the diploid gender, wich in turn can mate with either gender. If most plants and animals, it would probably be fatal to an offspring to have triploid chromosomes, but obviously in the dandelion it is not, nor is it fatal to have diploid chromosomes, so my guess is that the switch can happen either way and is rare enough to not be readily observed, but that in dandelions evolution has worked out survival traits in both cases and a reasonable compromise between the relative stability of asexual reproduction and the relative instability of sexual reproduction. Such a compromise can of course also evolve over time and be effected by selection. I'm sure lawn mowers are a factor there. :)

ReplyDeleteI found a dandelion in my yard that has 6 flowers onone thick stem. There are 2 of these, symmetric about the center, and lots of plain old one-headed ones. Ever heard of this?

ReplyDeleteThat's called fasciation.

ReplyDelete