It’s hot, hot, hot. No rain in the forecast. The valley air has a whitish, unhealthy-looking haze, and all I want to do is zip up one of the canyons and hike or bike in the shade of aspen and fir. But before I do, there’s one more foothill tree, which I’ve been mentioning here and there ever since my very first post. And though it may seem scrubby and unassuming, it’s worth checking out and thinking about, not just for what it is, but what it hints at how the world might have turned out.

It’s hot, hot, hot. No rain in the forecast. The valley air has a whitish, unhealthy-looking haze, and all I want to do is zip up one of the canyons and hike or bike in the shade of aspen and fir. But before I do, there’s one more foothill tree, which I’ve been mentioning here and there ever since my very first post. And though it may seem scrubby and unassuming, it’s worth checking out and thinking about, not just for what it is, but what it hints at how the world might have turned out. A Whole Bunch Of Info Before I Get To The Point

I was in Utah a full year before I noticed Curlleaf Mountain Mahogany, Cercocarpus ledifolius. I was climbing up the ultra-steep, ultra-exposed Grove Creek trail down in Pleasant Grove during a Winter thaw, and I thought how odd it was that these trees lining the trail should have green leaves in February.  Since then I’ve run into Curlleaf Mountain Mahogany (CMM) all over the Wasatch- in Upper Mill Creek Canyon, on the high slopes of Wire Peak, capping Alex Peak up in Pinebrook. In the foothills, it’s the only green thing for most of the winter (with the sparse exception of Juniper.) When it occurs alongside Juniper, it can be easily distinguished even from a great distance by its lighter, almost olive tone.

Since then I’ve run into Curlleaf Mountain Mahogany (CMM) all over the Wasatch- in Upper Mill Creek Canyon, on the high slopes of Wire Peak, capping Alex Peak up in Pinebrook. In the foothills, it’s the only green thing for most of the winter (with the sparse exception of Juniper.) When it occurs alongside Juniper, it can be easily distinguished even from a great distance by its lighter, almost olive tone.

Tangent: The trees that remind me most of CMM are olive trees. Several years ago my wife and I drove across Spain through endless hills of olive trees, and it was like driving through an endless, rolling CMM woodland.

Quick Clarification: “Mountain Mahogany” is not at all closely related to “Mahogany”. True Mahogany trees are of the genus Swietenia, native to Central America and the West Indies, and today commonly grown on plantations in places like India. The term “Mountain Mahogany” was coined by settlers probably in light of the density of the wood, the only conceivable similarity to Swietenia. This type of mis-naming also occurred with Utah Juniper, which is today still commonly known at “Cedar” by many native Utahns, due to its vaguely cedar-like scaled needles, and perhaps the aromatic smell of its burning wood.

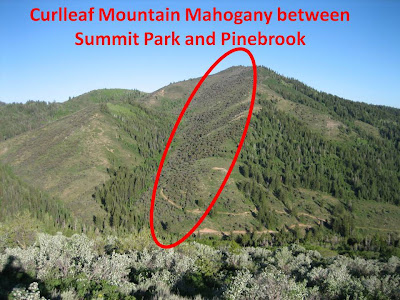

I think of CMM as the “third” foothill tree. Like Gambel Oak and Bigtooth Maple it’s wind-pollinated, constitutes important browse for deer and various other foothill critters, and largely disappears around 7,500-8,000 feet. But if Oak and Maple are the “A” and “B” players, then CMM is the distant “C” in the Wasatch. It grows almost exclusively in treacherous footholds on rocky ridges and exposed gravelly slopes, seemingly pushed to the margins by its more successful companions. They often appear in ones or twos, but sometimes in larger stands, such as the one capping Alex Peak, or these south-facing slopes at around 7,500 feet between Pinebrook and Summit Park.

I think of CMM as the “third” foothill tree. Like Gambel Oak and Bigtooth Maple it’s wind-pollinated, constitutes important browse for deer and various other foothill critters, and largely disappears around 7,500-8,000 feet. But if Oak and Maple are the “A” and “B” players, then CMM is the distant “C” in the Wasatch. It grows almost exclusively in treacherous footholds on rocky ridges and exposed gravelly slopes, seemingly pushed to the margins by its more successful companions. They often appear in ones or twos, but sometimes in larger stands, such as the one capping Alex Peak, or these south-facing slopes at around 7,500 feet between Pinebrook and Summit Park.

At the end of May, CMM flowers appear. The flowers are perfect, petal-less, and like most wind-pollinated flowers, pretty unassuming. After pollination, the plant produces achenes with long, plume-like tails.

At the end of May, CMM flowers appear. The flowers are perfect, petal-less, and like most wind-pollinated flowers, pretty unassuming. After pollination, the plant produces achenes with long, plume-like tails.

Tangent: “Achene” is one of those botanical terms I skipped over earlier in the season, but have found it’s such a common thing it’s worth defining. An achene in a dried fruit that encloses and nourishes a single seed. Achenes are typically small, and often wind-borne away from the mother-plant with the help of a parachute of plume formed by the dried and extended calyx of the original flower, such as we’ve seen in Dandelions, Musk Thistle and Heartleaf Arnica.

Tangent: “Achene” is one of those botanical terms I skipped over earlier in the season, but have found it’s such a common thing it’s worth defining. An achene in a dried fruit that encloses and nourishes a single seed. Achenes are typically small, and often wind-borne away from the mother-plant with the help of a parachute of plume formed by the dried and extended calyx of the original flower, such as we’ve seen in Dandelions, Musk Thistle and Heartleaf Arnica.

The achene-plumes of CMM are highly distinctive, appear in late June, and give the whole tree a whitish, almost hazy, ephemeral appearance until you get right close up.

Tangent: This “hazy” effect often gives me the impression that the trees are “out-of-focus”, especially when I’m passing them quickly on a mountain bike. This time of year, the sense that some tree/shrub is out-of-focus in the periphery of my vision is usually the first alert that I’m passing CMM.

Tangent: This “hazy” effect often gives me the impression that the trees are “out-of-focus”, especially when I’m passing them quickly on a mountain bike. This time of year, the sense that some tree/shrub is out-of-focus in the periphery of my vision is usually the first alert that I’m passing CMM.

CMM grows slowly; trees take ~100 years to grow to full height (which is only 20- 30 feet max) and can live for over a thousand years. The wood is brittle and extremely dense: CMM wood sinks in water.

Tangent: I don’t know if it sinks in salt water. One of my half-baked “experiment” ideas is to get a chunk of CMM wood and take it to the Great Salt Lake to find out. This sounds easy enough, but most of the time that I come across a dismembered CMM limb I’m far enough from a trailhead that I’m not up for carrying the ridiculously heavy piece of wood back to the car…

The Point

OK, so what? So CMM is a slow-growing, scrubby, arid-climate tree without dazzling flowers or foliage. Why blog about it? Here’s why: it’s an evergreen angiosperm, in the Intermountain West, occurring here at latitude 40 degrees North, and in fact way up into Montana, around 50 degrees North. Think about that for a minute.  The closest other evergreen angiosperm “tree” is Shrub Live Oak, Quercus Turbinella, at least 250 miles South of Salt Lake, and only under the most extreme circumstances and generous definition could it ever be called a “tree”. The next closest contender would be the Joshua Tree, also pushing it for a “real” tree, and a monocot to boot. The closest “real” dicot evergreen angiosperms would be live oaks, which you don’t get till the far side of the Sierras going West, or the South side of the Mogollon Rim (well into Arizona) going South.

The closest other evergreen angiosperm “tree” is Shrub Live Oak, Quercus Turbinella, at least 250 miles South of Salt Lake, and only under the most extreme circumstances and generous definition could it ever be called a “tree”. The next closest contender would be the Joshua Tree, also pushing it for a “real” tree, and a monocot to boot. The closest “real” dicot evergreen angiosperms would be live oaks, which you don’t get till the far side of the Sierras going West, or the South side of the Mogollon Rim (well into Arizona) going South.

In this light, CMM is remarkable. Its small tough, waxy leaves hang on throughout the winter (It uses the Blackbrush strategy of a thick waxy coating vs. the Sagebrush hairy leaf strategy) when every other “real” angiosperm tree within 500 miles is standing bare. Evergreen angiosperms belong in the tropics, in the jungle, not in the middle of the Great Basin. But here CMM is, living and thriving through our wind-swept, icy winters with a completely different way of tackling the winter/leafing problem than any other tree around. It’s a bizarre, unique, wonderful anomaly, totally unlike any other tree around.

Tangent: I get a weird sense of comfort and optimism from CMM. I love the idea that success in life isn’t necessarily bound to a single path or a unique formula. That there are different ways to survive and thrive and propagate are a large part of what fascinates me about the plant world, and I’d like to think that at some level, the same is true in the human world.

The CMM story in itself is worth appreciating, but it wasn’t until last Fall, when I stumbled across another species of Cercocarpus, that I fully appreciated the significance and possibility of Mountain Mahogany.

Next up: The other Mountain Mahogany

Thank you so much for blogging the Mountain Mahogany. I just got back from a trip to Mount Charleston outside Las Vegas and the beautiful trees up there hypnotized and energized me. I cannot wait to go back up there and bribe some local to part with half a cord. I will bring it back down to the valley and turn the firewood into beautiful furniture if I have my druthers. Such a dense wood will surely dull my sawblades, but how can one pass up such an opportunity?! The beauty of nature is sublime and enduring. The rocks up there--the faces, the loose stones--are also very comforting: proof of continuity and the immortality of nature.

ReplyDeleteWhere in Utah can I find the most oregon grape, raspberries, and currant bushes? Any ideas?

ReplyDeleteKimball- Oregon Grape is everywhere in the foothills, common ground cover wherever the scrub oak is higher than your head. It's easy to find now because it's some of the only green leafy stuff (though some of the leaves are more red than green now.) An easy spot is City Creek trailhead of Bonneville Shoreline trail. Go either way, you'll see some within 5 minutes walking.

ReplyDeleteDon't have a raspberry spot- did you mean thimbleberries? Easiest spot is Big Water trail in Mill Creek Canyon (summer only) from lower trailhead. Walk ~3 minutes past first switchback, start looking on the right/uphill side.

Wax currant is common but I don't have an obvious easy place to send you. It's common around/near rocky overlooks around 7,000 - 7,500 feet in the Wasatch.

Awesome, thanks for the heads' up.

ReplyDeleteBJ Hamaker,

ReplyDeleteDid you ever get yourself a sample of mountain mahogany to work with? I've been looking for some also - just a little for fun, nothing commercial. But finding a patch, getting your hands on it, back down to your house, etc. is more complicated than I thought. Let me know if you get some. I've got a nice bandsaw and carbide-toothed blade that can make some nice boards our of it.