If you’re collecting acorns, this is the time to get out in the foothills and pick them. And that might be a good idea if you are: a) a Jay, or b) a Squirrel, or c) a Person Who Knows How To Make Something Edible Out Of Acorns.

If you’re collecting acorns, this is the time to get out in the foothills and pick them. And that might be a good idea if you are: a) a Jay, or b) a Squirrel, or c) a Person Who Knows How To Make Something Edible Out Of Acorns.

For the past couple of years, I’ve really wanted to be C, but I’m thinking it isn’t going to happen. And that’s a disappointment for 2 reasons, neither of them very practical.

First, I always like to think that in a pinch, if civilization broke down or something, I could live off the land. This is of course total BS. I don’t hunt, I’m a neophyte fisherman, and a lame forager. Earlier this year I blogged about my abject failure to dig up an edible Glacier Lily corm, and with the exception of Ballhead Waterleaf salad & roots, I’m hard-pressed to think of something real edible I’ve come across this year in the Wasatch. The one “edible” thing I come across in huge quantities every year right around now is acorns. And I like to think that if I went out into the foothills for a few days and filled several snacks, I could somehow get by through the year on a variety of acorn-based concoctions.

First, I always like to think that in a pinch, if civilization broke down or something, I could live off the land. This is of course total BS. I don’t hunt, I’m a neophyte fisherman, and a lame forager. Earlier this year I blogged about my abject failure to dig up an edible Glacier Lily corm, and with the exception of Ballhead Waterleaf salad & roots, I’m hard-pressed to think of something real edible I’ve come across this year in the Wasatch. The one “edible” thing I come across in huge quantities every year right around now is acorns. And I like to think that if I went out into the foothills for a few days and filled several snacks, I could somehow get by through the year on a variety of acorn-based concoctions.

The second reason is even wackier. Lots of people know that American Indians ate acorns in various forms- soups, breads, meal. But what most people don’t know is that acorns fueled some of the most advanced, populous, and arguably successful pre-agricultural societies in history, in coastal California.

The second reason is even wackier. Lots of people know that American Indians ate acorns in various forms- soups, breads, meal. But what most people don’t know is that acorns fueled some of the most advanced, populous, and arguably successful pre-agricultural societies in history, in coastal California.

Detour Full of Acorn Info Before I Get to the Point

This season we’ve looked at a bunch of different plant reproductive strategies. Oak is what I call a “Wind-Agent” plant: wind-pollinated, agent-dispersed. The agents are all sorts of critters, but most notable Jays and squirrels. We’ve talked about Jays already, and I’ll talk about squirrels when I blog about Fir cones. But the strategy works because critters collect more acorns than they can eat anytime soon, and save/hide/cache them for later. They usually never recover all of the acorns they cache, and that gives a few acorns a chance to seed into new oaks.

Lots of plants use a similar “Wind-Agent” strategy, and lots of seeds are cached by critters. But what makes Oaks notable is the size and richness of their seeds. An acorn is a big investment for a plant, and a huge score for a critter, and so I characterize it as a “Big-Hand” seed strategy, as in, “I’m going to place fewer bets, but I’m going to make them big bets, and give each bet the best chance of winning.” This is opposed to the Maple strategy of, “I’m going to buy every scratch ticket at every Kum & Go in Wyoming and hope one of ‘em hits the jackpot.”

Lots of plants use a similar “Wind-Agent” strategy, and lots of seeds are cached by critters. But what makes Oaks notable is the size and richness of their seeds. An acorn is a big investment for a plant, and a huge score for a critter, and so I characterize it as a “Big-Hand” seed strategy, as in, “I’m going to place fewer bets, but I’m going to make them big bets, and give each bet the best chance of winning.” This is opposed to the Maple strategy of, “I’m going to buy every scratch ticket at every Kum & Go in Wyoming and hope one of ‘em hits the jackpot.”

Tangent: Despite my rather tortured use of gaming analogies, I don’t gamble. It’s not a big moral objection or anything; I just don’t get it. That is, I do understand how it works and all, but I’ve never managed to experience the pleasure that so many others apparently do while indulging. In this respect, it’s one of a fairly broad array of activities- like playing golf or watching spectator sports- that, while wildly popular with people in general- presents me with no interest or enjoyment. When it strikes, this feeling of “missing it” or “disconnection” (which I imagine as somehow akin to what a gay man experiences at a strip club) makes me feel oddly out-of-sync with humanity in general…

Tangent: Despite my rather tortured use of gaming analogies, I don’t gamble. It’s not a big moral objection or anything; I just don’t get it. That is, I do understand how it works and all, but I’ve never managed to experience the pleasure that so many others apparently do while indulging. In this respect, it’s one of a fairly broad array of activities- like playing golf or watching spectator sports- that, while wildly popular with people in general- presents me with no interest or enjoyment. When it strikes, this feeling of “missing it” or “disconnection” (which I imagine as somehow akin to what a gay man experiences at a strip club) makes me feel oddly out-of-sync with humanity in general…

If you’re the size of a squirrel, an acorn is about the size of a cantaloupe, and they’re chock full of proteins, carbohydrates and fats, as well as calcium, phosphorus and potassium. They’ve co-evolved with Jays and Squirrels for millions of years, and fact that they produce a bumper crop once a year or once every other year forces critters to cache them, which over course is the whole point from the Oak’s point of view.

If you’re the size of a squirrel, an acorn is about the size of a cantaloupe, and they’re chock full of proteins, carbohydrates and fats, as well as calcium, phosphorus and potassium. They’ve co-evolved with Jays and Squirrels for millions of years, and fact that they produce a bumper crop once a year or once every other year forces critters to cache them, which over course is the whole point from the Oak’s point of view.

People too can and have benefitted from acorns, but to do so have to deal with the tannins.

What Are Tannins?

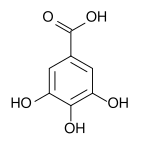

I’ve referred to tannins (sample molecular diagram right) before, most recently when talking about leaf color, and it seems people who are big on wine-tasting are always talking about tannins as well. Tannins are a class of chemicals produced by plants that act as astringents. An astringent is a chemical that constricts organic tissues by binding or shrinking proteins in living things. This shrinkage causes a puckering sensation on the mouth and tongue, which is why acorns and red wine both taste a bit bitter (though to far different degrees…)

I’ve referred to tannins (sample molecular diagram right) before, most recently when talking about leaf color, and it seems people who are big on wine-tasting are always talking about tannins as well. Tannins are a class of chemicals produced by plants that act as astringents. An astringent is a chemical that constricts organic tissues by binding or shrinking proteins in living things. This shrinkage causes a puckering sensation on the mouth and tongue, which is why acorns and red wine both taste a bit bitter (though to far different degrees…)

Excessive tannins can cause liver damage, so to make a regular diet of acorns, the tannins must be removed, or leached, from the acorns prior to consumption. The common way is immersing them in running water for a period of time, or boiling.

So How Do Animals Deal With Tannins?

This turns out to be way interesting. First off, it’s not clear whether birds can taste astringency. With mammals, it seems to be a bit more complicated. They can and do select for lower-tannin acorns. As a rule, acorns from “white oaks” (section = Quercus) have lower tannin concentrations than acorns from “red oaks” (section = Erythrobalanus) (What’s the difference between a “section” and a “subgenus”? Beats me. They both seem to be terms for grouping of species with a given genus…)

Tangent: I haven’t talked about White vs. Red oaks previously, because the 2 native oaks we’ve looked at here in Utah- Gambel Oak and Shrub Live Oak- are both White Oaks. But I’ve encountered 2 Red Oaks in my travels this summer, though didn’t get a chance to blog about them. I saw California Black Oak, Quercus kellogii, (pic right) when tromping around in the mountains East of San Diego back in June, and

Tangent: I haven’t talked about White vs. Red oaks previously, because the 2 native oaks we’ve looked at here in Utah- Gambel Oak and Shrub Live Oak- are both White Oaks. But I’ve encountered 2 Red Oaks in my travels this summer, though didn’t get a chance to blog about them. I saw California Black Oak, Quercus kellogii, (pic right) when tromping around in the mountains East of San Diego back in June, and  Northern Red Oak, Quercus rubra, (leaf pic left) galore while vacationing in New England in July. Another difference between White and Red Oaks is that White Oaks produce acorns every year, while Red Oaks grow them every other year. Red Oaks are native only to the New World, while White Oaks are native to both Old World and New.

Northern Red Oak, Quercus rubra, (leaf pic left) galore while vacationing in New England in July. Another difference between White and Red Oaks is that White Oaks produce acorns every year, while Red Oaks grow them every other year. Red Oaks are native only to the New World, while White Oaks are native to both Old World and New.

White and Red Oaks don’t hybridize naturally, but Cottam was able to produce a number of White-Red hybrids in his research, and in fact Cottam Grove at Red Butte Garden contains a beautiful Q. gambelii x kellogii hybrid (leaves pic right.)

White and Red Oaks don’t hybridize naturally, but Cottam was able to produce a number of White-Red hybrids in his research, and in fact Cottam Grove at Red Butte Garden contains a beautiful Q. gambelii x kellogii hybrid (leaves pic right.)

Second, many critters seem better to able to tolerate tannins than humans, and others effectively dilute the tannins by eating the acorns in combination with other, non-tannic foods. But caching can also help; over time groundwater can help leach tannins from cached acorns.

Tangent: For me this suggests a fascinating evolutionary teaser- did oaks evolve tannin-rich acorns to force caching?

Where I Get Back To The Point

So yeah, the thing with the Indians, and the second reason. So, like a lot of wannabe-back-to-nature suburban enviro-types, I have mixed feelings about agriculture.  I love going to the supermarket and buying fresh avocados year-round and all, but I can’t help but wonder if the widespread adoption of agriculture was in some ways a bad thing. Cities, nations, wars, epidemics, large-scale environmental destruction, and rigid, despotic hierarchical social structures- all were really made possible by agriculture. But on the other hand, living out in the woods with no comforts of civilization in a small group hunting rabbits and digging up roots all day sounds like a drag too… And this is where the coastal Indians come in. These guys created large, complex, rich, thriving societies- without agriculture. They did it in large part because of the resource rich area in which they dwelt, which included such calorie-rich hunted and gathered food-stuffs such as fish, shellfish, and – you guessed it- acorns. California is wildly rich in Oaks and used to be even more so, before the widespread destruction of woodlands for agriculture.

I love going to the supermarket and buying fresh avocados year-round and all, but I can’t help but wonder if the widespread adoption of agriculture was in some ways a bad thing. Cities, nations, wars, epidemics, large-scale environmental destruction, and rigid, despotic hierarchical social structures- all were really made possible by agriculture. But on the other hand, living out in the woods with no comforts of civilization in a small group hunting rabbits and digging up roots all day sounds like a drag too… And this is where the coastal Indians come in. These guys created large, complex, rich, thriving societies- without agriculture. They did it in large part because of the resource rich area in which they dwelt, which included such calorie-rich hunted and gathered food-stuffs such as fish, shellfish, and – you guessed it- acorns. California is wildly rich in Oaks and used to be even more so, before the widespread destruction of woodlands for agriculture.

And so acorns represent for me not just a fun experiment, but a connection to a lost world- the long-gone acorn-oriented gatherer societies of pre-contact coastal California- and a tiny “taste” of how human society might possibly have turned out, in an alternative, gatherer-based world.

Unfortunately, my forays into acorns-cuisine have bumped up against a harsh reality: Acorns kind of suck to eat.

Back in April, when I was on my Glacier-Lily-Corm-Jihad, I mentioned how I’d previously tried boiling and eating acorns. I repeated the experiment this week, with equally dismal results, confirmed by my assistant tasters, Bird Whisperer and Twin B. (Twin A has a nut allergy, and was thus exempted from tasting duty…)

So I tried a Plan B: Acorn Jelly. This is a gelatinous substance made out of acorns, commonly eaten in Korea, where it is known as “Dotorimuk”. In the book Oak- The Frame of Civilization the author, William Bryant Logan, describes eating acorn jelly as a break-through nutritional and gastronomic experience. So I thought great, I can just get me some of this jelly and do the big karmic acorn-connection thing while bypassing the whole “leaching” dick-dance… I called around and found dotorimuk at a local Asian market

So I tried a Plan B: Acorn Jelly. This is a gelatinous substance made out of acorns, commonly eaten in Korea, where it is known as “Dotorimuk”. In the book Oak- The Frame of Civilization the author, William Bryant Logan, describes eating acorn jelly as a break-through nutritional and gastronomic experience. So I thought great, I can just get me some of this jelly and do the big karmic acorn-connection thing while bypassing the whole “leaching” dick-dance… I called around and found dotorimuk at a local Asian market

The Video!

At home, I recruited my most reliable food-tester, Wonder Boy aka The Bird Whisperer, and filmed the taste-test in this exciting Culinary Action Video:

I followed with my own tasting. It’s repulsive, with the consistency of a super-soft tofu, but with a vaguely biotic-yet-dully-bitter taste. I couldn’t yet bring myself to throw it out, and hope to rally myself to ingest another slice or two this weekend, before calling the “experiment” complete…

I followed with my own tasting. It’s repulsive, with the consistency of a super-soft tofu, but with a vaguely biotic-yet-dully-bitter taste. I couldn’t yet bring myself to throw it out, and hope to rally myself to ingest another slice or two this weekend, before calling the “experiment” complete…

OK. I’m done with the foraging thing. Back to Albertson’s.

Great post! I am also interested in the indigenous diets of North American before contact with Europeans. I feel the same way about the convenience and taste of our modern food chain but it's impacts on humanity and the environment aren't too great either.

ReplyDeleteAnyway thanks for sharing!

Good evening from the island of Kea in Greece. It's great to meet a fellow acorn appreciator. I have baked many successful muffins, bread, pie crusts and cookies with acorn meal and acorn flour. I invite you to read the very brief overview of a new acorn initiative that I am launching on Kea at www.redtractorfarm.com/acorns.html

ReplyDeleteThanks for the excellent post!

Best wishes,

Marcie Mayer Maroulis