OK, so no now that we know all about inversions, back to the biking part. The ride I had my eye on all last week for Saturday didn’t pan out. I had hopes of doing the Cedar Mountain loop, but around Thursday realized that the melt wasn’t happening fast enough. So I changed plans and rode Stansbury Island, then zipped out to the Aragonite exit off I-80 and did a quick out & back to the top of Hastings Pass.

OK, so no now that we know all about inversions, back to the biking part. The ride I had my eye on all last week for Saturday didn’t pan out. I had hopes of doing the Cedar Mountain loop, but around Thursday realized that the melt wasn’t happening fast enough. So I changed plans and rode Stansbury Island, then zipped out to the Aragonite exit off I-80 and did a quick out & back to the top of Hastings Pass.

But I’ve done the whole Cedar Mountain Loop a couple of times before, and it’s one of my favorite inversion rides. The Cedar Mountains are the 3rd range West of Salt Lake Valley, and the last range before the Salt Flats and Nevada. They’re a low range, topping out at about ~7,700 feet. The loop isn’t really a “mountain bike ride”, so much as it is a road ride you do on a mountain bike. The 56 mile loop follows graded dirt roads up over the range via Hastings Pass, then follows the East side of the range down to Rydalch Pass, where it crosses to the West side and then heads North back up to the start.

I’ve ridden it before during an inversion, and it made for a fascinating meteorological show & tell. The long stretches down the East flank and back up the West side were full-on winter, riding bundled up, with temps in the mid-20’sF. But the two passes were bright, sunny and spring-like, pushing 40F.

I’ve ridden it before during an inversion, and it made for a fascinating meteorological show & tell. The long stretches down the East flank and back up the West side were full-on winter, riding bundled up, with temps in the mid-20’sF. But the two passes were bright, sunny and spring-like, pushing 40F.

Practically speaking, this is the kind of ride worth doing maybe once a year, when there are no other good riding options, you have a free day, and you want to spend it out in the middle of nowhere. So it usually gets ridden (if at all) on clear winter or early spring days. But this is the dangerous part; the soils and roads are clay, and if there’s still moisture in the soil- from snow or frost- and the temps climb above freezing while you’re out there, you’re stuck. You cannot turn a wheel in this mud, and if you get stuck you’re looking at a long wait- probably till 10PM or so, when the mud re-freezes.

WARNING: Don’t attempt either of these rides now, unless your timing allows you to do the whole ride while it’s frozen.

So at dawn I was climbing up the frozen Stansbury Island trail, which though not as remote as the Cedar Mountains, is singletrack that follows the old Lake Bonneville shoreline at about 5,000 feet, right along the top of the inversion layer. I got back to the truck before 10AM, and things were still frozen, so I headed further West, out to the Cedars, thinking to get a quick climb free and clear above the inversion.

So at dawn I was climbing up the frozen Stansbury Island trail, which though not as remote as the Cedar Mountains, is singletrack that follows the old Lake Bonneville shoreline at about 5,000 feet, right along the top of the inversion layer. I got back to the truck before 10AM, and things were still frozen, so I headed further West, out to the Cedars, thinking to get a quick climb free and clear above the inversion.

Tangent: Here’s another cool thing to do on Stansbury Island that almost no one ever does: Hike. Not the trail- that’s boring. Go for the peaks instead. When you drive onto the island toward the bike trail head, park your car either at the T/H, or at the junction of the main West-side road and the T/H access road. Walk up the main West-side road about another mile, and there’ll be a road veering off 45 degrees to the right/Northeast. Follow it for a couple hundred yards; it ends in a dirt lot. Climb the hill in front of you and start working your way up the side ridge to the main ridge. Once on the main ridge, work your way North the peak. It’s easy.

If the directions don’t make sense, just follow my Standard Great Basin Peak Ascent Methodology, which I described in this post. (Man, it’s like I have a post for everything…)

If the directions don’t make sense, just follow my Standard Great Basin Peak Ascent Methodology, which I described in this post. (Man, it’s like I have a post for everything…)

Climbing the Northern peak, which is lower but looks more dramatic, takes a bit more effort. Getting down into the Juniper woodland between the peaks is easy, but finding your way up the Northern peak involves negotiating a series of cliff-bands that can be a bit hazardous if you’re alone. Anyway, first/ Southern/ highest peak is great and easy, second/ Northern peak a bit more involved.

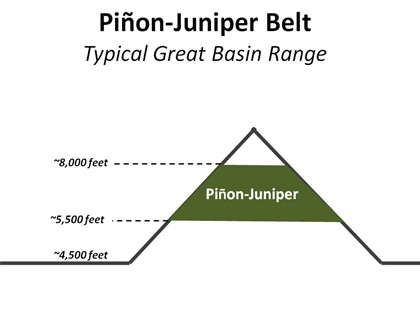

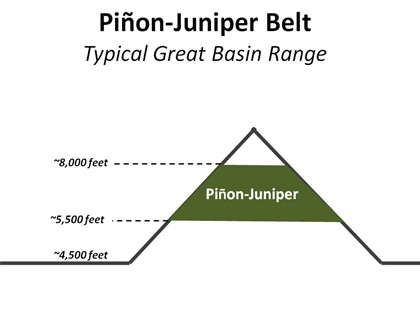

The Cedar range is unspectacular and typical of about 100+ ranges across the Great Basin, in that it doesn’t reach high enough to support real forest, only Juniper woodland. Through the entire range there’s just one tree, Utah Juniper, Juniperus osteosperma, and this same tree is the only tree on Stansbury Island, and the only tree in the nearby Grassy Mountains. It’s the only tree in the Newfoundland Mountains, the only tree in the Lakeside Mountains, and… you get the idea. Utah Juniper tolerates the lowest, driest conditions of any tree in the Great Basin, and that’s why it’s always the first tree you encounter as you climb out of a basin. In many other Great Basin ranges it coexists with Singleleaf Piñon, Pinus monophylla, and together they form Pinon-Juniper Woodland. (For background info on Singleleaf Piñon- a super-cool tree- see the “Botanical Spotlight” in this post.)

The Cedar range is unspectacular and typical of about 100+ ranges across the Great Basin, in that it doesn’t reach high enough to support real forest, only Juniper woodland. Through the entire range there’s just one tree, Utah Juniper, Juniperus osteosperma, and this same tree is the only tree on Stansbury Island, and the only tree in the nearby Grassy Mountains. It’s the only tree in the Newfoundland Mountains, the only tree in the Lakeside Mountains, and… you get the idea. Utah Juniper tolerates the lowest, driest conditions of any tree in the Great Basin, and that’s why it’s always the first tree you encounter as you climb out of a basin. In many other Great Basin ranges it coexists with Singleleaf Piñon, Pinus monophylla, and together they form Pinon-Juniper Woodland. (For background info on Singleleaf Piñon- a super-cool tree- see the “Botanical Spotlight” in this post.)

If you drive across Nevada in I-80 or US50, you’ll see the same thing over and over and over again: flat basin filled with shrubs, then the land starts to rise, then Junipers start to appear. Depending on how high the range/ridge rises, there may then appear Piñons or even other, “real” trees higher up, but when you go back down the other side, the same thing will happen in reverse: eventually the Junipers will peter out, and then not long after, you’ll reach the bottom of the slope and the “floor” of the next basin.

When I first drove across the Great Basin, almost 20 years ago, I assumed the Junipers just didn’t grow on the valley floors because not enough rainfall reached them. But it turns out that their lower distribution is limited by another factor as well: thermal inversions.

When I first drove across the Great Basin, almost 20 years ago, I assumed the Junipers just didn’t grow on the valley floors because not enough rainfall reached them. But it turns out that their lower distribution is limited by another factor as well: thermal inversions.

Along the Wasatch Front, we tend to think of inversions as a local thing, but people who live out in the middle of the Basin, in places like Elko or Austin or Ely (people like this lady) know that inversions happen routinely all over the Great Basin, clear to the Sierra. Across the Basin, Piñon-Juniper woodlands occur on hundreds of ranges. And on almost all of them, the lower limit of Juniper coincides with the upper limit of the winter-time thermal inversions.

Utah Juniper is tough tree. We looked at its wood architecture, and specifically its reinforced xylem, last Spring in the Newfoundland Mountains. It also has other tricks to defend itself against drought and freezing, including small, scale-like needles, and the ability to selectively kill off limbs in times of stress. But the temperature difference between the inversion layer and just above it can often be 10-15F degrees, and this difference seems to spell the limit even for this tough tree.

Utah Juniper is tough tree. We looked at its wood architecture, and specifically its reinforced xylem, last Spring in the Newfoundland Mountains. It also has other tricks to defend itself against drought and freezing, including small, scale-like needles, and the ability to selectively kill off limbs in times of stress. But the temperature difference between the inversion layer and just above it can often be 10-15F degrees, and this difference seems to spell the limit even for this tough tree.

The inversions have influenced life in other ways. Archeologists have found that Paiute encampments almost always stuck to the Piñon-Juniper belt, and rarely find evidence for them in valley bottoms. One good reason for this would be access to the Great Basin’s most predictable, reliable, high fat & carbohydrate food source: Piñon nuts. But when your whole life is basically one long camp-out, in an age before down sleeping bags and gore-tex, a 10-15F gain in wintertime temperature was probably another factor in campsite selection.

The inversions have influenced life in other ways. Archeologists have found that Paiute encampments almost always stuck to the Piñon-Juniper belt, and rarely find evidence for them in valley bottoms. One good reason for this would be access to the Great Basin’s most predictable, reliable, high fat & carbohydrate food source: Piñon nuts. But when your whole life is basically one long camp-out, in an age before down sleeping bags and gore-tex, a 10-15F gain in wintertime temperature was probably another factor in campsite selection.

A little ways North of the Humboldt River (rough path of I-80) the thermal inversion pattern of the central Great Basin is disrupted by storm tracks coming in from the Northwest. These storms aren’t blocked by any “wall” as formidable as the Sierra, and so extended thermal inversions are rare here. And in fact, North of the Humboldt is where the Piñon-Juniper belts effectively end, with Piñon just barely making it to the Idaho line.

Many Great Basin ranges don’t have any trees except Juniper or Piñon and Juniper, and when the ranges reach high enough, this can create an artificially low “timberline” of around 8,000 or so feet, above which is too cold to support Piñon. But interestingly, 8,000 feet is often too low (not enough precip) to support the 3rd-most common Great Basin Conifer- our old friend Limber Pine. So on many ranges, a Limber Pine or Limber Pine/Bristlecone Pine forest will kick in 1,000 or more feet above the Piñon-Juniper “timberline”.

This oddity leads to ranges like the Monitor Range (which we skirted between Austin and Eureka on our Tahoe/Hydrology road trip last summer) which actually has two timberlines: a Piñon-Juniper timberline at ~8,000 feet, and a 2nd, higher, Limber Pine timberline at ~11,000 feet.

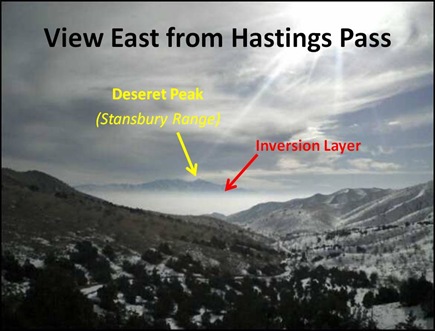

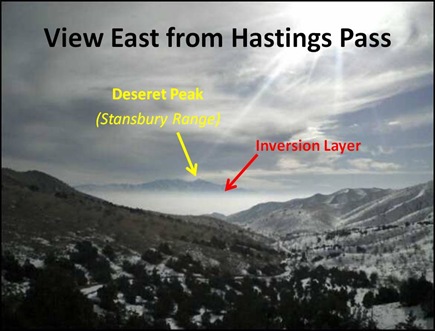

For my second ride- the quickie- I parked at the junction 1.3 miles East of the Aragonite incinerator, at about 4,900 ft. I was still thick in the haze and gloom (pic left.) I unloaded the bike and started pedaling East and up, following the road towards Hastings Pass. After about a mile, the haze started to thin, the world began to get lighter, and as if on cue, Junipers started to appear on either side of the road. I followed the road for another couple hundred yards up into the mouth of a canyon, around a bend, and as I did so the haze lifted completely and I broke out of the inversion.

For my second ride- the quickie- I parked at the junction 1.3 miles East of the Aragonite incinerator, at about 4,900 ft. I was still thick in the haze and gloom (pic left.) I unloaded the bike and started pedaling East and up, following the road towards Hastings Pass. After about a mile, the haze started to thin, the world began to get lighter, and as if on cue, Junipers started to appear on either side of the road. I followed the road for another couple hundred yards up into the mouth of a canyon, around a bend, and as I did so the haze lifted completely and I broke out of the inversion.

Breaking out of an inversion is a joy no matter how you do it- car, airplane, whatever. But to break out of an inversion under your own power, while breathing hard, is one of the sweetest pleasures of a Great Basin Winter. The very air around you changes, and over the course of a couple of minutes, the world becomes brighter and clearer, and a deep chill you’d forgotten was all around and through you is suddenly removed, like a weight lifting. Your lungs quickly feel deeper, clearer and stronger. Your vision seems sharper, crisper than you ever imagined it could or even should be. It’s like entering another world, or even becoming another person.

Breaking out of an inversion is a joy no matter how you do it- car, airplane, whatever. But to break out of an inversion under your own power, while breathing hard, is one of the sweetest pleasures of a Great Basin Winter. The very air around you changes, and over the course of a couple of minutes, the world becomes brighter and clearer, and a deep chill you’d forgotten was all around and through you is suddenly removed, like a weight lifting. Your lungs quickly feel deeper, clearer and stronger. Your vision seems sharper, crisper than you ever imagined it could or even should be. It’s like entering another world, or even becoming another person.

At the pass I lingered longer than I should have, loath to abandon the clarity, sunshine and warmth for another week of hazy gloom. But eventually the math of distance, mph and a committed time of return intruded on my reverie, and I turned the bike around and began the descent back toward Aragonite.

At the pass I lingered longer than I should have, loath to abandon the clarity, sunshine and warmth for another week of hazy gloom. But eventually the math of distance, mph and a committed time of return intruded on my reverie, and I turned the bike around and began the descent back toward Aragonite.

Descending fast into an inversion never ceases to startle and even intimidate me. You know what’s coming- the murky haze, the lower temps. But somehow I’m just never ready for the sheer impact of an inversion chill at 30mph. It immediately envelopes, penetrates, and almost grabs a hold of the very frame of your body. It’s a grip that can’t be blocked or shaken or ignored. It simply has to be endured, until the next brief escape, or eventual, long-awaited storm front.

Descending fast into an inversion never ceases to startle and even intimidate me. You know what’s coming- the murky haze, the lower temps. But somehow I’m just never ready for the sheer impact of an inversion chill at 30mph. It immediately envelopes, penetrates, and almost grabs a hold of the very frame of your body. It’s a grip that can’t be blocked or shaken or ignored. It simply has to be endured, until the next brief escape, or eventual, long-awaited storm front.

Thanks for the link. I remember one year when we had a huge inversion that kept creeping higher and higher on the mountain each day for a week. When I went up above it and looked out at the cloud-covered valleys, it made me imagine the Lake Bonneville days, when instead of clouds, it would have been water filling the valley bottoms.

ReplyDeleteI enjoyed reading about inversions, MTB and hiking routes, pinions, well, everything.

ReplyDeleteI need a long bike ride, preferable out of the gunky air.