Note: I’m away and offline this week. I’ve set up an auto-post series of this Mexican-Tree-Adventure story in my absence.

So it was that one Thursday afternoon in February 2006 I was speeding across the high plateaus of Northern Jalisco in a rental car, racing the sun to the Zacatecas border.

He knew exactly what I was talking about. “Yes, I know the owners of the land”, he said. I hesitated, surprised. He repeated, “I know the owners”, this time in English. I said, sticking to Spanish, “Do you think I should ask them permission to go see the trees?”

“It might be a good idea”, he replied, again in English. “If you like, I can take you there to meet them and ask them while we wait for this guy to get back.”

At this point I switched to English, agreed and together we headed back toward Juchipila in my rental car. My guide introduced himself as Jorge. Jorge had worked for more than 10 years in the U.S. and meeting him was to be my first experience in one of Juchipila’s biggest surprises: the average male over 30 in Juchipila has worked in the US and speaks much better English than I do Spanish.

We drove back into downtown, and Jorge guided me through a confusing maze of one-way streets. We stopped at a driveway through a small gate in the row of what I could best describe as “townhouses”, though it was really just a typical block of Mexican residential homes without any space in between, each sharing a wall with its neighbors. We stepped through the gate and into the small driveway/courtyard of what appeared to be a typical middle-class home. There were a few chairs about, and some piles of things and containers and tools and a few buckets that appeared to indicate various projects underway, though I’d spent enough time in Mexico to recognize that often times such a “project underway” appearance that one might consider temporary in the U.S. is sometimes a bit more permanent in Mexico.

Jorge greeted a man and a woman in the courtyard. The woman was in her mid-30’s, holding a sleeping blonde-haired toddler. (Like so many Americans, I’m always embarrassed to find myself surprised at seeing a blond Mexican. Juchipila was full of Mexicans who appeared “white”.) The man, also in his mid-30’s, was shirtless and shoeless, clad only in sweatpants, and holding some sort of bandage-like wad of gauze to his left armpit.

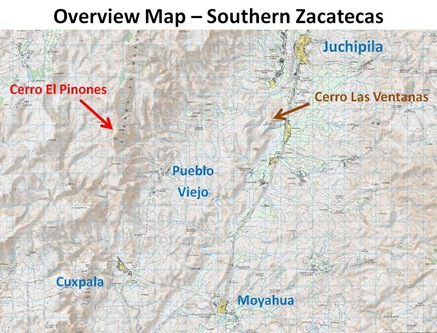

Jorge quickly told the man and the woman, without introductions, why we were there. The exchange was too fast for me to follow completely, but quickly became clear that we needed to speak with another person- apparently the man of the house- who was not there, and was in fact on his way back from Cerro Piñones. The woman recommended we see someone else down the street.

Jorge thanked them and we left, Jorge explaining that there were several residents who owned parts of Cerro Piñones, and that they’d recommended we speak with another in the meantime, who lived only two blocks away. “This guy speaks really good English”, he said. We knocked on a non-descript red door, and were greeted by a teenager. Jorge asked if his father were home and he lead us inside. The room we entered was large, high-ceilinged, and at the far end, in front of a desk with a computer, sat a man and a woman in office-roller chairs. Above the desk, covering that one wall, were about a dozen heavy-metal posters. The man who arose from the desk and computer to greet us appeared to be in his mid-to-late 50’s, and wore his long, graying hair in a ponytail. We introduced ourselves to each other in Spanish and then switched to English, which he spoke fluently with only the slightest trace of an accent. His name was Miguel Lara. Miguel quickly peppered me with questions: Where are you from? What was your name again? Why do you want to see the trees? Who are you with?

I quickly explained that I wasn’t “with” anybody, wasn’t employed by any organization or agency that had anything to do with pines or plants or the natural world in general, but that I was just an “amateur botanist” who had read of the Martinez Piñon and wanted to see it in the wild. Actually, “amateur botanist” was a bit of a stretch, but I was afraid that “ordinary guy who became obsessed with a tree and traveled a couple thousand miles to see it” might sound just a bit too loco-gringo…

Miguel seemed satisfied that I was what I said I was, explained that he was helping the woman at the desk, and asked if I could return in 15 minutes. Jorge and I returned to the hotel to find it open, the front desk manned by the proprietor’s teenage daughter, who also spoke very good English. I thanked Jorge for his help, checked myself into a room, and 15 minutes later was back in Miguel’s front hall/office/heavy-metal shrine.

All About Miguel

Miguel Lara was born in Juchipila. In 1959 at age 9, his family emigrated to the U.S. Miguel quickly mastered English, did well in school, and built himself a typical middle-class American life, working for Teradyne for 18 years. Sometime in the last few years, he had returned to his hometown with his two Mexican-American teenage sons, Miguel Jr. and Jose, the teenager who had greeted Jorge and me at the door. Both sons were university students in Guadalajara, and Jose, who was majoring in biology, was home on break.

Miguel Jr. and Jose are both bilingual and hold dual citizenship, but it was apparent that Jose was a bit more comfortable with Spanish. Miguel Sr. actively encourages both sons to maintain and improve their English. While at school, all email correspondence with their father is in English, which Miguel Sr. diligently checks and corrects.

Miguel supported himself in part by teaching science and English at the local high school. He asked where I was staying, and when I told him, asked if the proprietor’s daughter had checked me in, describing her age and appearance. When I indicated that yes, it was she who’d checked me in, Miguel said, “Yes. She’s in my class. I’m going to flunk her.” I objected that I’d found her English pretty impressive, but Miguel was un-moved. “She’s lazy, never studies worth a damn.”

Neither Miguel Sr. nor Jose volunteered any information concerning a mother or Miguel’s marital status, and during the first hour or so we were together I didn’t ask.

Miguel, Jose and I sat together as I explained my interest in and research on the Martinez Piñon. Miguel had never heard of Ledig nor his bottleneck theory, but he was well-informed about the tree and its history. He claimed that the tree had been known to Spanish explorers and settlers long before Rzedwoski, at least as far back as the mid-16th century. He referred to mountain on which it grows always as “Cerro Alto Piñones”, never just “Cerro Piñones”. According to Miguel, the land was divided up by 11 separate private landowners, of which he was one. Over time, Miguel and several other landowners had worked diligently to ban cattle grazing and improved seedling regeneration, but conflicts still existed with some cattle-owning landowners, as well as adjacent landowners who allowed their cattle to wander onto Cerro Piñones. Miguel and the other “tree-conscious” landowners were actively working with the Mexican government, receiving limited grant funds for their efforts at conservation and regeneration.

While discussing the topography of Cerro Piñones, I pulled out my copy of Lopez-Mata’s map. Miguel glanced at it briefly and quickly pronounced it inaccurate, pointing to a swath on the North slope of the mesa where the map indicated Martinez Piñon, and remarking that none of the trees grew that far North.

The Lara home was in the middle of a years-long expansion and restoration. Throughout the house, it was unclear where indoors ended and outdoors began, or whether one was walking through garage, home, or nursery. As we walked through the various rooms and open spaces, Miguel share with me endless details of this never-ending project: the third floor he’d added himself, the temporary bedroom for a sometime visiting American friend, who’d left his vintage pickup parked in what appeared to be another bedroom, the next-door nephew who’d destroyed one of Miguel’s load-bearing walls in the course of his one home-improvement project, and whom Miguel had sued to stop from causing further damage…

I knew when I’d planned the trip that I was coming at the wrong time of year to collect any seeds. Martinez piñon cones, like all piñon cones generally ripen sometime between August and October. I’d hoped, but didn’t expect, to come across a few seeds while scrambling around Cerro Piñones. Yet here I was with seeds all around. I’m ashamed to say that at that very moment, my first thought was whether and how to pocket a few.

Miguel rescued me from temptation: “Go ahead and take a few seeds if you like. Maybe you can try growing a few at home.” I gathered a dozen or so and popped them in a pocket.

Our tour of the Lara home continued with long explanations of past and future renovations. Finally we ascended a ladder to the roof, which commanded a beautiful third-story view of Juchipila and the surrounding valley.

You're a bold gringo. I'm enjoying this story!

ReplyDeleteThis story is stunning on so many levels. You happen to meet somebody at a tire repair shop, who not only happens to know about the pines but also happens to know one of the landowners, and he takes you to meet them, but get referred to another landowner who happens to be sympathetic to the cause of the pine and happens to have bunches of those amazing cones for you to gawk at and just so happens to have seeds for you to take home with you since you didn't arrive at the right time of year...

ReplyDeleteKarma!

"often times such a “project underway” appearance that one might consider temporary in the U.S. is sometimes a bit more permanent in Mexico"

Like every building in every town, with rebar ends butting out from atop every corner ;-)

regards--ted

SOOO cool! i wish I had stumbled upon your blog as your adventure was taking place. My family is from Juchipila and the surrounding towns and what you experienced at the tire shop is typical. Everyone knows each other, literally!

ReplyDeleteI am glad you found your tree!

SOOO cool! i wish I had stumbled upon your blog as your adventure was taking place. My family is from Juchipila and the surrounding towns and what you experienced at the tire shop is typical. Everyone knows each other, literally!

ReplyDeleteI am glad you found your tree!

Hi Maria, thanks for your comment. I loved Juchipila- the setting, the people, the landscape- everything. The kindness and assistance people showed me were just amazing.

ReplyDeleteWhile I was in town, one of the locals pointed out an American woman who'd moved down to retire in Juchipila, and I remember thinking how nice that would be. I hope to return one day.

Hi,

ReplyDeletevery interessting! I come from Germany and I collect pine cones, but this pine is really rare and I like to visit this tree on natural stand.

Every year I spend some time in the USA. But I wasnt in Mexico.

You can write an answer: zetpunkt@web.de