Note: Here’s the deal. We’re still on vacation, up in Northwestern Montana*. But I’ve already come across so much I want to blog about that if I wait till we get home later this week, I’ll be blogging about Montana till Christmas. So I’m borrowing a page out of KanyonKris’ book and starting to blog about the vacation while still on it.

Also, just a disclaimer/heads-up: I’m on a new system, with a new version of LiveWriter, and blogging from a spot with iffy access. So if there are format issues with this post or the next one, just be patient and I’ll clean things up sometime in the next week.

*New masthead photo taken yesterday morning. I need to do a post on clouds.

The Post

Driving North on I-15 out of Utah, you pass a series of low ranges in Southern Idaho before clearing Pocatello and dropping out onto the Snake River Plain.

The plain is generally flat or gently rolling, and it lasts for a couple of hours. Sometimes it’s agricultural land, but more often just open range, or scrub and lava fields. The plain breaks for good right around Spencer, just short of the Montana border, and when it does, forests start appearing again on the mountain hillsides. Although various tree guides to the West define these forests as the same type- Rocky Mountain Montane Forest- they’re different from the ones you left behind a few hours back in the Wasatch.

Tangent: I’ve previously described this family road-trip custom of riding super-early. It’s a little trickier when you’re just passing through, spending a single night. You either need to arrive in town early enough so that you can stop by a bike shop, or have really good beta- from the web or otherwise- before you arrive. Because you’ll be searching for a strange trailhead right around dawn. And you want a ride that’s fun, that’ll expose you to the local environment- whether forest, desert, or whatever- and that will give you a good workout/climb, but not be so technical that you’ll come back to your family all crabby and out-of-sorts from excessive dabbing/walking on a strange trail first thing in the morning when you’re not really awake, or worse yet, bruised from a crash. (Yes, I’ve done both.)

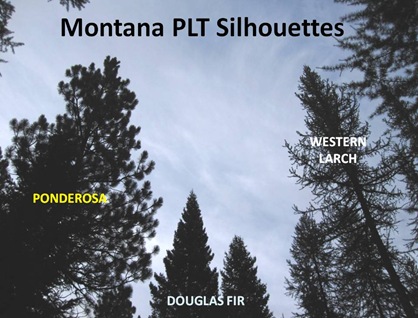

The first big obvious difference of the forest around Missoula from the Wasatch is of course all the pines- specifically Ponderosa. Though riding through open pines isn’t terribly unusual in most of the West, it’s unheard of in the Wasatch. Ponderosas are the most common tree around Missoula, and in fact for the first hour of my ride, it was one of only 2 trees I saw, the other being Douglas Fir.

Side Note: Another difference is Aspen. Though we saw plenty of Aspen later in the trip, up in and around the Flathead Valley and Glacier NP, they don’t usually seem to form the vast expanses so typical of Wasatch forests. Interestingly, when I did research for my Aspen posts last summer, one of the most intriguing things I read was that the Aspens of Montana reproduce primarily sexually, unlike ours in the Wasatch, which almost always reproduce clonally. And this difference begs the question of whether the Aspen of Montana are actually evolving faster than those in the Wasatch. Over the last 10,000 years, Aspen in the Wasatch- and most of Utah and Colorado- have effectively experienced one single, clonally-extended generation, while those in Montana have probably experienced something like 200-250 generations.

Montana’s Meanest Weed Is Way Pretty

C. maculosa is an exotic, native to Eastern Europe. It’s a member of Asteraceae, and so related to things like Dandelions and Mules Ears and Balsamroots, but belongs to a different tribe, Cynarea. In fact, the thing you’ve no doubt seen here in North America that’s much more closely-related to it is Carduus nutans, the dreaded, evil Musk Thistle.

Interestingly, factors 3 and 4 may be connected, as both appear to be the result of the Knapweed’s production of phytotoxic chemical, specifically a catechin.

Side Note: Catechins are a class of secondary plant metabolites. Primary plant metabolites are organic compounds associated with plant growth, development or reproduction. Secondary plant metabolites aren’t directly involved in any of that stuff, but rather perform other functions, like- for example- poisons.

Back in Europe, Spotted Knapweed occurs in and among other ground cover and isn’t dominant. But here in North America, our plants don’t know how to deal with, and it ends up being the only wildflower around in large areas (pic above, left). Lots and lots of countermeasures- both chemical and biological- have been, and are currently, used to attempt to control it. I read that in Glacier NP, in the high meadows near Rising Sun, rangers remove it by hand when found*.

*Whether or not that’s actually the case, I saw plenty of the weed in the park below 5,000 feet, especially on the East/Atlantic side.

All About Larch

OK, back to trees. After an hour of climbing I paused at a trail junction to pee*. As I did so I looked up and around, and noticed a couple of trees that looked different. And sure enough they were. They were Western Larches, Larix occidentalis.

*Yes, that’s right- yet another botanical discovery/observation while peeing!

*Which is, regrettably, the only time I’ve seen Larches changing color. Those would have been European Larch, L. decidua, which has supposedly also been introduced and subsequently escaped/naturalized in the Northeastern US.

But when I checked out the research* on North American Larches, I was surprised to find out that the opposite seems to be the case. Western Larch shows a much more diverse gene pool than Tamarack, which appears to have gone through some recent genetic bottleneck (presumably due to recent, repeated glaciations of its range.) If anything, Tamarack is likely to be the (wildly successful) offshoot of Western Larch!

*If you follow the link and actually read the paper, the story of Eurasian Larches is way fascinating. If you’re a plant-geek, anyway.

Side Note: I discussed genetic bottlenecks this Spring when talking about the Blue Piñon down in Mexico.

In the West, Larches don’t occur any further South than central Idaho. In a sense, they’re almost a “Boreal extension” into the Rockies, a hint of the cold, endless forest beyond.

Side Note: The other species is Subalpine Larch, L. lyalli, which occurs in Glacier NP, but which I didn’t see/ID this trip.

The Singletrack Not Taken

*Aren’t those the weirdest? You’re in a strange place, riding along, you find an obvious, well-traveled side trail and decide to follow it. Over the next mile or so it gets fainter and fainter, and eventually disappears altogether. What happened? Where did it go? Why are all these other bikers following it? Are they all just clueless out-of-towners like me?

I made it back in time to catch the hotel continental breakfast with Awesome Wife and the Trifecta. As we munched on scrambled eggs, cocoa puffs and do-it-yourself waffles*, I mused about how though we’d “lost” a few tree species on our trip North, we’d gained at least 1 new one. I didn’t yet appreciate how weird things would get as we continued North.

*Don’t those hotel/motel continental breakfasts have the oddest food combinations? I always think about European tourists coming down from their rooms in the morning, checking out these weird breakfast buffets, and thinking, “OK that’s it. These Americans are totally whacked. It is utterly beyond me how a people that eats so poorly managed to put a man on the moon.”

Next Up: The Fantabulous Columbian Forest

The mighty Larch. A very cool tree, and so big - I liked the photo with Bird Whisperer for scale.

ReplyDeleteYes, the allure of trails. It's also something I love about mountain biking - exploring new trails.

As for those cool singletracks that seem to disappear, I've learned around here that it's usually a trick by locals to keep traffic off a trail. They make it appear that the trail ends - but if you explore in increasingly larger circles, you find that it restarts. Or, you look for the obvious slash cover-up and go in that general direction.

ReplyDeleteThat mysterious new singletrack that appears at my 'turn-around time' frequently gets me in trouble with my husband on trips. I end up late, late, late.

The question about aspen evolution is fascinating. Another question is *why* some aspen rely more on sexual reproduction and others on clonal reproduction. Hmmm.

You're taking the vacation that we almost took, before deciding to go to SW colorado. Thanks for giving me a glimpse of it!

KB- you guys would love Western Montana. I'll have more pics in the next couple of posts.

ReplyDeleteI am always screwing up the return time on my family-vacation early AM solo rides. Several times I've looked at my watch and thought, whoops, I'm late, better try this "shortcut" back... which never ever turns out to be shorter...