I have 2 more posts I want to do about Maine- this one on aquatic freshwater plants* and then one on memory. It’s been tough to crank them out this week as I’m down in Brazil on business. If I get time this week I may do a completely off-topic random- observations-about-this-place-type-post, but in the meantime I’ll just share this one snippet of Sao Paulo street life. If any Portuguese-speaking reader can tell me what this guy’s saying**, they get a WatcherSTICKER.

*Yes I know, not the most exciting topic for the non-plant-lover. But as I’ve mentioned before, I have a list of things I feel I need to cover in this project, and watery weeds are on it.

**Is it just me, or does he seem tense? I feel as though he could use a stiff drink, a massage, or perhaps some aromatherapy. Maybe all 3.

The Post

This post is about ponds and plants, but first let’s talk about something else: snorkeling.

I love snorkeling. When I go on tropical vacations, it’s one of my favorite things to do. You put on a mask, look down and see this whole other world below you. With a good breath of air and a few strong kicks, you’re down 10 or 15 feet below the surface, peeking at fish, echinoderms and all sorts of cool creatures hidden among the rocks and coral. I also enjoy scuba, and certainly the world opened up by scuba is even more fantastic than that sampled by the casual snorkeler. But snorkeling has a relaxed, low-risk casualness about it that somehow captures the essence of vacation: Start and stop when you want, do it with friends or alone, minimal gear, hassle and safety checks, and if you’ve had a beer or two already, well, no big deal.

*The “drop-off” is sort of the generic term we use for “when the water gets over your head.” In many parts of the 5 Kezar Ponds there is a distinct true drop-off: the lake depth goes from about 2 feet to >10 feet in a horizontal span of only ~6 feet. But in front of our cabin there no true drop-off, just a gradual, steady deepening till you can’t touch.

So our first day at the cabin, I donned snorkel and fins and waded in. I kicked out to about 15 feet of depth and dove down to the bottom. I did so about a dozen more times, moving a few hundred feet along the shore then swam back, walked out of the water, and left the snorkel & fins indoors for the rest of the vacation. There was pretty much nothing to see. Hold that thought.

When I was younger I found weeds and pads and such growing in the water sort of icky, and always favored sandier areas, or shorelines of exposed granite, where pond-plants didn’t grow. What I didn’t realize then is that these areas are the “deserts” of ponds, relatively poor in life (including fish). Aquatic plants are a sign of a healthy lake or pond, and their presence helps to keep the pond cleaner.

Tangent: When I was a teenager, acid rain was a big worry in the Northeast. One of the side effects of acid rain is to make it difficult for freshwater aquatic plants to live, leaving “bare” lakes and shorelines. At the time, being pretty much enviro-clueless, I actually thought, “Hey that doesn’t sound so bad…” I’m even more embarrassed to admit that around that same time I first heard the idea of global warming, and thought, “Oh that sounds nice, these New England winters kind of suck…”

How Ponds Are Like Mountains

On land, the types of plants that grow are largely determined by altitude. Here in the Wasatch as you move up from ~5,000 to 11,000 feet, you pass through Sagebrush and Rabbitbrush, to Scrub Oak and Maple, to Aspen and Douglas Fir, to Subalpine Fir and Engelman Spruce, clear up to alpine tundra. What’s cool about plants in ponds is that they work sort of the same way, but in reverse, and on a way smaller scale.

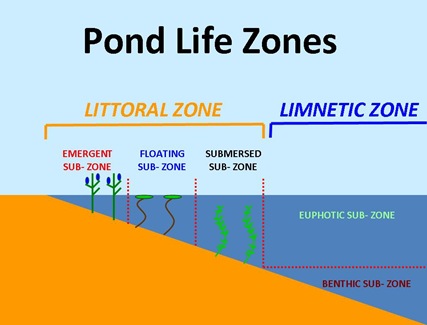

Water depth impacts aquatic plants in a few ways, probably the most important of which is that it blocks sunlight from reaching the bottom. When the amount of sunlight reaching the bottom of the pond gets down to around 1% of that at the surface, plants can no longer photosynthesize effectively. The depth at which this occurs varies depends on the lake in question and the clarity of its water, but in most lakes and ponds in Western Maine it’s probably somewhere around 12 or 15 feet.

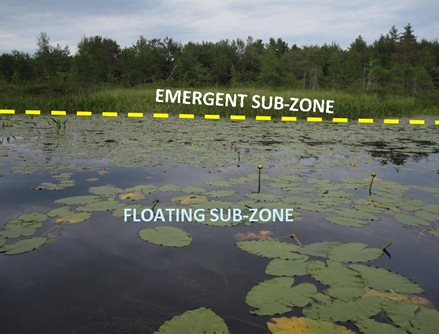

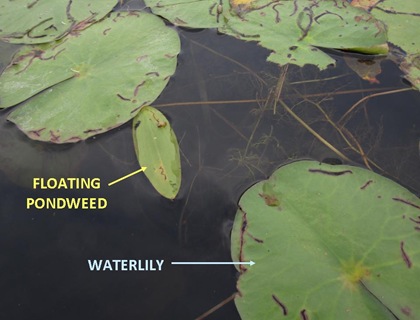

The zone between the water’s edge and this 1%-of sunlight-at-the-bottom cutoff is called the Littoral Zone, and that’s why you see things like lily pads around the edges of ponds, but not out in the middle, unless the pond is really shallow. Within the Littoral Zone are 3 distinct plant “sub-zones”, which are pretty easy to pick out from a canoe.

Tangent: I’ve been mentioning canoes a lot, because that’s how I usually poke around on the ponds. Canoes are quiet and aquadynamic*, cutting through the water gently and easily, which is nice not only because it makes paddling easier, but it creates minimal water disturbance, which is good for looking down at stuff underwater, like weeds and fish and turtles.

*Is that a word? Because if it isn’t, it totally should be.

Nested Tangent: One of my pet peeves BTW is people who can’t paddle a canoe. You know, they do 2 or 3 strokes on the left, then 2 or 3 on the right, over and over again to keep the thing going in a straight line. What’s up with that? Paddling a canoe correctly- via the J-stroke- requires about as much coordination as buttering a piece of toast. You twist the paddle away from the hull of the canoe at the end of each stroke. (Oddly, paddling a canoe is the only thing I do left-handed.)

Kayaks are even better for poking around, as they’re even more aquadynamic plus you sit lower to the water. But my favorite way to get around on the ponds is by sailing. My parents keep an old (30+ years) Sears Roebuck sunfish-type clone up at the cabin that only I ever break out. Winds on small ponds are gusty and fickle, and sailing them requires a sort weird sort of patience. You have to be willing to inch along,

*Where the Loons nest.

The most amazing, counterintuitive thing about sailing is that you can sail into the wind. Doesn’t that seem like it shouldn’t work? Like you’re cheating somehow? I think the lateen sail is one of my all-time favorite human inventions. Not just because it changed the course of history*, but because it was an innovation of such significance that required no advancements in materials science or other enabling technologies; they just starting cutting sails differently, Makes you wonder what other “lateen”-type ideas are sitting right in front of us, waiting to be discovered…

*It arguably did, enabling the European age of worldwide exploration, expansion and dominance.

The Plants, Already

The blue flowers are usually busy with Bumblebees, who collect both the pollen and the nectar, and are visited by other bees as

*Doufourea novangliae.

Extra Detail: Sunfish seem to love Pickerelweed on 5 Kezar Ponds.

*Though not as much as I dreaded getting bit by a leech. I never did get bit, though I saw friends and siblings get nailed. Interestingly, Brother Phil noted this year that none of us have spotted a leech for several years. Wonder why that is?

*Polarized sunglasses help. But if you buy your cheapie-eyewear at Maverik, using the shadow of a canoe paddle to cut the sun’s glare off the water works fairly well.

There are a number of cool submersed plants growing down in this zone. One of the more interesting is Common Hornwort, Ceratophyllum demersum. Hornworts are entirely submerged, free-floating plants, from 3 to 9 feet in “height”, rooted in mud on the pond-bottom. “Rooted” is a bit of a misnomer; the plants have no real roots, but modified leaves that anchor them to the bottom. They do well in still waters in mud/soil rich in nutrients, and provide shelter to fish-spawn and snails.

Side Note: Plant People will get why this next part is Way Cool. If you’re not a Plant Person*, you may need to go back and read this post and the “Botanical Spotlight” in this post to get it.

*Oh don’t be like that. You know what I’m talking about. You’re rolling your eyes and thinking “boooring.” Let me tell you what: We Plant People see a whole world the rest of you Plant-Blind folk don’t see. Plus we make fun of the rest of you when you’re not around.

*Because of the pollination-weirdness described in this post.

The Hornworts and other submersed plants seem to give out at somewhere around 10 or 12 feet of depth around the ponds, marking the end of the Sumbersed sub-zone and the entire Littoral Zone. Beyond this is the Limnetic Zone, marked by a lack of higher plants on the lake bottom. But the Limnetic Zone in turn is in turn divided into 2 horizontal zones. The upper waters, extending down to the ~10- 15 foot depth of the end of the Littoral- are mark the Euphotic Sub-Zone, where photosynthesis is still carried out by free-floating algae and cyanobacteria. Below this level is the Benthic Sub-Zone, where no plants grow.

Very nice post, Watcher! Pond life is something I always find oddly fascinating but never really explored when I lived back east, and now have few opportunities. Thanks for the very thorough explanation...

ReplyDeleteStreamlined is to water as aerodynamic is to air. Though I will admit that the non-word aquadynamic is much cooler than streamlined will ever be.

ReplyDeleteActually, one of my word geek fantasies is to coin a word that makes it into the Oxford English Dictionary. And when you consider that words like "bromance," "turducken," "chillax," and "frenemy" have made it into the OED, it doesn't seem the bar is very high. Problem is, two really good candidates, "Utard*," and "aquadynamic," were coined by you, not me. I'm yet to come up with anything.

*I know you claim it, but I'll wager it's an example of convergent evolution.

Aquadynamic? Tsk, tsk! Mixing Latin and Greek roots, for shame!

ReplyDelete'Hydrodynamic' is in fact a perfectly cromulent word, though strangely it isn't directly analogous to 'aerodynamic' - apparently it just means 'relating to hydrodynamics' instead of 'streamlined'. English, she is a weird mistress.

And for the record, even primitive square-rigged boats could make progress to windward, if very inefficiently (clippers could get within about 60 degrees of the apparent wind). The lateen does have some advantages, but it scales poorly and most damningly, is asymmetrical from tack to tack. Bermuda rig for the win!

// sailing geek reporting for duty.

one time in the Boundary Waters we were pushing our canoes over a beaver structure, and we stepped in what must have been an annual leach convention. feet were covered with them. it was horrifying.

ReplyDeleteThe aqua world is fascinating. Thanks for telling me more about it.

ReplyDelete