In comments to last week’s Desert Helmet-Cam Filler post, a couple of readers touched upon an aspect of the video clips that’s come up from time to time in this blog: exposure and fear of heights, or what I will refer to in this post as height intolerance.

Like most people, I’m certainly aware of exposed heights, and become uneasy if I feel I might fall. I’ve never skydived or bungee-jumped and haven’t considered myself to be any kind of “height-seeker.” But over recent years it’s become slowly apparent to me that some people- many people- are much, much more uneasy around exposed heights than I am. 3 examples stick in my mind*.

*Which I will now of course recount in painstaking detail, because- as longtime readers know- it always takes me forever to get to the point. Sometimes I wonder if this whole project isn’t just a big subconscious cover to go on and on about random stories and stuff. Which of course is the secret dream of all middle-aged men: we don’t really want power or wealth or anything. We just want an excuse to go on and on about stuff.

First Example

Side Note: When you stand on Grand View Point, Junction Butte is the big, same-height mesa partially blocking the otherwise perfect view to the South. The view from its top is the best I’ve ever seen.

The climb down off Grand View was a little hairy, with several spots where OCRick and I spotted each other and handed down packs with a short rope, and there was one section where a screw-up would’ve meant a 40 foot fall. We were cautious but not overly spooked, made it down in short order, and re-traced our route uneventfully on the return climb.

I was thrilled with our hike and couldn’t wait to return. A few months later a friend was visiting, a friend who is strong, athletic and has oodles of desert hiking/scrambling experience. After hearing my repeated raves about the hike, we rose before dawn one morning, and drove drown from Salt Lake to Grand View Point.

As we began the hike, we soon reached a minor exposed ramp where I chose to butt-sit/slide to minimize any balance issues. My friend stopped me. ‘Whoa,” he asked uneasily, “does it get any worse than this?” His tone was serious. He wasn’t kidding around.

I was confused. Of course it got way worse than this, because this wasn’t anything; the actual scary part was a ways ahead. He was nervous here? Why? What possible danger was there? We were just butt-shuffling down a short 30 degree ramp. I wasn’t sure what to say to assuage him, so I did what all cowardly friends do: I lied. “Oh no, not really… maybe just a bit, but it’s no big deal. I’ll coach you through it…”

10 minutes later we reached the crux move, the part with the 40-foot exposure. My friend froze.

FRIEND: “No way- I can’t do it.”

ME: “I know it looks scary, but it’s really no problem and I can go first and-“

FRIEND: “No. Absolutely not. I can’t do it. No way.”

I was stumped. This friend is one of the most agreeable, easy-going and yet adventurous and up-for-anything guys I know. The down-climb, while exposed, isn’t technical. I’m not a climber, but I’m pretty sure it was only class 4, maybe 5.1 or 5.2. Finally, bewildered and mildly exasperated, I down-climbed it solo, all the way to the base, then climbed back up, thinking to show him how not-a-big-deal it was. But he didn’t budge. He wouldn’t reason or negotiate with me. He was steadfast and determined; we weren’t going.

We climbed back up, drove to another trailhead and spent the day on another nice hike*. An hour or so later my friend apologized. I brushed it off; after all I was embarrassed to have tried to get him to do something he was obviously so uncomfortable with. As we talked, he asked, “Have you ever felt that way before? Just so absolutely terrified you couldn’t move? You just couldn’t do it?”

*Upheaval Dome, which has a fascinating and unsettled(?) geologic history.

Again, I was a bit stumped. I’m not particularly brave, but I’ve never been frightened- particularly by heights- to the point of paralysis. I didn’t want to say that of course, so I mealy-mouthed something like, “Oh sure, everybody gets spooked my different things…” or some such. The day turned out to be fun anyway, but the episode stuck with me. How could he have been so terrified by something that just really didn’t bother me (or OCRick) that much?

Second Example

A few years later, Fast Jimmy, I and another friend- let’s call him “Nurse Mike”- were doing an all day mtn bike ride in the same general area. The ride- which Fast Jimmy and I repeated last year- is right around 100 miles of mostly 4WD road. Close to the end of the loop, the road passes close by a rather high and exposed, but very wide and very flat, natural arch.

Now, for those of you who recognize where this is, and what the rider is doing in the video, you may possibly, depending on your viewpoint, be inclined to criticize. And that criticism may be based upon 1 of 2 different themes. The first is legality, and if this is the basis of your criticism, while I do not agree with you, I understand your criticism and acknowledge its validity. So go ahead and criticize if you like, and we’ll agree to disagree.

But the second possible theme of criticism is risk. You may feel- as at least one YouTube commenter has shared- that riding the arch is “stupid and dangerous”. And if that is your line of criticism, I must tell you that you are completely, flat-out wrong. The arch is at least 8 feet wide, with 5-6 of those feet providing a completely obstacle-free path. I’m pretty sure one could drive a small automobile- say a VW Bug or a Ford Focus- across the arch without incident. The margin for error is probably 3 or 4 times that of riding a bicycle along a suburban street in moderate traffic, where a single 2-foot swerve could kill you. It’s just not that dangerous.

Fast Jimmy and I walked and rode the arch several times, delighting in the scenery,

Third Example

Fast-forward to this past Spring. SkiBikeJunkie, Hunky Neighbor, KanyonKris and I were riding Gooseberry Mesa. At the point of the mesa, I rode out, did a little loop and returned. No one else did so, and SkiBikeJunkie wouldn’t even watch. The point-loop isn’t difficult or particularly hazardous. Watch the video.

With the single exception of the final wheel-lift over the last crack, I don’t think I’m ever closer than 2 ½ feet from the edge. Again, many of us routinely ride closer than this to moving cars, or to trees when we’re descending forested singletrack at 20-25 MPH.

Last weekend I rode the point-loop again. Out of our group of 10, no one else did. Why not? There was no other move which only I did, and several other (non-exposed) technical moves which others- in one case most of the others- did and yet I sat out. The wheeling, panoramic view is fantastic, the little wheel-lifts fun yet super-easy, the 360-end-of-world-falling-away-all-around-you sense is just incomparable, and honestly, it’s not scary (to me) at all. Rather it’s fun. It’s beautiful, it’s exhilarating. Why don’t other people feel the same way I do? How can different people feel so wildly differently about height exposure?

I was particularly perplexed by SkiBikeJunkie. He’s a far better skier than I am, and doesn’t strike me as particularly risk-averse or cowardly in any other aspect of his life. (In bike races together he’s made semi-risky moves I’ve tried to follow but flinched on.) Even when we drive to go skiing, he drives faster and more confidently on slippery roads than I do. I’m not braver than the guy. Why is he such a ninny* about heights?

*His word-choice, not mine.

Tangent: In fact, I am kind of a pussy about lots of things. I drive like an old lady in the snow, avoid technical mtn bike moves/jumps where I think I stand a good chance of falling, and am paranoid of backcountry skiing in open, avalanche-prone terrain. I mention this because this post may seem to be an excuse to go on about how brave I am about heights. It’s really not- I’m not brave about exposed heights- they just don’t seem to bother me as much as they do many other people, and that’s been somewhat of a head-scratcher for me for some time…

Nested Tangent: Fast Jimmy and I were recently chatting about a string of comments and disagreement over on another blog and FJ (who does not blog) said off-handedly, “.. and anyway all these bloggers have huge egos…” He quickly caught himself: “Not you of course, I mean other bloggers…” I wasn’t insulted; the point likely has merit, and got me thinking. Bloggers- myself included- probably do have bigger-than-average egos, and despite what we may claim, it’s almost inevitable that we use our blogs to promote our perspectives, peeves, current musical obsessions*, general worldview, and quite likely, the image we want to convey of ourselves.

*Avett Brothers. Clean Colin got me into them last weekend on the drive down South, and for the last few days I’ve been walking around humming “Talk on Indolence” and thinking about banjo lessons.

Fear Of Heights

And to answer that question, I guess we have to ask, why are people afraid of heights?

I know, I know, that’s the dumbest question I’ve ever asked in this blog, right? We’re afraid of heights because we don’t want to fall to our deaths- duh. But in the 3 examples I just gave, the height-fear wasn’t rational, and all 3 friends routinely do things- drive, road-bike, mtn bike through trees, cross city streets- entailing equal or greater levels of risk without flinching. Whatever is going on in SkiBikeJunkie’s head on Gooseberry Point, it is not conscious, rational analysis.

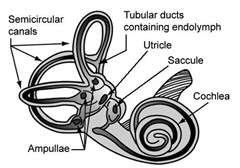

All About Balance

One of the most impressive things that nearly all of us- barring injury, infirmity or disability- do pretty much all the time is stand upright and walk around*. It’s not easy to figure out how, and human engineers haven’t come close to creating any kind of robot that can mimic human bipedal stability and gait. Our balance and posture challenges are more significant that those faced by the majority of terrestrial (quadrupedal) animals, and we handle them with a sophisticated and well-developed sense of balance, consisting of 3 primary components.

*I touched on this topic briefly in the running post I did last winter.

The first and most obvious is vision. Seeing what’s around us helps us to avoid falling down. We’ll come back to this in a moment.

*BTW, before I forget. One of the things I don’t know, and mean to research one of these days, is how birds maintain balance. Birds have totally different ears than we do, and I don’t know what- if any- role the ears of birds play in their obviously stupendous sense of balance.

Side Note: All of these words are way loaded. The most frustrating part of researching this post was how different sources use these different terms. In many cases, “proprioceptive” is used in the same way I’m using “somatosensory”, and in other sources all somatosensory/ haptic/ proprioceptive components are all lumped together under vestibular. Then there’s the “kinesthetic” sense, which sometimes is meant as the same thing as “proprioceptive”, but sometimes not…

Haptic sense is the sense of external pressures. The pressure of the ground on your feet, the chair on your butt or your hand on a handrail all provide inputs that assist in you balance. To convince yourself of the role of the haptic sense in balance, try touching a handrail when you’re on an exposed balcony or stairwell looking down. Not grabbing the handrail, but just touching it, with even 1 finger. You’ll instantly feel a bit more stable. Touching a single finger to a stable surface can reduce postural sway- which we’ll get to in a moment- by up to 50%.

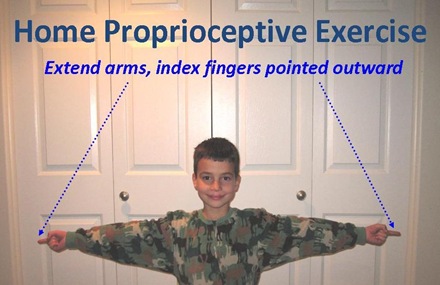

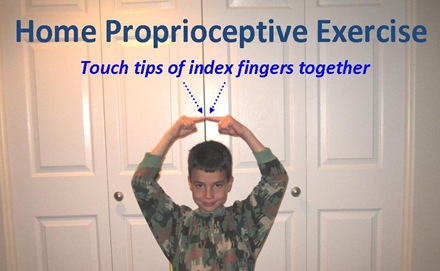

Your proprioceptive sense is your sense of where the various parts of your body are in relation to one another. It’s the reason you can close your eyes and tough your finger to your nose. You can’t see your nose, but you know where it is, right? Your proprioceptive sense allows to you eat a sandwich, rub your beard or pick your nose* while reading this post, and it’s how come you can drive a car without constantly looking to see where your hands and feet are in relation to the steering wheel, stick shift and pedals.

*Stop it. Get a tissue and then come back.

Infants don’t have much of a proprioceptive sense before about 7 – 9 months, and it’s one of the reasons they generally can’t walk before this age*.

*Interestingly, infants don’t really display much fear of heights before this age, either.

Side Note: Touching your nose with your eyes closed is actually a pretty easy proprioceptive exercise. In researching* this post I goofed around and tried several others. Here’s a trickier one: Extend both arms, with your index finger on each hand pointed outward.

**Or your reflection in your office window, you big cheater.

All three of these systems work together in a zillion really cool ways we take for granted. Here’s one you can check out right now: Pick up a paper with some writing on it. Now nod your head up and down vigorously, rapidly and repeatedly while reading it.

*The second task would probably be a bit easier if we had a higher flicker rate, which I explained in this post. Man, it is like I have a post for everything. Drink up!

This is what’s going on as you stand, walk, run or ride a bike. Your visual, vestibular and somatosensory systems are working together seamlessly and elegantly to keep balanced, upright and looking ahead. And it all works great, until we come to a cliff.

Let’s return to the visual sense. As you walk, run or bike- or even stand still- your head moves. While walking along a steady surface, or even while standing around, your body almost constantly moves in what’s called postural sway. While walking straight along a sidewalk your postural sway is minimal, maybe 2 cm side-to-side. Of course you don’t feel like you’re swaying because your vestibular and somatosensory senses are working together in your brain to align with the gently-swaying world-view coming from your eyes. In fact, your brain expects to see than swaying motion, not just from stuff you’re looking at straight ahead, but from stuff all around your peripheral field of vision, including the sidewalk/ground stretching out in front of you.

To detect motion, an image needs to move a distance of about 1/3 of one degree (20 minutes) across your retina. At modest distances, several feet ahead of you, this is no problem. 2 cm of postural sway easily equates to >1/3 of a degree and the whole system works fine.

As distance increases, subconscious head-sway increases. At distances of 50-65 feet (15-20m), 10 cm of head-sway is required to produce 20 minutes of retinal visual arc. 10 cm of head/postural sway is generally in excess of the body’s ability to stand still upright. So when you walk up to the edge of a 50 foot cliff, and the ground “in front of” you is now 50 feet away, your brain’s natural tendency is to make you sway more in excess of what your combined balance system is capable of handling, and you feel unbalanced and experience immediate fear of falling. In effect, your visual inputs are in conflict with your vestibular and somatosensory inputs, leading to the imbalance, vertigo and fear associated with heights.

But as we’ve already seen, different folks react to heights differently. What’s going on with height-tolerant individuals and how are they different from height-intolerant individuals?

Acrophobia is the fear of heights, and we incline to categorize individuals who are uneasy around heights as acrophobic, but in reality height-tolerance is a continual spectrum, with height-seeking and acrophobic individuals on the ends, and varying degrees of height tolerance or intolerance in between. Fewer than 10% of height-intolerant persons are truly acrophobic, as defined by the experience of real anxiety when just imagining exposed heights. In the old days, acrophobia was suspected- like some other phobias- to be the result of childhood/developmental trauma (i.e. getting tossed in the air or dropped as a baby) but that idea’s since pretty much fallen by the wayside. Instead it’s believed now that the brains of height-tolerant persons automatically rely less on visual input in height situations, and more on their vestibular and somatosensory senses. In essence they dynamically and subconsciously alter the “balance” or effective weighting between the 3 inputs to de-emphasize the conflicting visual inputs.

This makes sense. You don’t actually need 3 senses to stay upright. You can stand, walk or even ride a bike with your eyes closed, and there are plenty of blind skiers.

What appears to be happening in height-intolerant individuals is that their brains do not effectively de-emphasize or “de-couple” visual inputs in height situations, causing imbalance, vertigo and extreme fear at or near cliff edges. The only difference between my brain and SkiBikeJunkie’s is probably that my brain is better at “visual de-coupling” (my term) than his. I’m not braver than he is around heights, because I simply don’t experience anywhere near the same level of fear.

Tangent: But my brain’s only “better” than his with heights till I ride off a cliff. There’s a reason so many people are height intolerant- falling off cliffs is a bad thing. And, if over the next few thousand years, a dozen or so more of my descendants than SkiBikeJunkie’s ride their bikes off cliffs, then perhaps my “aberrant” tolerance will be kept in check throughout the greater population.

The good news is that for most folks, height-intolerance can be eased through habituation. Climbers, mountaineers and construction workers all routinely become more height-tolerant with experience and time. Strong corrective eyeglass-lenses or sunglasses that limit peripheral vision may exacerbate height intolerance. Touching a wall or other stationary surface seems to help, as can a walking stick or trekking pole.

But Why Are Heights Fun?

So maybe we’ve answered the initial question. But we haven’t answered the follow-on question: Why do I like riding exposed heights?

At the opposite end of the spectrum from the outright acrophobics are the height-seekers- people who actively seek out and enjoy exposed heights. This group includes skydivers, climbers, hard-core mountaineers, para-gliders and ski-jumpers. I’m nowhere near this group, but I do derive enjoyment out of riding exposed trail sections. Why?

The whole topic of risk- and specifically the evolutionary drivers behind risky behavior- is beyond the scope of this post, but we all know that some people actively seek it out. Many of us think of risk-takers as “adrenaline junkies” and tend to write them off with the same, “they’re just whacked…” attitude we assume when trying to understand UFO-enthusiasts or Sarah Palin supporters. But risk and risky-behavior is a far broader and more important topic than just base-jumping or bat-suits, and affects the lives of millions in everything from business to sex. Psychologists tend to break risk-takers into 2 groups: impulsive and contemplative. At first glance, you may equate “impulsive” with reckless, but it’s not always that simple. In business the impulsive risk-taker might well be the innovator with peaks and valleys of success and failure throughout his or her career, while the contemplative risk-taker may- or may not- enjoy a more measured career in which the successes overall outweigh the failures.

If I am a risk-taker of any kind, it’s definitely of the contemplative sort. I walked the arch and the point before I ever rode them, and my career and personal life, while rewarding, have been marked by a personal conservatism that has sometimes lead to moments of “what-if” reflection about opportunities or chances not taken. Perhaps some of my pleasure- if it can be called that- in height exposure, comes in part from understanding the true nature of the risk and mastering my own (admittedly mild) unease with it. I ride away from the point- or arch- with a feeling not just of greater confidence, but of greater awareness of myself and my place in the surrounding environment, and a hint, a whisper, of a greater, almost expanded proprioceptive sense that knows and binds my mind not only with my own limbs and form, but somehow with that of the greater world around me.

Note about sources: My most useful, concise source for this post was Love and Fear of Heights: The Pathophysiology and Psychology of Height Imbalance, John R. Salassa et al, which was based upon the work of Brandt, Bles, Arnold and Kapteyn. Other helpful sources include Visual ProPrioception: Its Role in Wariness of Heights, David C. Witherington et al, the site Dizziness Explained, Pennsylvania Neurological Associates, Sensation Seeking in Males Involved In Recreational High Risk Sports, M. Guszkowska et al, The Problems of Defining Risk: the Case of Mountaineering, Viviane Seigneur, and The Blackwell handbook of infant development, J. Gavin Bremner & Alan Fogel. Special thanks to Twins A&B for valuable research assistance, and to Fast Jimmy and KanyonKris for videography.

I never thought about head sway before. Just sitting still, as you breathe, you can notice that your body and head move slightly, and how your vision of all surrounding objects (whether moving or still) must compensate for such slight movement. OK, I've learned my one thing for today - I'm done! Thanks for all of the great info on this topic!

ReplyDeleteMy fear of heights (aka height intolerance) started young - couldn't even stand close to a window above the 4th floor. But, as you mentioned, it can be reduced. When I first started climbing/hiking 14ers, I couldn't come close to any ridge. Now, after 11 of them, it's getting easier. I didn't know trekking poles helped but good to know!

I've noticed that time helps (vision "adjust" to reduce head sway?) - if I come to a ridge, I can't look down it initially but if I slow down, gradually I can look down and feel more relaxed. Also, I noticed that my fear of heights is more accentuated going up than coming down a mountain. I don't know if it is because of the time issue (vision "adjustment"?) or the nature of the direction of travel.

My wife had the opposite reaction. She doesn't often show height intolerance, yet when we climbed Longs, I had real trouble on the exposure going up, having to stop a few times, take deep breaths and touch the walls (but she had little difficulty). Going down, the tables were turned, it was much easier for me (still no cakewalk, though) but then she started freaking out.

Man, I need to read this post in the evening, not before going to work, for the drinking game!

mtb w

I just thought a bit more about the touching issue. When feeling "height intolerant" (love that phrase!), touching a wall or the ground does make me feel better (more grounded). However, if someone touches me, it has the opposite effect. I would think that such touch would be reassuring the haptic sense but it actually excerbates the imbalance feeling. Not sure why.

ReplyDeletemtb w

Very interesting post.

ReplyDeleteI am not at all intolerant of heights and exposure and enjoy both. I also am a contemplative risk taker. I have ridden with plenty of impulsive risk taking type riders and am continually impressed with what they pull off because they seemingly have no fear (to me).

I think a lot of it comes down to what you are focusing on. When I am riding some place with exposure, I am intensely focused on the trail...to the point that I don't really see or register the exposure. This keeps all they systems working in sync:)

I am height intolerant - but only when I can fall.

ReplyDeleteIf I cannot fall, ie inside a building, behind a large railing etc, I love heights. I love the view & looking around.

If I CAN fall, I freak out. Not the outward freaking out, but the sitting down far away from the edge. Just watching your video across the arch scared me - even while I could see that it was wide & that you were fine.

I can calm myself down & enjoy the view "out" from an exposed height, but looking "down" and I have to talk myself out of the fear & vertigo.

I like adrenaline & calculated risks though - mountain biking is one of my favourite sports, and flying down technical descents is fun.

I'm really enjoying climbing at the gym right now. Very interested to see what happens next summer when I get outside - especially if I try leading any routes.

mtb w- I have to think about the person-touching thing. Seems like my kids are good with me holding their hands near cliff edges, but I wonder if it isn't me who feels better!

ReplyDeleteI climbed Longs once in, '91, and I do seem to remember one really exposed section just below the summit, on the South side.

I didn't know how all those senses worked together. I'm now amazed when I stand up and walk.

ReplyDeleteLooking forward to the bird balance post. A few weeks ago when I arrived at work I watched some Starlings balance on weeds and sunflower stalks in a gusty breeze and they were exceptionally balanced. I expected lots of wing flapping or at least tail movement to keep them upright, but they their balancing movements were almost imperceptible. I want to know how they do it.

I'm not exposure averse. I've considered the arch or point ride but decide it's not worth the small risk. If a freak gust of wind blew me over, I think my wife be ticked. And even though I've rappelled over 100 times, I still get a physical reaction - let's call it a pucker.

BTW, Amazon has a free Avett Brothers track, Shame here - http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B0041A2UBW/ref=dm_dp_trk5

Holy smokes that was awesome. What's even more awesome, is that I read the entire post and understood most of it.

ReplyDeleteNote that my ego requires that I leave a comment with the above accomplishment. Also note that my ego doesn't keep me from saying I'm a total pussy about everything. I should prolly say "p-word" instead of "pussy" (because of my gender) but I quite enjoy that word. It was a main staple during dinner time at my childhood residence. It was the one word that made everyone laugh. Insert fond-childhood-memory-sigh here.

Longs can be a beast. 3 people died on it this year, 2 on the Diamond and 1 on the Ledges section, plus a couple of other falls (including at least 1 on the Homestretch) requiring rescues.

ReplyDeleteParts of the Keyhole route, while only Class 3, does have some serious exposure. The Narrows, a 2-4' wide undulating and downsloping ledge, has about one to two thousand foot sheer drop. That's the part that got me and the one that you are probably referring to. The Homestretch, the final 300' climb to the summit, is a pretty smooth rock climb at about a 45 degree angle, also with the same 1-2,000' dropoff.

You may not find anything on the person touching me issue, it is probably more the acrophobia and less an imbalance issue.

mtb w

Rabid- Yes, but if you actually read the entire post, it means that even if you are a pussy, you're not a TORie (Tangent Only Reader). Not that there's anything wrong with either. (But personally I'd rather be a pussy than a TORie.)

ReplyDeletemtb w- It's the Homestretch, that's what I remember. Oddly I have no memory of the Narrows- I guess that's what 20 years will do... I do remember that huge, flat, super-cool summit. It was hard to start heading down.

Very cool post. Answers a question I've had for a very long time. I'm not sure the reason you give for enjoying exposure is all there is to it though. Yes, it is nice to know that if I come back from a cliff I have "mastered" it and am a better human, but it still seems to be "fun" while doing it. Is it the pleasure we get from mild exhilaration?

ReplyDeleteBTW, a few years ago evidence was found for Upheaval Dome being a meteorite impact crater. http://geology.utah.gov/surveynotes/snt41-3.pdf

Man, it is like Utah Geological Survey's "Survey Notes" magazine has an article about everything.

Somehow I fell a week behind in reading your blog (which is better than just reading the tangents, which I would never do). I read every word, it just sometimes takes a few days to set aside enough time to get it all done at once.

ReplyDeleteAnyway, thanks for explaining my irrational fear of heights. And you're right, it is irrational. I've tried the "it's wider than a sidewalk" self talk, and it makes no difference. Knowing that it all comes down to head sway makes sense. And to think, for all these years, I blamed it on my mother.