Back on US191, we sped North back toward I-70. After you pass the Moab airport, all the cliffs and domes and faults and anticlines and all the rest of the geo-drama is left behind, and the road is lined by endless, dull gray scrubby rolling plain. Even the “scrub” is sparse; mostly what you see is a lot of gray dirt. This is the layer above* the Morrison formation, the Mancos Shale.

*In many areas, there are 1 or 2 more narrow formations in between the Morrison and the Mancos: the Cedar Mountain and Dakota Sandstone formations.

Unlike so many of the Utah geologic formations we’ve looked at so far, Mancos doesn’t form any cliffs or smooth waves or arches or alcoves. It doesn’t form spires or bridges or slot canyons. It isn’t the centerpiece of any national or state park, monument. And yet, you probably see more of it driving around Central and Southern Utah than you do any other formation.

Once you get off the asphalt, Mancos is both wonderful and horrible. In dry conditions, graded dirt roads across the Mancos are often smooth and fast, allowing a passenger car to zip comfortably along at 40 or 50 MPH. But when wet, forget it. Mancos roads become a thick, gloopy stew that’ll quickly snare your 4WD vehicle.

Extra Detail: Often times when you’re tooling along some Mancos track you’ll see deep tire ruts left over from someone drove the wet road. If you check out the deep ruts, you’ll often see that they have marks from tire chains, which is how the ranchers get through when it’s wet. I used to carry around tire chains in my old pickup for just this reason, but eventually decided it was just less hassle to stay off Mancos/clay roads when potentially wet.

I always find Mancos a bit un-nerving, partly because I’ve encountered it wet, but also because it seems so bleak, and borderline lifeless. Why so few plants? ![Smectite Expansion[4] Smectite Expansion[4]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjTKU-JiX2ogGJ4sI_kjbSzPdqvkUilSzoXWC6Bbq0ChsyLmGriMOb5uYcadrgLMziNhAcb8hxB82Axk-3VMJ96f1m_Wl0nnRVBezfswLwINtcUDWP0IjjRmjOS9ZtZDshhplnCwj5dHmA/?imgmax=800)

*I covered selenium content in soils, plants and people in this post.

**I covered expanding clays in this post.

***And now that I think of it, I don’t think I’ve ever seen fully developed cryptobiotic soil on Mancos. (Though maybe I just haven’t looked hard enough.) I covered cryptobiotic desert soils in this post. Man, it is like I have a post for everything.

As you approach I-70, you’ll see a massive wall of high, beige cliffs on the North side of the freeway. These are the Book Cliffs, formed from the Mesaverde formation, layers of sandstones interspersed with shales and limestones.

I’ve driven past and along the Book Cliffs (pic left) probably a couple of hundred times. Embarrassingly, with the exception of a few quick forays over a decade ago in Colorado,

Tangent: Thinking about the Book Cliffs got me noodling about the broader issue of geographic blanks spots. By blank spots in this case, I’m not talking so much about faraway places I’ve never been to, say like Madagascar or New Caledonia, but places I’ve been right by over and over again, but never checked out. The Book Cliffs are one example. Another is- or rather was- Jack’s Peak*, until the Trifecta and I climbed it this Spring. The Canyon Range West of Scipio, the Pine Valley Range North of St. George, the Uintas West of Mt. Agassiz- all are blank spots on my mental map of Utah. Closer to home there are still dozens of draws and minor peaks in the Wasatch and Oquirrhs I’ve yet to explore, and even within 2 or 3 miles of my home there are side streets I’ve never turned down. As you think about your own home “turf”, it’s likely you can think of similar blank spots that you’ve passed by time and again for years or even decades without checking out.

*Speaking of Jack’s Peak, Since I’ve become (at least marginally) geologically-aware, I’ve learned that the peak, and the ridge leading up to it, is actually its own little anticline.

Nested Tangent: When I think about blank spots, I tend to construct an image of them in my head- how the landscape looks, the vegetation, the aspect, etc. We all do this- think about an upcoming vacation. Say you’re going to Hawaii, to a hotel you’ve never been to before. You have an image in your head of the hotel, your room, the pool, maybe the lobby. Maybe the image has been influenced in part by photos on a website or in a brochure, but it’s still in your head; when you actually get there, they layout of the place will be somewhat different.

I do this all the time in ordinary business travel. I visualize the airport, the hotel, the offices of the company I’m going to visit. Closer to home I do it when I’m going to check out a new trail; I have an image of what it will look like, which stays in my head until I get there and actually see it.

Most of the time these “blank spot visualizations” are instantly swept out of mind by the actual, real-world image once I actually get to, see, and “fill in” the blank spot. But sometimes, when I finally reach a blank spot that I’ve thought about for a long time, such as the Newfoundland range or Cerro Piñones, the visualization lingers for a bit as my mind seems to try to somehow reconcile the two. I’ve mentioned before that I have frequent dreams of “wrong geography”, where I see landscapes or actual maps that are different than real world. I wonder if the source of such dreams is the countless “blank spot maps” my mind is continually creating and discarding…

In my ideal life, I’d dedicate a day a week to checking out, and filling in, blank spots. And if I ever (unlikely) managed to fill them all in, then I guess I’d move someplace else and start over again.

First Cool Thing About The Books Cliffs

First, the Book Cliffs are the longest continuous unbroken

Second Cool Thing About The Book Cliffs

Secondly, the Book Cliffs have a rich human history, reflected in the incredible archeological wealth of the area.

Third Cool Thing About The Book Cliffs

And third (and as always, I have saved the coolest thing for last) the Book Cliffs are moving. No, no, no- I’m not talking about moving as in continental plates, yada, yada moving. Yes, of course they’re moving like that- everything is. But the Book Cliffs are moving faster; they are practically walking North across the land.

More specifically, they’re eroding across the land. In many posts we’ve looked at various example of geologic erosion. But what’s interesting in this landscape, where the geologic layers are more or less flat and non-convoluted, is that the primary direction of erosion is not vertical, but horizontal.

On I-70 we turned East, away from home, and proceeded to the Thompson Springs exit, where we left the freeway and wound our way North a few miles to the base of the cliffs.

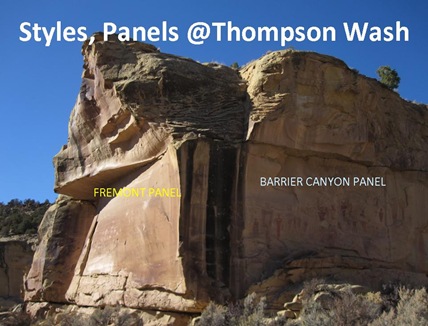

At the mouth of Thompson Wash, a modest draw in the Book Cliffs, lies an outstanding rock art site. Over the years the petroglyphs have been heavily vandalized, but restoration efforts in the 90’s removed the worst of the offending modern graffiti. Today it’s well worth a stop. Just a few miles from the freeway, the site is festooned with art spanning possibly as far back as 5,000 – 7,000 years, including at least 4 distinct periods/styles.

Sagebrush appears North of “town” and increases in height as you approach the cliffs. At the mouth of the Wash it forms small shrees, reaching over your head (pic above, right, Twin A for scale).

The first is Barrier Canyon, an archaic motif we talked about down in the Grand Canyon, and which dates back as far as 4,000 or maybe even 6,000BC. Thompson Wash is one of the classic Barrier Canyon sites, just fantastic in both details and accessibility. The main Barrier Canyon panel includes 19 large anthropomorphs, up to 7 feet tall.

*“Floaters”, specifically myodesopsia, are the results of anomalies or deposits in within the vitreous humour, which is the (otherwise) clear gel filling the interior of your eyeball. The actual floaters that you see are the shadows cast by these anomalies on your retina. I see floaters occasionally, but only when looking at bright and empty clear blue sky.

*I gave an overview of the Utes in this post.

Several thousand years, at least 4 distinct cultures/styles, mixed in with elements of neighboring styles- everything I’ve described her lies within about a 100 yard radius. And that’s the way cool thing about Thompson Wash.

That was a great Thanksgiving.

Note about sources: Geologic info came from Halka Chronic’s Roadside Geology of Utah, Lehi F. Hinzte’s Utah’s Spectacular Geology*, the Inn On The Alameda website and Utahgeology.com. Info on Thompson Wash rock art came from Dennis Slifer’s Rock Art of the Utah Region. Info on “floaters” came from Wikipedia and Awesome Wife (who’s been plagued by them for some time.)

*A fabulous book with one glaring flaw: no index. Really? A geology book with no index? Are you kidding me?

Well Watcher, you've done it again. I'm so inspired by this post that I'll have to write a whole new post to explain it!

ReplyDeleteYour adventures bring back memories, what can I say? I apologize in advance...

Nested comment!

ReplyDeleteYour observation about geographic blank spots and your subsequent reference to an anticline triggered in my mind that the laneway that runs behind my work is called Anticline Lane and I had no idea what it meant or where it came from.

I knew there was some mining connection since Ballarat, Victoria in Australia (where I live) was founded on gold mining, but I was content in my ignorance.

Thanks!!

Ray