The weather in Northern Utah is doing its usual May shenanigans; one day it’s sunny and 70F, the next it’s drizzly and 40F. The upside is that the hillsides are turning a lovely green, with all sorts of spring blooms popping up. Up higher though, it’s still Winter, and recent snows have made skiing possible weeks after (nearly all of) the resorts have closed for the season.

Wednesday Morning I joined SkiBikeJunkie, Dug, Aaron, Rick and several others for a pre-work ski up in Little Cottonwood Canyon. I was time-challenged, and so accompanied the group up to the top of the ridge dividing Big and Little Cottonwood Canyons and then skied back down solo. Once at the bottom I realized I still had some extra time, so I re-climbed about 2/3 of the track for a second, shorter run. The snow was nice, if not exceptional, and it was a bit novel to ski in mid-May, and I skied back to the car feeling happy and upbeat about the day ahead. I unloaded my gear into the car, took off my boots and slid into the driver’s seat for the ride back down the canyon. As I did so, I glanced in the rear-view mirror, and…. pffffff…. my upbeat, happy mood slipped away: I was afflicted with Chronic Helmet-Head.

As I have mentioned previously, my place of work does not have a shower. When I ski or bike pre-work I shower the night before. In the summer I take along a sun-shower and do a quick Howie-Shower to mitigate the most severe Helmet-Head. Sometimes I do so after skiing as well, but due to a recent mishap involving a rear SUV-hatch, a bike rack and a fumble, I have been without an operable sunshower this last week and a half. So all day Wednesday I worked- in the office- with a bizarrely-spiky head of hair.

Hair, the evolution of hair, and the evolution of modern human hair patterns, is absolutely fascinating. Hair- true hair- is unique to mammals*, and is one of the 5 defining characteristics** of the class.

*Insect “hairs”, BTW, are something completely different; they’re actually bristles made of chitin.

**The other 4 being mammary glands in females, sweat glands, 3 middle ear bones, and a brain with a neocortex region (which I explained in this post).

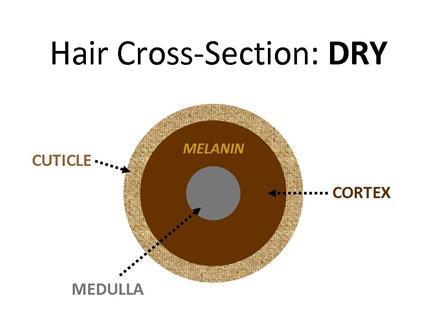

The protein that comprises our hair- keratin*- is the same protein that composes our fingernails and toenails. More interestingly, it’s nearly identical to a protein in the claws of birds and reptiles, suggesting that hair is a mammalian exaptation of an existing structure- in this case the proto-keratin protein- of our ~300 million-year-old common ancestor.

*I mentioned keratin last year, when I blogged about Porcupines, and specifically their quills.

*”Eu” of course = “good” and though I don’t know Latin, I know that “feo” = “ugly” in Spanish… That seems unfair. And wrong. I for one have always found red hair very attractive… Uh oh. I feel a tangent coming on in a footnote. In my younger years, I totally had a thing for redheads. I had 4 (that I recall) relationsh- well, “entanglements” I should say- with redheads in my early 20’s, all of which ended rather quickly and spectacularly poorly. I usually try to avoid stereotypes, but the “feisty redhead” was repeatedly true in my limited experience**.

**Although in fairness, if we were to consider all of the relationships in my 20’s that ended quickly and poorly, I’m not sure the proportion of those involving redheads would be all that much greater than the occurrence of redheads in the population as a whole.

When I say modern human hair patterns, I am talking the pattern of hairs over our bodies. I am not talking about our hair-styles (or lack thereof.) The average European* adult has about 5 million hairs on their body, of which only about 100,000 – 150,000 occur on your head. Before you protest that you don’t have that much armpit or pubic hair, the 5 million number includes both terminal and vellus hair. Terminal hair is the (relatively) thick, dark visible hair on your head and elsewhere. Vellus hair is the teeny-tiny peach fuzz all over the rest of your body. Whether you are male or female, you’re almost totally covered in hair- it’s just vellus hair.

Nested Tangent: So here’s my favorite break-room magazine story.

A given hair follicle produces either terminal or vellus hair, but what’s interesting is that a follicle can change from producing one to the other. At puberty, we typically say that young people “start growing” hair in their groin and armpits, as well as their chests and faces if male. But they were already growing hair- vellus hair- in those regions for years. At puberty the follicles switched from producing vellus to terminal hair.

A bit later, we often say that many men “lose” their hair. But they generally don’t lose it; rather the follicles on their heads stop producing terminal and switch to producing vellus hairs. We have very few truly hairless patches of skin: our palms, lips, soles of feet, behind the ears, some scars and certain areas of our genitals.

The evolution of human hair pattern, texture and color is a way fascinating topic, and way beyond the scope of this post. There are all kinds of hypotheses as to why most of our follicles produce vellus, making us effectively “hairless”, but they all have problems/inconsistencies. Almost all other land-based mammals our size are covered with terminal hairs. Marine mammals aren’t, but they have an obvious reason to be hairless- drag in the water*- and so generally compensate for the lack of warming fur with a special layer of fat. A number of really big mammals, such as elephants and rhinos, are “hairless”, but their greater mass makes heat-loss less of an issue.

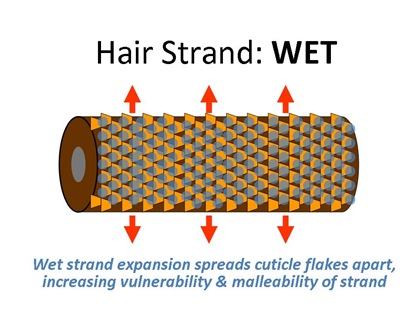

*Plus, wet hair doesn’t retain heat as well as dry hair.

Humans are thought to have become hairless around 1.5 – 2.0 million years ago, and the reason anthropologists think this is the case is because that’s when they believe the genetic mutation came about in a gene called MC1R which resulted in darker skin pigment. Prior to dark skin, it’s thought that naked*, hairless humans would fair poorly under the equatorial sun**.

*And it’s pretty certain we were naked for a long time. The best guess as to when the use of clothing became widespread is way more recent, like maybe only 70,000 years ago, a key piece of evidence being the genetically-determined date of divergence between head lice and body lice (which reside in clothing) which we looked at in this post.

**Not necessarily because of sunburn and skin cancer, but possibly because of folate-damage, as we covered in this post. Man, it is like I have a post for everything.

Why our ancestors “lost” their hair is unresolved. One long-standing hypothesis is that the loss coincided with the general drying or large areas of Africa and the formation of savanna, and may have come about to facilitate sweating and heat-dissipation. But hair also mitigates heat-accumulation, which is thought to be why we retained it on our heads…. Another, more recent, hypothesis is that hairlessness evolved as a countermeasure against parasites. Once the trend started, sexual selection could have amplified the tendency, with hairless suitors advertising their relatively parasite-free fitness. But if that were the case, why aren’t lots of other land-based animals our size hairless? And why are female humans more hairless than male humans?

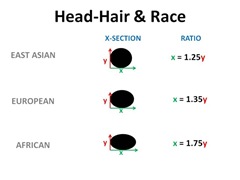

OK, lots of questions here, and I’m not going to resolve them in this post, so let’s just focus on what’s really important- my hair. Referring again to my style-afflicted photo, you’ll notice 2 things. First, I am of European descent, and second, my hair is pretty straight.

Tangent: You may also have noticed that my hairstyle is pretty lame. In fact, I have had- no kidding- essentially the same hairstyle since 1971 (minus the beard.) Certainly, as an adult man of reasonable means, I could afford to invest in some professional, modern-day hairstyling. But the truth is that at a gut level- I just feel that there is something fundamentally and distinctly un-masculine about paying more than $10 for a haircut. There, I said it.

The question is why? Was it just the case that straight hair, no longer being a liability, happened to catch on and spread through those populations? Or was there some benefit to straight hair in Northern climates? Perhaps a flat-lying head of straight hair was a bit warmer, but the most far-out hypothesis is that straight hair helps absorb UV light, which is though to be the same driver of the evolution of light skin pigment in cold/un-sunny climates. Human hair can actually transmit UV light along its length in a manner similar to a fiber optic tube!

The problem with the straight-hair/fiber-optic-UV hypothesis is that unless you have a buzz-cut- or extremely bad Watcher-style Helmet-Head- the ends of your hairs are not pointed up toward the sun. But the counter-counter-hypothesis points out that downward-pointing hair-ends are well-positioned to received UV light reflected upward from snow. See what I mean? There are like a gazillion hair hypotheses!

Back to me and my fashion-crisis. The reason my Helmet-Head is so problematic is not just because I am wearing a helmet, but because I am wearing a helmet and sweating, thereby make my compressed, mushed-up hair wet.

There’s of course an easy solution to my dilemma: a buzz cut. Many cyclists have short/buzzed/shave heads, thereby wonderfully avoiding the stylistic angst of Helmet-Head. But I’m fundamentally reluctant to do so, not out of vanity, but out of… well, let me try to explain…

Say you knew someone who was a total natural-born athlete. Some who was strong, agile, fast, with superb endurance, balance and eye-hand coordination. Now if that person just spent all day on the couch watching TV and eating Cheetoes, wouldn’t we all agree what a tremendous waste of potential that was?

That’s the deal with my hair. Because really, when you get down to it, I am a Natural Hair Athlete. I’m 46 years old, probably 80% of my friends are bald/balding/receding, but my hair is fantastically thick and healthy. Wouldn’t it be a crime- a waste of natural talent even- to buzz-cut that mane?

After I got to the office, changed, and checked email/voicemail, I walked over to the break-room for a cup of coffee. A female coworker- let’s call her “Karen”- was there and I said hi. She turned to me, and- I swear to God I am not making this up- said, “Hey your hair looks great! Did you do something different?”

And you know what? She was totally serious.

Note about sources: Info on the evolution of “hairlessness” and dark skin pigment in humans came from here. Info on the evolution and origins of hair came from here. General info on the structure of hair came from here, here, and here. Info on the fiber-optic/UV transmitting properties of hair came from here. Additional info on hair, hair evolution, and specifically vellus hair came from Wikipedia.