Everything seems better in the light of day. In most cases, I don’t know why this is.

But in the case of getting lost in the middle of the night in the desert,

Getting Found

After about a mile and a half I came to one of those merging forks that I’d completely overlooked the night before, and saw fresh tire tracks in the mud in both forks. Since I’d seen no other tracks the night before, I knew someone had come this way after me. I stuck with the South fork. Another mile and a fence loomed- the national park boundary- next to which a pickup was pulled out. An older man stood by the open tailgate, cooking breakfast on a campstove.

The man- let’s call him Gene- wasn’t entirely sure where he was either, having also wandered in in the night, but had a better idea than I did and better maps to support that idea. He was also headed for the trailhead, to day-hike down to a rock art site, and advised me on his best guess of how to arrive there. I thanked Gene and continued South. Another mile or so and the road descended into a broad, sage-filled meadow, and morphed into 2 water-filled parallel canals* of uncertain depth, extending for at least the next 100 yards. This was the worst-looking section yet, and I stopped to check it out. For about 5 minutes I waffled on what to do- go for it or backtrack? If I got stuck there was a good chance Gene would be along, but still…

*Seriously, you could have paddled a kayak down along either tire-rut.

As I equivocated in the morning sun, I heard a low distant hum, then a rumble from across the meadow. Moments later a Nissan emerged from the Piñon-Juniper on the far side.

I’ve posted before about Arizona Steve, how we met almost 3 decades ago, our parallel lives and our long history of backcountry adventures together. We generally see each other once or twice a year, and whenever we do, I’m glad to see him. But of all the times we’ve met up, I don’t think I was ever gladder to see Arizona Steve than I was Thursday morning.

*GPS with full topo map set.

**Probably part skill, part confidence, part cojones.

Side Note: The guide we used for the hike and access was the Falcon Guide authored by George Steck. His directions to the trailhead are ~20 years old, and in the intervening decades the park service has closed some of the roads described by him. Steck provides 2 access routes- one South via June Tank, the other East from Graham Ranch. The June Tank route is basically intact, is shorter and easier, but more vulnerable to rain/snow. The Graham Ranch route, which was always longer and more complicated, has changed significantly.

One gets the sense that conditions in the canyon may have also have changed. In some cases, Steck describes a bypass for a trivial obstacle, but then makes no mention of a fairly challenging section less than ½ a mile down-canyon.

*Jumble of boulders immediately up-canyon from the conglomerate arch.

**Jumble of boulders just below junction with Northeast arm of the canyon.

The Tuckup trailhead lies on the North Rim of the Grand Canyon at roughly 5,800 feet,

Botanical Side Note: Just below the rim, occurring sporadically down a few hundred feet, was this holly-like bush with tough, leathery, sharp-spiked leaves. It’s Fremont’s Mahonia, Mahonia fremontii, and it’s very closely-related to (same genus) Oregon Grape*. Like Oregon Grape it’s an evergreen. I’ve seen this shrub all over Arizona, as far South as the Ajo Mountains down by the Mexican border, but I haven’t come across it in Utah, though the guides say it occurs in the Southern part of our state as well.

*BTW, there’s an error in the Oregon Grape post: I listed it as belonging to Ranunculaceae, the Buttercup family. It- and Fremont’s Mahonia- actually belong to Berberadiceae, the Barberry family, and both families belong to the order Ranunculales. Sometime soon I will get around to fixing the error. I know nobody cares about this but me, but I’m trying to correct old mistakes when I can.

We dropped off the Kaibab Formation and descended a short sloping, crumbly section called the Toroweap formation, laid down in a warm, shallow intermittent/recurring sea bottom some ~255 - 270 million years ago. Rocks in here are supposed to be great spots to hunt for marine fossils, but both times we passed through this layer- the very, very beginning and very, very end of the trip- we were blowing through pretty quickly. Immediately below the Toroweap we passed through another cliff-y band, the Coconino Sandstone, which I blogged about back in July on the Kaibab Plateau. Below the Coconino is a long band of soft crumbly shale slopes, which might have been tricky when dry, but full of moisture from the recent rains were a breeze to pass over. This is the Hermit Formation, thought to consist mainly of freshwater stream deposits on a broad coastal plain some ~280 million years ago.

*On backpacking trips I bring 1 extra T-shirt, 1 extra pair of underpants and 1 extra pair of socks. Changing into the clean T-shirt is always a little mini-highlight of the trip. After 3 or 4 dusty, sweaty days, the detergent and fabric-softener smell of a clean tee is like this wonderfully shocking little concussion of sudden hygiene in the desert.

At the bottom of the Hermit slope, the land flattened out into a broad terrace ringing the canyon on all sides. This terrace, which occurs pretty much the length of the Grand Canyon, is known as the Esplanade, and geologically it marks the transition from the Hermit shale to what is known as the Supai Group. The Supai consists of 3 mixed limestone-shale formations*, capped by a layer of harder Sandstone, the Esplanade Sandstone. This cap-layer is harder, erodes more slowly than the Supai formations below or the Hermit above, and is the reason for the terrace. We crossed a short stretch of Esplanade and dropped into a side canyon.

*Specifically- from topmost layer moving downward- the Wescogame, Manachaka and Watahomigi, none of which are particularly spectacular, despite their thoroughly awesome names, so it’s pretty easy to miss the transition from one to the next as you’re hiking along if you’re not paying close attention.

Though it looks superficially similar to some of the slickrock you see up around Moab or Canyonlands, the

The Ancient Gallery

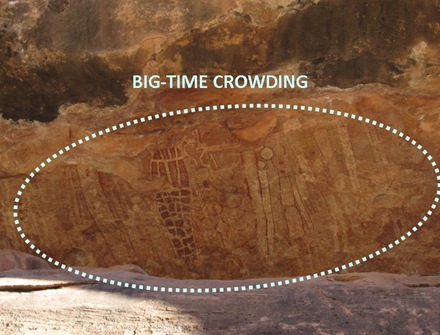

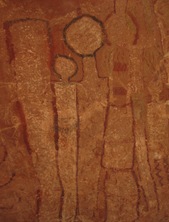

But all that was still ahead. Just a ~1/2 mile down-canyon, as the first red bluffs rose on our left, we spotted them: looming ancient figures gazing down on us from the overhang above. We’d reached Shaman’s Gallery.

*Though the Harvest Scene is pretty phenomenal as well.

Extra Detail: The site is not without controversy. A little googling of “Shaman’s Gallery” will quickly reveal something of the controversy surrounding the site’s discovery, location, publicity, access and even name. I won’t try to re-tell the various sides of the issue here, but we were disappointed to spot a bit of modern graffiti on the panel*.

*Which shocked us, given the tedious, time-consuming access to the site. You have to want to get to this place. Rock Art defacement isn’t unusual, and I’ve seen plenty of it around St. George and along the upper Paria River. But I’m still always amazed that people do it. There are some cases- the wholesale lifting/removal of panels- that can at least be explained by greed, but the more destructive defacement boggles my mind. Ultimately the root causes can only be malice, ignorance or both. I like to think more of the latter than the former, because I like to think that ignorance can (at least theoretically) be cured, but maybe I’m just kidding myself.

All About Style

Rock art in the Southwest spans a period of several thousand years, and unsurprisingly, styles varied considerably over distance and time, like culture and language. I did another rock art post late last year over around St. George, and most of the art highlighted in that post was what would broadly be categorized as Anasazi*.

*Except for the stuff over by the Maverik- that’s definitely Archaic, Fremont I think.

Extra Detail: Some of the stylistic differences between rock art styles and periods are obvious. For example, if you see a guy on a horse, you know it was drawn after European contact. If you see bow and arrow you know it’s Anasazi, specifically Basketmaker III or later, because the bow and arrow doesn’t appear to have been widespread in the Great Basin before around 500 AD.

Extra Extra Detail: Ever wonder how the Indians got the bow and arrow? I always assumed they’d invented it independently of the (much earlier) Old World invention, and thought it a charming example of “convergent innovation.” But it’s actually thought that it was introduced to the New World via the Arctic some 5,000 years ago by one or more of the “Paleo-Eskimo”* groups. Bow & arrow seemed to be largely “stuck” in the Arctic until around 0 AD, at which time it started moving Southward.

*“Paleo-Eskimo” is a huge, huge brush-over of human history in the Arctic over the last several thousand years, which I regret, but the fascinating and unresolved story of the Thule, Dorset and other ancient Arctic cultures is simply too big a tangent even for me for bite off.

I’ve seen several Barrier Canyon sites before, and initially assumed Shaman’s Gallery to be another. But it turns out to be something different- the Grand Canyon Polychrome style (GCP). GCP is similar in many ways to Barrier Canyon and is thought to be derived from it. But it shows a number of interesting differences. The humanoid/anthropomorph figures tend to be more crowded- almost lined up.

The panel contains multiple “overwritten” figures, and it’s difficult to tell what was drawn when. Some of the elements, such as the whiter pigments, appear to be much later additions, possibly from Anasazi times. In other words, this panel was probably revisited, and added to, over as much as a few thousands years. When the later artists visited the site, they likely viewed it as something already cryptically ancient, left behind by an unknown and mysterious people. The span of time separating the later artists from their predecessors was likely several times longer than the time separating us from the last artists.

In fairness, this bias is understandable; we just don’t have clear written

Arizona Steve shouldered our packs and remarked at our good fortune. We’d found each other in good time, started our trek more or less on schedule and already had seen a wonderful site. We stepped back into the bright sun and continued down-canyon, our thoughts shifting to water and campsites.

Next Up: The plant KanyonKris should never screw around with.

Note about sources: Geologic info for this post came primarily from Bob Ribokas’ Grand Canyon Explorer site, Stephen R. Whitney’s A Field Guide to the Grand Canyon and Wikipedia. Rock art/archeology info came from Mary Allen’s Grand Canyon Polychrome Pictographs site, James Q. Jacobs Rock Art Pages, and Dennis Slifer’s Guide to Rock Art of the Utah Region. Info on the (apparent) introduction of the bow and arrow to the New World came from the paper The Introduction of the Bow and Arrow and Lithic Resource Use at Rose Spring, by Robert M. Yohe II.

7 comments:

Is there some plant with a neurotoxin that only kills people named Kris?

I find it fascinating to think about peoples of the past - how they lived. But I have a hard time calling anthropolgy a science - seems you need a time machine to prove most hypothesis. Still, it's worth investigating.

Nice pic of the Watcher truck. That's the way its supposed to look. Good job getting yourself out the mud.

I am always amazed at the visible geology in the desert areas. Most of the US is covered in dirt/clay/etc so you can't see a lot of the geology without digging but in the desert West, so much is readily apparent (at least to those with trained eyes). Besides, it is just cool to look at and what colors! Oh, the colors! (Ok, that last bit is a play on the "plants" that you are going to delve into).

The degradation of rock art just sickens me. I would have no problem with posting these sites and making them publicly available but I know you can't due to the scum bags/idiots who think its funny to deface these invaluable drawings. But, I suppose the natives who drew over the older drawings may have been thinking the same thing.

Can't wait for the next installment!

mtb w

Watcher, welcome to the Arizona Strip. I have found it is a place of flat tires, flat spare tires, broken clutches, fried engines, mud, broken chainsaws, poor cell coverage (altho it is MUCH better than it used to be), etc. Seriously, I can always count on something to go wrong when we go out there. And I've been out there a lot. (I know, I'm kind of slow getting the hint.)

Quick story of my own Tuckup trip. My great-grandfather used to run cows out there (and in Little Tuweep) and my dad always wanted to go out there so one late March we left town early and arrived at the trailhead shortly after daybreak. We visited Schmutz Spring (named after aforementioned progenitor and then hiked around to Cottonwood, passing the mine shaft on the way. Unbeknownst to us we also passed the panel (we went above it).

The big story is that after we got out (about 6pm) we found out the battery in the truck was dead and no room to roll the 3/4 ton GMC to try and start it. I hiked about 16 miles to June Tank and then to the main road. About 1AM my mother and father-in-law came looking for us, picked me up and we went a got dad. Got home about 5 in the morning!

John- That sounds like a brutal trip. You are a tough man to hoof it clear past June Tank to the Mt. Trumbull road after doing that hike.

mtb w- Interestingly, altered vision will be covered in tomorrow's post...

Kris- don't worry- tomorrow's featured plant is an equal-opportunity killer.

Watcher,

I was younger then! But what was interesting that several places along the way the road would cross patches of blacker soil. A few minutes examination would quickly turn up evidence of Native American life, usually broken pottery and flint shards. And this would be out in the middle of a flat, far from any known spring. Of course, there was a time when the area was wetter and supported more people. You can walk just about anywhere out there and within minutes find similar evidence. Oh, for a time machine!

By the way, looking forward to the rest of the Tuckup posts.

John forgot to mention the "modern" graffiti is actually the writings of his (and mine) great aunt and uncle both of which were born in the 1880's.

John, Good hike, But not as bad as when I walked out clear to Wolf hole and took me three days, What was funny is when I seen the first people in three days it was some Buddie brothers running cows with a 4 wheeler, when I seen them at about a mile away I put on a cheap space blanket so they would see me,, at first when they spotted the reflextion way out in the distance they must have thought I was a space man because they approched very slow with guns out, I laughed so hard I was rolling in the dirt, any how after there chores they gave me a ride to St George,,:), Kind REgards Gordon Smith of Gordons panel.

Post a Comment