So I meant to include one more thing in my last post about acorns, but I totally spaced it. But since it’s like my best wildlife photo ever, I’m posting an update. Here it is, the Acorn Weevil, Curculio nucum. (Disclaimer: I’m not sure on the species- see below.)

Side Note: Seriously, is this a great photo or what? When I think of how far I’ve come as a wildlife photographer this year, it almost makes me weepy…

Lots and lots of acorns around here have teensy-weensy holes. The holes are almost always caused by Acorn Weevils or Gall Wasps. Both lay eggs in acorns, which their young use as a food source. I read somewhere that 25% of acorns in North America fall prey to Acorn Weevils, but I’ll bet it’s higher here in Utah; it’s hard to find an acorn without a hole in it, and this is one of the big reasons that scrub oak in the Wasatch reproduces clonally so much more frequently than by seed.

Depending on who’s counting, there are between 30,000 and 60,000 bugs in the world called “Weevil”.

Weevils are characterized by a long snout or beak which has evolved to bore into plants. The tiny mandibles are at the very end of the snout, so it chews into whatever plant matter it’s boring into. All Weevils are grouped together in the “superfamily” Curculionidae (which appears to be a monophyletic grouping, but I’ve been unable to confirm this in my brief review of the research…) which includes several thousand different genera.

I took these photos in a stand down by Dimple Dell that was practically covered with weevils; probably every 3rd acorns had 1 or 2 weevils on it, and every other acorn had at least 1 hole. Acorn Weevils belong to the genus Curculio, which includes around 350 species worldwide. I believe C. nucum is the most common around here, but that’s conjecture; I’m having trouble confirming it. In any event, after mating Curculio females search out a suitable acorn, bore a hole in it, stick their ovipositor down the hole, and lay an egg. Over the next few weeks the egg hatches and the larvae slowly eats its way out of the acorn. When it emerges it either crawls or falls to the ground and buries itself in the soil, pupating over the winter, and emerging as an adult the following spring to repeat the cycle.

I took these photos in a stand down by Dimple Dell that was practically covered with weevils; probably every 3rd acorns had 1 or 2 weevils on it, and every other acorn had at least 1 hole. Acorn Weevils belong to the genus Curculio, which includes around 350 species worldwide. I believe C. nucum is the most common around here, but that’s conjecture; I’m having trouble confirming it. In any event, after mating Curculio females search out a suitable acorn, bore a hole in it, stick their ovipositor down the hole, and lay an egg. Over the next few weeks the egg hatches and the larvae slowly eats its way out of the acorn. When it emerges it either crawls or falls to the ground and buries itself in the soil, pupating over the winter, and emerging as an adult the following spring to repeat the cycle.

3 Cool Things About Weevils

There are 3 amazingly cool things about Weevils, which I will list in order of coolness. The first is like Wasps, they’re an incredibly diverse group of insects that all share a common behavioral schtick, but have diversified into a gazillion species, each of which has zeroed in on a specific plant target/host.

The Weevil “schtick” is to parasitize plants to host its eggs. There are Weevils that go after cotton (the Boll Weevil, Anthonomus grandis, right) Weevils that go thistle buds (Canada Thistle Bud Weevil, Larinus planus) and weevils that go after leaves, fruits, leaf-buds, cactus pads, palm fronds- you name it.

The Weevil “schtick” is to parasitize plants to host its eggs. There are Weevils that go after cotton (the Boll Weevil, Anthonomus grandis, right) Weevils that go thistle buds (Canada Thistle Bud Weevil, Larinus planus) and weevils that go after leaves, fruits, leaf-buds, cactus pads, palm fronds- you name it.

Tangent: The Wasp “schtick” is similar; they lay their eggs in living things as well, but more often the target is animal (unlike Weevils, who target only plants.) There are specific Wasps that target everything from Tarantulas to caterpillars to figs.

Nested Tangent: In this “schtick” aspect, Weevils and Wasps remind me of one of my favorite bands of the 1970’s: The Undertones. The Undertones had a “schtick”: every song had one really great, really catchy guitar riff. And that song would play that riff over and over again, just beating the crap out of it (but in a good way.) Each riff was unique, but each song had a very clear, very obvious riff. The Undertones were like a biological “family”; their “schtick” was a great guitar riff, and their songs were analogous to individual “species”…

Nested Tangent: In this “schtick” aspect, Weevils and Wasps remind me of one of my favorite bands of the 1970’s: The Undertones. The Undertones had a “schtick”: every song had one really great, really catchy guitar riff. And that song would play that riff over and over again, just beating the crap out of it (but in a good way.) Each riff was unique, but each song had a very clear, very obvious riff. The Undertones were like a biological “family”; their “schtick” was a great guitar riff, and their songs were analogous to individual “species”…

Nested-Nested Tangent: But the absolutely coolest thing about The Undertones was the name of their lead singer: Feargal Sharkey. If I ever have a third son, I swear I’m naming him “Feargal”…

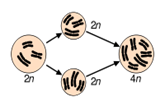

The 2nd cool thing is that some Weevils are polyploid. We’ve talked about polyploidy in whole bunch of plants, but never animals. (For an explanation of polyploidy, see this post.) For a while biologists thought polyploidy was exclusive to plants, but over the years it’s been found in a few animals, including Salmon, Salamanders and Weevils.

The 2nd cool thing is that some Weevils are polyploid. We’ve talked about polyploidy in whole bunch of plants, but never animals. (For an explanation of polyploidy, see this post.) For a while biologists thought polyploidy was exclusive to plants, but over the years it’s been found in a few animals, including Salmon, Salamanders and Weevils.

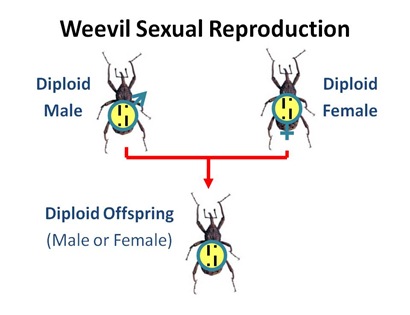

And the 3rd cool thing is that a number of Weevil species in which polyploidy occurs- in different genera on multiple continents- have adopted a Dandelion-like genetic strategy.

Way back in April, when we looked at Dandelions, we saw that in Europe sexually-reproducing chromosomally diploid Dandelions live alongside apomictic, asexually-reproducing, chromosomally triploid Dandelions.(For an explanation of the absolutely wild genetics of Dandelions, see this post.) Incredibly, something similar seems to be going on with Weevils. In multiple cases a single species includes both diploid and polyploid races (specifically either triploid or tetraploid.) The diploids reproduce sexually, but the polyploids- all females- reproduce only parthenogenetically.

Side Note: We also talked about a Dandelion-ish sexual/asexual animal reproductive strategy last month when we looked at Aphids, but polyploidy wasn’t a factor with those guys…

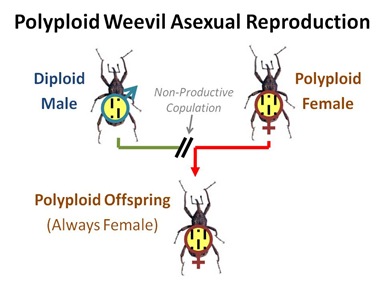

What’s even weirder is that the polyploid females compete with diploid females for, and copulate with, diploid males, but the copulation is completely non-productive; the polyploid females just produce copies of themselves.

Tangent of Great Weirdness: When I read about these bizarre mating strategies I can’t help but try to imagine them in the human world. Imagine that the world was filled with 2 types of women; both consorted with and had sexual relations with men. But some portion of the women, who otherwise appeared “normal”, only become pregnant with, and gave birth to, copies of themselves. Is that like a freaky sci-fi plot or what? Only it’s not- it’s how things really work for (some) Weevils!

Man, I should do a Bug Blog next year. Bugs are way cool.

No comments:

Post a Comment