I’m in San Diego this week, at my company’s annual user conference. It’s a busy week, with work-days running from about 7AM to 10PM, and leaves little time for actually stepping outside of the hotel, much less blogging. Still, I managed to squeak in a quick and successful tree-hunt Monday that I’ll blog about in a moment. But first, let’s talk about work.

I’m in San Diego this week, at my company’s annual user conference. It’s a busy week, with work-days running from about 7AM to 10PM, and leaves little time for actually stepping outside of the hotel, much less blogging. Still, I managed to squeak in a quick and successful tree-hunt Monday that I’ll blog about in a moment. But first, let’s talk about work.

Given the length and subject matter of my posts, it may surprise you- if you don’t know me in real life- to learn that I actually do hold a steady job, and that while engaged in that job I actually manage to stay pretty focused and not go off on tangents every 90 seconds or so. Specifically I’m the head of sales for a technology research company, and manage about 30 salespeople in the US, Canada and Europe. So our user conference is a pretty busy time. We have about 1300 attendees, pretty much all of whom are existing clients whom we want to keep happy, or prospective clients whom we hope to convert into paying clients, and so the week necessitates me being “on” pretty much all the time.

Tangent: So how did an obsessive outdoorhead-amateur-botanist wind up selling hi-tech services to Fortune 500 companies? Well, it took me 40 years to figure out what I was into. This- the whole project/plant/blog thing- is my mid-life crisis. Some guys find Jesus, some guys get into golf or gambling or singlespeeding or fast cars, some guys get a second, better, prettier wife*. This is my mid-life crisis, and so far it’s been a lot of fun.

*Well, technically I did that too. But that was back in the late 90’s, before this mid-life crisis.

Public Speaking vs. Blogging

The most stressful part of the week was Wednesday morning, because it entails me kicking off one of the conference tracks, which involves speaking to an audience of a couple hundred people, which coincidentally is roughly the same number of people who read this blog daily. Strangely, I never get nervous or uneasy blogging, and I guess that’s because of the comfortable “distance” of the web, or perhaps because of my passion for the subject matter.

Oh wait, no, that’s not it. I don’t get nervous blogging because you guys don’t actually pay me anything, and you can’t fire me. It’s kind of like being Lieutenant Governor, except without the salary.

But now that I’m over the hump and back to my routine duties of glad-handing and selling, I can take a moment or two to share Monday’s tree-hunting adventure.

The Tree

A year ago I did a 2-post series about coming out for this same conference. In those posts I described how I flew in early Monday, rented a car, zipped around and located 2 new pines: Torrey Pine and Coulter Pine. And I mentioned that, successful as the day was, I was unable to successfully locate one of my original targets, the Sierra Juarez Piñon.

As long-time readers know, I am mildly (OK very much so) obsessed with piñons. I love everything about them- their form, their spacing, their smell, their nuts and the semi-arid landscapes in which they grow. But despite my passion for them, I’ve only actually seen and touched 3 species in the wild: Singleleaf and Colorado Piñon here in Utah, and the remarkable and mysterious Martinez (Blue) Piñon of Zacatecas, Mexico.

2 other piñons grow in the desert ranges of Southern California: Sierra Juarez Piñon, Pinus juarezensis, a 5-needled pine, and Parry Piñon, Pinus quadrifolia, which interestingly, usually has 4 needles. But not always. Sometimes it has 5 or 3 or even 2 or 1 needles per fascicle, all on the same tree. And because of this variability, more than 30 years ago Ron Lanner (my Pine hero, whom I blogged about in this post) “reduced” it to hybrid status, determining that it was more likely a hybrid between P. juarezensis and P. monophylla, which also grows in Southern California.

5-needles is thought to be the ancestral state for all piñons, and all pines in general. Utah has two 5-needled pines, Limber and Bristlecone, but if you want to see a 5-needled piñon without going to Mexico, Sierra Juarez Piñon is probably you’re easiest bet.

So although I had a great day out here last year, I left just a titch disappointed not to have located my target piñon. When I landed in San Diego Monday morning, I was determined to find it.

At the gate, and couple of co-workers were waiting for me to share a cab, and I politely brushed them off with a, “I’m doing my own thing.” I headed instead to the rental car shuttle, picked up a mid-sized sedan, and jumped on I-8 heading East.

Tangent: Last year I had a great cover story, built (very loosely) around a kernel of truth involving my godparents and the book, “Everything You Always Wanted To Know About Sex But Were Afraid To Ask.”* But unfortunately, today, a year later, several co-workers regularly read my blog (though they pretty much never comment.) So I knew I’d be outed on any cover story right quick, and decided to just be vague and loner-ish instead.

*It really was an awesome cover story. Go back and check it out.

Nested Tangent: One of my few regrets in this whole project was telling 2 coworkers (who told 2 more, etc., etc.) about it. In not keeping this blog secret from them, I’ve passed up countless rich tangents involving them. Ah well, I’ll get it right next time.

Driving East out of San Diego initially wasn’t cheery. I was tired from the short night, it was hot, and the sky, although sunny, had that distinctive Southern California haze/smog. I pulled off at a soul-less La Mesa exit for a drink and a snack and thought of the sad irony of Southern California: that the spectacular scenery and climate is so limited to a tight, unaffordable coastal strip, and by necessity most folks end up living in tract houses 20-30 miles inland in hot, dry, hazy valleys.

Driving East out of San Diego initially wasn’t cheery. I was tired from the short night, it was hot, and the sky, although sunny, had that distinctive Southern California haze/smog. I pulled off at a soul-less La Mesa exit for a drink and a snack and thought of the sad irony of Southern California: that the spectacular scenery and climate is so limited to a tight, unaffordable coastal strip, and by necessity most folks end up living in tract houses 20-30 miles inland in hot, dry, hazy valleys.

But as I continued East, the land rose, the haze lightened, the development sputtered out and as the sky gradually transformed in a brilliant clear blue, my spirits lifted. At Alpine, I pulled off the freeway and into the ranger station, seeking beta on possible SJ Piñon locations.

After a bit of a wait, while the desk-rangerette explained camping “term-limits” policy* at length to a hard-of-hearing caller on the phone, I inquired about possible locations to locate the target pine. She looked at me as if I’d just asked where to score drugs. Clearly she had no idea, but at my prompting tracked down another woman in the office, who, while unfamiliar with the SJ Piñon, thought she knew the whereabouts of “some” piñons. This wasn’t ideal- P. monophylla also occurs in SoCal and I wasn’t nuts about a wild goose-chase to track down the same piñons I see back home, but it was the best I could learn, and so I jumped back in the rental car and continued East.

*It’s 14 days on USFS land. The caller evidently had a problem with the limit. Do people really stay in the campsite longer than 14 days? Really? They don’t get antsy after a week or so?

Tangent: I’m always kind of stumped by Forest Service employees who aren’t at all into trees. I’m like, “OK, you work for the FOREST SERVICE. The forest is comprised of TREES. You’re not interested in them. Tell me again why you wanted to work at the FOREST SERVICE?”

On the other hand, I guess they could reply, “OK you work for a TECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMPANY. Your company covers IT…”

Past the little community of Pine Valley I exited the freeway and headed North on the Sunrise Highway, into the Laguna Mountains. I’d traveled up this same road the year before to find Coulter Pine, but turned back after climbing into a full-on Jeffrey Pine forest (pic left). But the Forest Service lady had recommended continuing onward and upward, suggesting that piñons might occur on the steep East-facing escarpment of the range. So up and up I drove, past Coulter and Jeffrey Pine and California Black Oak, into a high, cool, open forest.

Past the little community of Pine Valley I exited the freeway and headed North on the Sunrise Highway, into the Laguna Mountains. I’d traveled up this same road the year before to find Coulter Pine, but turned back after climbing into a full-on Jeffrey Pine forest (pic left). But the Forest Service lady had recommended continuing onward and upward, suggesting that piñons might occur on the steep East-facing escarpment of the range. So up and up I drove, past Coulter and Jeffrey Pine and California Black Oak, into a high, cool, open forest.  I passed the little hamlet of Laguna Mountain, ever more skeptical of finding piñons anywhere near this high, cool, wooded range. But a mile or so further, I sensed the forest thinning and opening a bit to my right/East and on impulse I pulled off on an old, potholed, single-lane road, and without losing elevation, the forest immediately opened and ended. I rounded a bend to the left and… the world fell away (pic right)

I passed the little hamlet of Laguna Mountain, ever more skeptical of finding piñons anywhere near this high, cool, wooded range. But a mile or so further, I sensed the forest thinning and opening a bit to my right/East and on impulse I pulled off on an old, potholed, single-lane road, and without losing elevation, the forest immediately opened and ended. I rounded a bend to the left and… the world fell away (pic right)

After nearly 20 years of living in the Intermountain West, I still can’t get quite get my head around the suddenness of transition between environments. Back East, where such transitions occur, they occur gradually, over day-long drives or all-day climb/hikes. But here in the West, amidst the frequent clashes of altitude, exposure and rain-shadow, such transitions happen suddenly, almost violently, in a way that both dazzles and yet somehow offends a native Easterner’s landscape sensibility all at once. The Eastern escarpment of the Laguna range falls off precipitously, changing from forest to scrubby woodland in a space of 50 feet, and then rolls down through layers of scrub, then barren desert, down, down, down to 6,000 feet below.

Along the open ridge, amidst Birchleaf Mountain Mahogany (pic left) and live Scrub Oak, were set scattered, stout, small pines, with the distinctive silhouettes of piñons. I pulled over and started scrambling. Even 30 feet away it was obvious they weren’t Singleleafs. After you’ve looked at Pines for a while, the difference between 5 and 1-or 2-needled pines is almost immediately obvious.

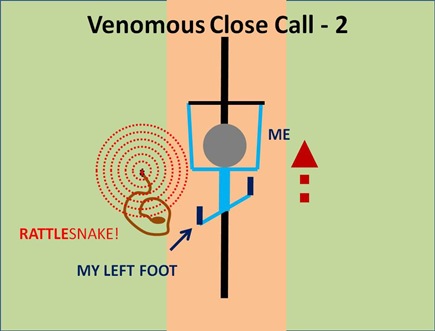

Along the open ridge, amidst Birchleaf Mountain Mahogany (pic left) and live Scrub Oak, were set scattered, stout, small pines, with the distinctive silhouettes of piñons. I pulled over and started scrambling. Even 30 feet away it was obvious they weren’t Singleleafs. After you’ve looked at Pines for a while, the difference between 5 and 1-or 2-needled pines is almost immediately obvious.  There’s a brushy “fullness” of foliage to the more densely-needled pines. Picking my way through and around the scratchy shrubs and prickly pear (with an eye out for snakes) took a few moments, but I soon reached the first of the piñons. The fascicles bore needles in groups of 2, 3, 4 and 5. On my first try, I’d found a Parry Piñon.

There’s a brushy “fullness” of foliage to the more densely-needled pines. Picking my way through and around the scratchy shrubs and prickly pear (with an eye out for snakes) took a few moments, but I soon reached the first of the piñons. The fascicles bore needles in groups of 2, 3, 4 and 5. On my first try, I’d found a Parry Piñon.

Over the next ½ hour I carefully picked my way to ~1/2 dozen more Piñons; all were pretty consistently 5-needled, marking them as Sierra Juarez.

Over the next ½ hour I carefully picked my way to ~1/2 dozen more Piñons; all were pretty consistently 5-needled, marking them as Sierra Juarez.

The season was wrong for seeds, but several bore green developing cones which should be ripe come Fall.

The season was wrong for seeds, but several bore green developing cones which should be ripe come Fall.  And eventually I was able to find and collect a few of last year’s cones on the ground below. The short, stiff needles are completely unlike those of the other 5-needled piñon I’ve visited- the Martinez Piñon- and in fact reminded me more of the short, dense, “bottle-brush” foliage of Bristlecone Pines. The fullness of foliage gives them a lush attractiveness for a piñon. We recently planted a Colorado Piñon (the only species available through local nurseries) in our yard and I found myself wishing I could’ve planted a

And eventually I was able to find and collect a few of last year’s cones on the ground below. The short, stiff needles are completely unlike those of the other 5-needled piñon I’ve visited- the Martinez Piñon- and in fact reminded me more of the short, dense, “bottle-brush” foliage of Bristlecone Pines. The fullness of foliage gives them a lush attractiveness for a piñon. We recently planted a Colorado Piñon (the only species available through local nurseries) in our yard and I found myself wishing I could’ve planted a  Sierra Juarez Piñon instead; it’s fine-looking tree (though it most likely wouldn’t handle a Salt Lake winter.) I enjoyed poking around along the ridge. Checking out a new pine is always fun- familiar yet new at the same time, another way of being a tree.

Sierra Juarez Piñon instead; it’s fine-looking tree (though it most likely wouldn’t handle a Salt Lake winter.) I enjoyed poking around along the ridge. Checking out a new pine is always fun- familiar yet new at the same time, another way of being a tree.

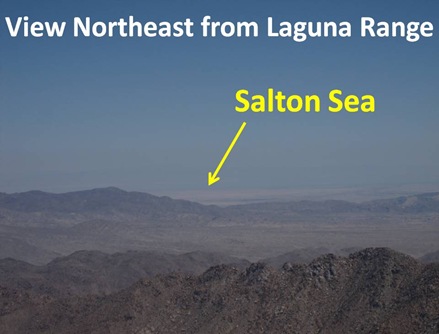

After I’d collected foliage and cones, I sat on a rock overlooking the desert to the East, drinking water and eating a scone. The land rolled down into the driest-looking desert imaginable, presented in a series of craggy peaks and valleys. In the far distance to the East-Northeast, a band of blue stood out- the Salton Sea.

Though I’ve passed within 40 or 50 miles of it and flown over it many times, I’ve never yet made it to the shores of this bizarre little “sea.” The Salton Sea is a saline rift lake, meaning that occupies a rift valley, which is defined as the valley formed along a geologic fault- in this case the San Andreas Fault. The lowest part of this valley is the Salton Sink, whose floor (now submerged) lies roughly 280 feet below sea level. Over the past 3 million years, the lowest reaches of the Colorado River have changed course and the location of its delta several times, eventually creating a dam of sorts that separates the valley from the Sea of Cortez. During this time the Salton Sink has alternately been both a freshwater lake and a dry empty basin repeatedly.

Though I’ve passed within 40 or 50 miles of it and flown over it many times, I’ve never yet made it to the shores of this bizarre little “sea.” The Salton Sea is a saline rift lake, meaning that occupies a rift valley, which is defined as the valley formed along a geologic fault- in this case the San Andreas Fault. The lowest part of this valley is the Salton Sink, whose floor (now submerged) lies roughly 280 feet below sea level. Over the past 3 million years, the lowest reaches of the Colorado River have changed course and the location of its delta several times, eventually creating a dam of sorts that separates the valley from the Sea of Cortez. During this time the Salton Sink has alternately been both a freshwater lake and a dry empty basin repeatedly.

When Europeans arrived, the Sink was empty. But in 1905 heavy rainfall and snowmelt caused a dike to breach in the Imperial Valley. It took nearly 2 years to get the river back under control, and during that time, the Salton Sea- California’s largest lake- was formed. The sea is broad and shallow (max depth = ~50 feet), and has no outlet except for evaporation. Over the past century, its salinity has increased dramatically. Back in the 1930s, 40s and 50s the sea supported several species of introduced fish, but today, with the rising salinity, Tilapia survives, but not much else.

Broad, shallow and saline, the sea is strikingly similar to my own Great Salt Lake, and I hope to make it to its shores one of these years, both for the novelty of its waters as well as its bizarrely low altitude.

I returned to the car and headed back West to the ocean, the haze and my job. Soon I was busy at work, greeting clients and colleagues. 2 days later, tired and stressed, I stopped by my room quickly to grab a folder. On a whim I dug the ziplock baggie full of cones and foliage out of my suitcase, unzipped it and took a deep, piney sniff. For a moment I was back in the clear hot sky at 6,000 feet, the Salton Sea hovering far below in the distance. I closed the baggie and went back to work.

I returned to the car and headed back West to the ocean, the haze and my job. Soon I was busy at work, greeting clients and colleagues. 2 days later, tired and stressed, I stopped by my room quickly to grab a folder. On a whim I dug the ziplock baggie full of cones and foliage out of my suitcase, unzipped it and took a deep, piney sniff. For a moment I was back in the clear hot sky at 6,000 feet, the Salton Sea hovering far below in the distance. I closed the baggie and went back to work.