From our camp at the junction of Tuckup and

Arizona Steve ascended first. As I followed, I could see that the sidehill placed us at the base of a second, higher pour-off that was recessed into an alcove, which Steve had already detoured into. As I paused scanning for a route on up, he called for me to come check it out. The alcove was fronted by a stand of small cottonwoods, behind which lay a pool backed by a wonderful hanging garden.

All About Hanging Gardens

Hanging gardens occur across the Colorado Plateau where continual seeps of water emerge from rock/cliff walls, creating little oases of moisture, and often shade, which support a community of plants quite different from the surrounding desert.

*That time of course varies by the size, depth and aspect of the pocket. Exceptionally large/deep pockets are known as “tanks” and are often year-round effective water sources.

But the rock layers are full of cracks and crevices, and some portion of rainwater trickles down into these

Often this happens when the water encounters less permeable rock below, such as less fragmented/porous rock or a layer of shale, and is forced sideways. In canyon country a likely place for this to happen is at the interface of 2 distinct geologic layers. Further North in Southern Utah, this often happens where the Navajo and Kayenta formations meet. Down here in the Grand Canyon, those younger layers are nowhere to be seen, and so the Cottonwood Canyon alcove-garden, which is also a transition-layer garden, occurs among very different- and older- rock layers.

*For non-geology-minded Utah mountain bikers: Navajo is what you’re rolling across on Moab’s Slickrock Trail. Entrada is what you’re “surfing” up at Bartlett Wash. I did a geology-mtn biking post early this down around Gooseberry Mesa, but would love to do a broader mtb-geology post across Southern Utah. We’ll see.

When I learned this, I thought about my absolute favorite hanging garden, at the head of Twin Corral Box Canyon, which I will describe further on down in the post. Twin Corral Box, when you hike into it from the Dirty Devil, is walled with massive Wingate cliffs. But at its upper end, higher up, the cliffs are Navajo. Higher up-stream on the Dirty Devil BTW, the side canyons are overwhelmingly Navajo-walled, and as a result many of them, like the Robber’s Roost system, host wonderful hanging gardens all over the place. (One of the most rewarding things about this whole project has been the numerous ah-ha! moments when something I noticed years ago suddenly makes sense…)

Immediately above the garden is the bottom of the Redwall Formation, which we looked at in the last post. Our hike led us up through the Muav, but in between appeared a narrow and very different layer, which I believe was the Temple Butte Formation (and which I’ll describe later in the post.)

Floor

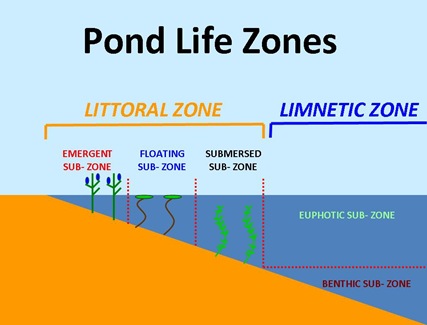

An alcove-hanging-garden- which is a specific type of hanging garden- supports an array of plants roughly divided into 3 zones. At the bottom of the alcove, by the base of the wall and often alongside a pool, are the most “normal” plants, by which I mean plants that root in soil and grow upwards. The soil is formed very gradually from fragments of the collapsing rock wall. Because the soil is limited and forms so slowly, alcove-gardens are fragile places. If the limited soil gets excessively trampled, peed/pooped in/on or otherwise abused, the plants community in this bottom layer can be disrupted or destroyed. (Exotics- like Tamarisk or Ravenna Grass, Saccharum ravennae, can also mess up this zone.)

Wall

The middle zone is the “wall” zone, up against the flat, damp, soil-less vertical rock wall of the alcove, and this zone supports mainly algae and cyanobacteria.

Most of the algae species that live on alcove walls are not endemic to that environment, meaning that most occur also in other environments. In a study in the late 1980s roughly 204 species of algae were found on Utah hanging garden walls, out of ~1,900 known statewide*. Of those 204, only 16 were not known to occur in any other environment than hanging gardens.

*I don’t know if this number has increased significantly since then.

Like Green Algae, Golden Algae are generally teeny-tiny photosynthetic creatures, but they’re not at all closely-related to them. In fact they’re likely about as distantly-related to Green Algae as we are. The systematics of these guys are still unsettled (and the group itself appears to be polyphyletic), but it now appears that they belong to a completely separate kingdom, the Chromists, Chromista*, which includes Brown Algae, Yellow-Green Algae and Diatoms, in addition to a few other things you never heard of.

*Way unsettled. In the 2005, an alternative kingdom, Chromolveolata, was proposed, and then in 2008 it was proposed that this group be split into 2 kingdoms. I can’t keep up. In any case, they’re way, way different from Green Algae, and they’re most certainly not plants.

Tangent: This is what is so cool about life at the microscopic level. Up here on the giganto-macro level where we reside, we perceive only a little fraction of the diversity of living things. The “kingdoms” or “kinds of living things that we can see and touch- animals, plants and fungi- appear to be just 3 of 6, 7, or maybe 11(?) kingdoms of eukaryotic creatures. And then of course there are the kazillions of prokaryotes…

Most of the time, most Golden Algae species behave more or less like Green Algae- sitting around, mostly in damp/wet places, and photosynthesizing. But here’s something cool about many of them: when deprived of light, or when they find themselves in the presence of abundant alternative food, they can switch to a predatory mode, feeding upon bacteria and diatoms. Golden Algae are sort of like little alternate-universe plants that can turn suddenly and opportunistically carnivorous.

Ceiling

The common plant at the seep zone is Maidenhair Fern, genus = Adantium.

*I covered the basics of Ferns, and their freaky-cool haploid-diploid generational pattern last year down in Costa Rica. Man, it is like I have a post for everything.

Another seep-zone plant was in flower. When it first caught my eye I thought it some type of Gilia,

*Sorry- for some reason I only snapped this one rather low-quality shot. I have no excuse except that I take lots of photos when I hike, and don’t really know at the time what- if anything- I’ll blog about.

Tangent: I say “supposedly” because I can’t count how many plants I’ve read about that Indians allegedly used to treat syphilis. Seriously, it has to be dozens. What I wonder is whether any of these plants actually eased the symptoms of the disease (certainly none of them cured it) or whether the Indians were just so desperate that they pretty much tried anything. And in fairness, Syphilis appears to have been a much more virulent (and horrible) disease during its first recorded few decades in Europe than it was by the later 16th century, by which time it was basically the disease it is today.

Syphilis BTW has a fascinating and still unsettled history. For a long time, it was cited as a classic example of a New World disease spreading to the Old World. But other researchers believe that it was already present in both New and Old Worlds. Still other researchers hypothesize that it evolved in the Old World, was carried across the Beringian land-bridge with Paleo-Indians, and then re-encountered by European explorer. The timing of the disease’s history in Europe is tricky; the first major outbreak was in 1494, which would mean that if it was a New World pathogen, it pretty much would have had to arrive in Europe via Columbus’ first voyage.

Nested Tangent: I sometimes pick up a tone of explanation or justification in traditional New-World-Origin accounts of Syphilis. Yes, we gave the Indians Smallpox and a whole bunch of other diseases, the story goes, but hey, they gave us syphilis, as though it somehow balances things out.

Today in the age of AIDS, syphilis is farther down on the list of most folks’ STD-worries, yet another of the multitude of terrible diseases that’s largely been beaten in the First World, allowing so many more of us to live long enough to succumb to cancer. I wonder, if they ever cure cancer, what we will start dying of next?*

*I’m reminded of the old Red Foxx line (paraphrasing): “All these health nuts are going to feel stupid someday, lying in a hospital bed, dying of nothing.”

Scarlet Lobelia’s medicinal properties- whatever they are- likely are a result of the plant’s alkaloids, which can be toxic, and probably shouldn’t be messed with. BTW, you won’t find this flower in hanging gardens up around Moab or Canyonlands; though it’s common in them around the Grand Canyon, Glen Canyon NRA and Zion, it doesn’t appear in hanging gardens further North.

Alcove hanging gardens always seem quiet, contemplative places. When I’m in one I always feel as though I should speak softly and be respectful somehow. I don’t know that this feeling stems from any karmic-greenie Earth-vine or anything, so much as they half-consciously remind me of cathedrals, with their dim light, still, cool air and vaulted ceilings. The Cotton Canyon Alcove is small- maybe 30 feet high, but I’ve stood in others that are huge. The side canyons of the Dirty Devil in particular contain a number of spectacular ones, the largest and most amazing of which lies at the head of Twin Corral Box Canyon, with a ceiling of well over 100 feet high.

Tangent: Yes, I backpack with a wristwatch. I do almost everything with a wristwatch. Once on a trip along the Dirty Devil about a decade ago, Steve and I decided we wouldn’t bring a watch. After all, we were backpacking, we had all day, why be constrained by something so civilized as a watch? Why not wake when it gets light and go to sleep when it turns dark? Isn’t that the right, “natural” way to live?

It turned out to be a terrible idea. The trip was in October- a time of shortening days- and we spent most of the trip in deep-walled canyons under overcast skies. We never could never tell what time it was, and as we didn’t want to get stranded out day-hiking away from our base camp after nightfall, we really needed to know what time it was. As a result, we must have asked OCRick- who accompanied us on the trip but abstained form our little back-to-nature-wristwatch-rebellion- the time at least 30 times a day.

Continuing up around and above the alcove was the only tricky part of the hike, involving an exposed scramble up a series of ledges on the North side. Fortunately the rock of these ledges was distinctly different from that below or above- an extremely rough-surface, abrasive stone that was wonderful for free-climbing*. I’m pretty sure this was the Temple Butte Formation, a relatively narrow band between the Muav and the Redwall, that tends to be thicker in the West End of the Grand Canyon**.

*But would be awful to fall or slide on.

**And which I either missed (entirely possible, as this geology stuff is still pretty new to me) or is absent in the main drainage of Tuckup Canyon.

***Different sources give really different ages for this layer.

*There’s a bolt at the top of the alcove. Rappelling down would be easier and safer than the ledgy down-climb

**This, BTW, is why hiking narrow canyons is so great to do with kids. The constant surprise-around-every-corner aspect and frequent scrambling opportunities distract them from the mundane-ness of trudging along for hours.

*Which I described in Part 2 of this series.

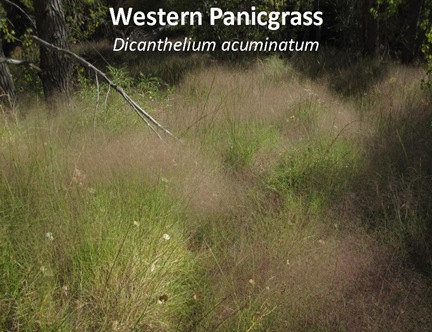

The ground all around the spring was damp and grassy, and the grass here had a strange appearance, almost hazy, as though you couldn’t focus on it. On closer examination the “haze” was an abundance of super-fine stalks bearing seeds, like nothing I was familiar with.

Next Up: The River.

Note About Sources: Geologic info for this post came primarily from Bob Ribokas’ Grand Canyon Explorer site, Stephen R. Whitney’s A Field Guide to the Grand Canyon and Wikipedia. Hanging Garden Info came from David Williams’ A Naturalist’s Guide to Canyon Country, and On The Distribution of Utah’s Hanging Gardens, Stanley L. Welsh, from the Great Basin Naturalist*. Welsh’s paper provided the algal species distribution info, but was apparently published before(?) the classification of Chrysophyta as Golden Algae, for which my primary source was the University of California Museum of Paleontology site. Panicgrass info came from the Master’s thesis, A Morphological Invesitagtion of Dicanthelium Section Lanuginosa (Poaceae), Justin Ray Thomas, Miami University.

*Now the Western North American Naturalist. Man, there is like a publication for everything.