Sometimes, right before bed, I find all of a sudden that I’m really thirsty. Somehow over the last couple of hours I suddenly realize that I haven’t drunk anything in a while. But when I drink water, it doesn’t seem to slake my thirst, and no matter how much I drink, I still feel thirsty until I drink something sweet, like orange juice or a glass of Gatorade.

That’s sort of the same feeling I get this time of year when I go a few days without seeing something green. Not dark, almost black PLT-green, not dull olive green of Mountain Mahogany, and not the fading drab remnants of the few yet-to-shed leafy trees of the valley. I miss real, green. Bright, living, photosynthesizing green, and no matter how many pretty mountains or hills I look at, I’m still left thirsty for color.

The Mossy Wall

There’s one spot of color in the foothills that I visit several times a Fall/Winter. It’s 4.2 miles from my house by mtn bike, and I call it- imaginative fellow that I am- The Mossy Wall.

There’s one spot of color in the foothills that I visit several times a Fall/Winter. It’s 4.2 miles from my house by mtn bike, and I call it- imaginative fellow that I am- The Mossy Wall.

Since starting this blog, I must’ve blogged about, or at least mentioned, more than 100 different plants, both here in Utah, and in my travels further afield. And what all of them have had in common, the pines, the PLTs, the Redwoods, the Oaks and Maples and Bitterbrush and Creosote and Cycads, and Gingko and Mormon Tea and all the rest, is this: they are all Tracheophytes, or vascular plants.

The evolution of a vascular system, of xylem and phloem, was probably the 3rd-most significant evolutionary step in the history of plants (the 1st being chlorophyll, the 2nd being the symbiotic evolution of chloroplasts and cyanobacteria.) It made trees, shrubs, flowers, grasses and fruits all possible. But to watch through world through only vascular plants is to ignore the other 3 great divisions of land plants: the liverworts, hornworts and mosses. Of these, the mosses are the most common and numerous, with an estimated 20,000 species, making them second only to angiosperms in diversity.

The evolution of a vascular system, of xylem and phloem, was probably the 3rd-most significant evolutionary step in the history of plants (the 1st being chlorophyll, the 2nd being the symbiotic evolution of chloroplasts and cyanobacteria.) It made trees, shrubs, flowers, grasses and fruits all possible. But to watch through world through only vascular plants is to ignore the other 3 great divisions of land plants: the liverworts, hornworts and mosses. Of these, the mosses are the most common and numerous, with an estimated 20,000 species, making them second only to angiosperms in diversity.

Tangent: In a lot of “plant family tree” charts, liverworts, hornworts and mosses are lumped together, apart from the Tracheophytes. This isn’t quite accurate, as there’s not really any evidence that the 3 comprise a monophyletic group, or are more closely related to each other than any one of the 3 is related to the Tracheophytes.

Mosses, or Bryophytes, are divided into 6 classes. One of those classes, Sphagnipsoda, includes just 2 genera, one of which is Sphagnum, or Peat Moss. The Mossy Wall moss is peat moss. There are a couple hundred species of peat moss worldwide, and unless you’re a bryologist, well… forget about IDing the species. Mosses are notoriously hard to ID, and many can’t even be identified by a bryologist (yes, there are people who apparently make a living study mosses. How do I get that job?) using a hand lens! So I’ll settle for the genus.

Mosses have no xylem, no phloem, and no roots. They attach to rock, soil or other surfaces via gripping structures called rhizoids, which look like little roots, but don’t do any of the water or nutrient transport things that real roots do. They just grab and hold on, that’s it. Mosses don’t store water; they just live off of whatever water’s around at the time- rain, dew or snowmelt.

Mosses have no xylem, no phloem, and no roots. They attach to rock, soil or other surfaces via gripping structures called rhizoids, which look like little roots, but don’t do any of the water or nutrient transport things that real roots do. They just grab and hold on, that’s it. Mosses don’t store water; they just live off of whatever water’s around at the time- rain, dew or snowmelt.

The peat moss of the mossy wall is a wonderful lush luxuriant green year-round. It lies on a North-facing wall in a canyon bottom at 5,700 feet. The canyon-bed is ride-able (though technical) and as you pedal or hike your way up, you wind around one gray/brown leafless bend after another, until- BAM- you get hit with a blast of color, a mat of green that seems so weirdly, wonderfully out of season, and your eyes finally find the drink they’ve been thirsting for.

The peat moss of the mossy wall is a wonderful lush luxuriant green year-round. It lies on a North-facing wall in a canyon bottom at 5,700 feet. The canyon-bed is ride-able (though technical) and as you pedal or hike your way up, you wind around one gray/brown leafless bend after another, until- BAM- you get hit with a blast of color, a mat of green that seems so weirdly, wonderfully out of season, and your eyes finally find the drink they’ve been thirsting for.

I can never resist removing a glove and laying a hand on the soft carpet- the only natural, soft thing in the dead of winter for miles around. The touch and the sight warm my heart against the color-less cold of a Wasatch winter.

I can never resist removing a glove and laying a hand on the soft carpet- the only natural, soft thing in the dead of winter for miles around. The touch and the sight warm my heart against the color-less cold of a Wasatch winter.

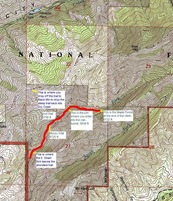

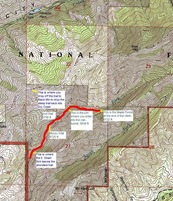

Tangent- Location: The Mossy Wall is located in the bottom of Dry Creek Canyon, but ½ mile above where the Bonneville Shoreline Trail (BST) turns way to the West and climbs out of the canyon bottom. Though not an official trail, it gets ridden and hiked for close to a mile up pretty regularly. This “trail” as it were, became somewhat better known after the 2003 rescue of Elizabeth Smart as it leads to the primary initial campsite of her abductors. Many locals know it as the “Elizabeth Smart Trail.”

Tangent- Location: The Mossy Wall is located in the bottom of Dry Creek Canyon, but ½ mile above where the Bonneville Shoreline Trail (BST) turns way to the West and climbs out of the canyon bottom. Though not an official trail, it gets ridden and hiked for close to a mile up pretty regularly. This “trail” as it were, became somewhat better known after the 2003 rescue of Elizabeth Smart as it leads to the primary initial campsite of her abductors. Many locals know it as the “Elizabeth Smart Trail.”

I mentioned this route in a previous post, when describing the location of my favorite Bigtooth Maple Grove, which lies 1.5 miles up-canyon from the BST junction. Alas, when I last attempted the uppermost ½ mile in the Fall of 2007, I found it hopelessly overgrown for a mountain bike.

The First Cool Thing About Moss

So why does moss stay green all winter long when everything else around is brown? The answer is their simplified architecture. Most flowering plants can only perform photosynthesis with a net gain in energy at temperatures down to around 50F. Much below 50F, and the demands of producing and moving the sugars around inside burn more energy than is produced by photosynthesis, and this is the reason why most flowering plants stay dormant in the winter.

Tangent: There are a number of early-blooming wildflowers, such as Glacier Lilies, that grow and bloom even before the snowmelt, but these plants are using stored energy reserves from the previous year. Even conifers, such as PLTs, don’t photosynthesize during most of the winter, though their evergreen needles allow them to do so opportunistically during warm spells.

But without a complex vascular system to support and modulate, mosses can photosynthesize with a net energy gain at temperatures down to just above freezing, and that’s why it maintains its lush green color throughout the winter.

But without a complex vascular system to support and modulate, mosses can photosynthesize with a net energy gain at temperatures down to just above freezing, and that’s why it maintains its lush green color throughout the winter.

The Second Cool Thing About Moss

But the really weird thing about Moss is its genetics and reproductive strategy, which is way, way different from that of tracheophytes or anything else we’ve looked at.

Mosses exhibit a characteristic called Haploid Dominance, which means that in its “dominant” state, or the way we most often encounter it, it is haploid, having just 1 set of chromosomes. But it reproduces via alternating haploid and fully diploid generations, meaning that a haploid parent produces a diploid offspring, which in turn produces haploid offspring and so on and so on… So in other words, when you look at moss, here’s what’s going on:

The peat moss on the Mossy Wall is haploid, meaning that each cell contains only 1 set of chromosomes, which in Sphagnum is 19 chromosomes. The haploid generation is called the Gametophyte generation, and it is this generation that performs photosynthesis. Mosses in the haploid state can either be male, female, or both. The male organs, called antheridia, occur on different stems (yes moss has zillions of little stems) from the female organs, which are called archegonia.

Mosses never evolved pollen; they reproduce via sperm and eggs. Each sperm or egg cell is also haploid, and therefore each one contains all 19 chromosomes of the moss producing it. Pollen was another wonderful evolutionary step in tracheophytes; it enabled the dispersal of genetic material for many miles from the parent. But moss-sperm travel the old-fashioned way: they swim (like animal sperm) and this means that mosses can only mate with very close/adjacent mosses and they can only do so when wet.

Mosses never evolved pollen; they reproduce via sperm and eggs. Each sperm or egg cell is also haploid, and therefore each one contains all 19 chromosomes of the moss producing it. Pollen was another wonderful evolutionary step in tracheophytes; it enabled the dispersal of genetic material for many miles from the parent. But moss-sperm travel the old-fashioned way: they swim (like animal sperm) and this means that mosses can only mate with very close/adjacent mosses and they can only do so when wet.

When egg and sperm do successfully meet up they unite to create a single, fully diploid (38 chromosomes), cell which grows into a fully diploid moss called a Sporophyte. A sporophyte doesn’t expand or photosynthesize, and in fact it lives its whole life attached parasitically to its “mother”. Sporophytes do one thing, which is to create (via meiosis) and disperse haploid spores. The spores are borne at the end of tall (relative to moss that is) stalks and carried away by the wind. Ideally some of the spores land in suitable locations for moss growth and then develop into an new, haploid, gametophyte generation. Mosses also reproduce clonally, or vegetatively, like so many other plants, and such reproduction represents simply a continuation of the haploid gametophyte.

When egg and sperm do successfully meet up they unite to create a single, fully diploid (38 chromosomes), cell which grows into a fully diploid moss called a Sporophyte. A sporophyte doesn’t expand or photosynthesize, and in fact it lives its whole life attached parasitically to its “mother”. Sporophytes do one thing, which is to create (via meiosis) and disperse haploid spores. The spores are borne at the end of tall (relative to moss that is) stalks and carried away by the wind. Ideally some of the spores land in suitable locations for moss growth and then develop into an new, haploid, gametophyte generation. Mosses also reproduce clonally, or vegetatively, like so many other plants, and such reproduction represents simply a continuation of the haploid gametophyte.

Mosses are way more common in wetter climes. I used to see them all over the place in New England and of course they’re everywhere in the Pacific Northwest. But this relative rarity of extensive mossy areas here in the Intermountain West somehow makes them more amazing and wonderful- isolated patches of soft, living, breathing green in the midst of the cold, dead desert winter. Over the years I’ve come to think of the Mossy Wall as an old friend that helps to focus and encourage me, reminding me of the living year to come.

Mosses are way more common in wetter climes. I used to see them all over the place in New England and of course they’re everywhere in the Pacific Northwest. But this relative rarity of extensive mossy areas here in the Intermountain West somehow makes them more amazing and wonderful- isolated patches of soft, living, breathing green in the midst of the cold, dead desert winter. Over the years I’ve come to think of the Mossy Wall as an old friend that helps to focus and encourage me, reminding me of the living year to come.

14 comments:

Phew! Thanks for the alternative reading, Alex.

Wow. I think we've been separated at birth. I blog about bike riding and tangent all the time about plants.

Awesome stuff!!

Jenni- I think we *are* separated at birth! I spent some time over on your blog and see we've even both done posts about about the phytophotodermatitis- causing sap of Heracleum (our species here is "maximum.") It's great to find another cyclist/botanist, and I look forward to following your blog. As an aside I think you'd also really enjoy "Foothill Fancies" (on my blogroll.)

I'll follow your suggestion and darken the links color- thanks. And BTW, when I clicked on your profile photo, my 1st thought was, "Floyd Landis' wife reads my blog? How cool is this?"

Oh dear, Alex, I hate to burst your capsule, but it's not Sphagnum. That doesn't mean (moss expert I'm not) that I can identify this one, but not peat, at any rate. Peat, as in bogs, is almost aquatic and unlikely to be found on a wall. Usually acid. Etc.

From your description on your bike ride, I thought it might be a Selaginella, but now I can't be sure. I'll try to send photos--or a post!

Try Sphag photo here versus Selag photo here, but not the right species. You have different ones that we do--but check S. underwoodii, S. utah.

Better yet (photowise) but still the wrong species: scroll to Sand Spikemoss, down past all the lycopods.

SLW, you're not bursting my capsule! And I so appreciate your trying to ID my mystery mosses. But re:the mossy wall near my house, you're confident then that it's a spikemoss and not a bryophyte? I didn't suspect a spikemoss before because I thought the "leafy-heads" of a spikemoss would be more prominent/bigger, but if you're sure then I'll zero in on those...

Thanks! -Alex

SLW- OK now I’m thinking you’re right about Selaginella. For the Mossy Wall, up by my house, S. watsonii, densa, underwoodii (barely) or mutica all look like possible range-matches. Check out this photo of S. watsonii and compare to my closeup? Here’s the range map, which would make this a possible candidate for the one down on Guacamole (SW UT) as well… WDYT? These guys are cool- makes me want to do a lycophyte post!

Looks good, if it's green enough for you. Densa is almost everywhere here, likes it dry and is mostly brown most of the time. We have underwoodii and mutica here, but I'm not sure I've seen them. Our S. weatherbiana is a big thick green one, likes cliffs and drippy spots... Texture of these should be a little coarser, I'd think, than the mosses. Looks like you're on to something. Check out internet resources at the abls.org site... maybe they've got some photos or keys. Good luck!

Sally

Oh, and if it's Selaginella, those terete tips (as in the watsoni photos) are where the sporangia are; in the axils of the leaves.

And, while I agree these guys are way cool, they are not lycophytes (or lycopods, more often called).

You are really challenging me here, to dig back into my memory bank and refresh my limited knowledge. Great fun! I'll work on a post soon.

Thanks,

Sally

OK, let me know what you come up with. I got the impression Selaginella was a LycoPHYTE (division Lycopodiophyta) but not a LycoPOD(?) (class Lycopodiopsida). I was going off

this, this, this, this and this.

(Phew! That's a lot on taxono-surfing!)

Okay-- should have refreshed first! Or should know better than to tangle with someone who is keeping up with current stuff. Honestly, I don't think I'd heard the word "lycophyte" before--shows you how out-of-date I am. They have changed things, even among 350-million-year-old plants!

Ah well, c'est la vie. Just know that you can't trust me, eh?

Sally- no worries. I really, really appreciate all the time and effort you've been spending helping me out, and your catch on the "moss" has keyed me into a whole new interesting group of plants. Thanks so much!

-Alex

Post a Comment