I’ve blogged previously about how clueless I was about trees until a couple of years ago, and the sad truth was that I was even more clueless about birds until even more recently- like the past year or so. But over the past year I’ve gradually learned to recognize the birds at our feeder.

Tangent: And I should give credit where credit’s due- to the Bird Whisperer. Over the past year, while I’ve been in the kitchen or family room and spotted a bird I didn’t recognize at the feeder, I must have yelled, “Hey [HIS NAME], get over here, I need a bird ID!” at least 80 times, and every time the little guy has dropped whatever he was doing, reading or watching- Yugi-Oh!, dinosaurs, sharks, Bigfoot-related web sites- and run over to help me out. He is a wonderful kid, and I could not be a happier or prouder father.

Tangent: And I should give credit where credit’s due- to the Bird Whisperer. Over the past year, while I’ve been in the kitchen or family room and spotted a bird I didn’t recognize at the feeder, I must have yelled, “Hey [HIS NAME], get over here, I need a bird ID!” at least 80 times, and every time the little guy has dropped whatever he was doing, reading or watching- Yugi-Oh!, dinosaurs, sharks, Bigfoot-related web sites- and run over to help me out. He is a wonderful kid, and I could not be a happier or prouder father.

And probably the first I learned to recognize, and by far the most common, is the House Finch, Carpodacus mexicanus. (pic left) The House Finch isn’t a particularly large, glamorous, or (at all) unusual bird; if you live in the US and have a feeder in your yard, you probably see them all the time. And so quickly I became pretty blasé about seeing House Finches; out of the corner of my eye, I’d see movement of the feeder, turn and look, think, “Oh, House Finch…” and turn away.

And probably the first I learned to recognize, and by far the most common, is the House Finch, Carpodacus mexicanus. (pic left) The House Finch isn’t a particularly large, glamorous, or (at all) unusual bird; if you live in the US and have a feeder in your yard, you probably see them all the time. And so quickly I became pretty blasé about seeing House Finches; out of the corner of my eye, I’d see movement of the feeder, turn and look, think, “Oh, House Finch…” and turn away.

But then about a month or so ago, I spent a few hours learning what I could about them, and now I don’t turn away so quickly. Today’s post and the next post are all about this guy, the star of my feeder, and if you hang with me, maybe you won’t turn away so quickly the next time you see him either.

The genus Carpodacus is commonly called the Rose Finches and includes 2 dozen species across the Northern hemisphere, but only 3 here in North America: The House Finch, the Purple Finch, C. purpereus- which is native mainly to the Northeastern US and Southeastern Canada (but also strangely has a distinct subspecies population out in California) - and Cassin’s Finch, C. Cassinii (pic right)- which is native to the Western US and Canada, is also resident year-round in Utah, and looks a lot like a House Finch, but bigger.

The genus Carpodacus is commonly called the Rose Finches and includes 2 dozen species across the Northern hemisphere, but only 3 here in North America: The House Finch, the Purple Finch, C. purpereus- which is native mainly to the Northeastern US and Southeastern Canada (but also strangely has a distinct subspecies population out in California) - and Cassin’s Finch, C. Cassinii (pic right)- which is native to the Western US and Canada, is also resident year-round in Utah, and looks a lot like a House Finch, but bigger.

Male House Finches have a red breast and head. (pic left, male on right, female left) (I’ve read that they can also have yellow head and breast, but I’ve seen only red in our yard.) The red pigment isn’t produced by the bird, but rather obtained from food eaten while in molt. (We looked at another bird- the Western Tanager- that also obtains red feather-pigments via diet, last Spring.) Females are attracted to the males with the reddest head/breast feathers, and so the red coloring may act as a “fitness” indicator, signaling that the male is an effective forager. House Finches are seed-eaters, eating only the occasional aphid along with seeds. (Remember this- we’ll come back to it in the next post.) They love Dandelion seeds and are suckers for Sunflower seeds in feeders.

Male House Finches have a red breast and head. (pic left, male on right, female left) (I’ve read that they can also have yellow head and breast, but I’ve seen only red in our yard.) The red pigment isn’t produced by the bird, but rather obtained from food eaten while in molt. (We looked at another bird- the Western Tanager- that also obtains red feather-pigments via diet, last Spring.) Females are attracted to the males with the reddest head/breast feathers, and so the red coloring may act as a “fitness” indicator, signaling that the male is an effective forager. House Finches are seed-eaters, eating only the occasional aphid along with seeds. (Remember this- we’ll come back to it in the next post.) They love Dandelion seeds and are suckers for Sunflower seeds in feeders.

House Finches are found all over the US, but are actually only native to the Western US. Around 1940, they were apparently released in Long Island, and quickly became naturalized and spread throughout the Eastern US. I’ve found a few different variants of the story of this introduction, and have chosen the most dramatic to tell here: Supposedly in 1940, an unscrupulous bird dealer in Long Island was selling House Finches illegally, as “Hollywood Finches”. Tipped off that police were on the way to bust him, he released his entire stock of House Finches, which founded the Eastern population.

House Finches are found all over the US, but are actually only native to the Western US. Around 1940, they were apparently released in Long Island, and quickly became naturalized and spread throughout the Eastern US. I’ve found a few different variants of the story of this introduction, and have chosen the most dramatic to tell here: Supposedly in 1940, an unscrupulous bird dealer in Long Island was selling House Finches illegally, as “Hollywood Finches”. Tipped off that police were on the way to bust him, he released his entire stock of House Finches, which founded the Eastern population.

Tangent: As wonderfully exciting as this story sounds, I think it reeks of urban legend, with a plotline that seems a strange amalgam of Midnight Express and the Aeneid. I think it’s likelier they just weren’t selling (they’re not terribly spectacular birds…) and one or more pet shop owners released them, and/or successive pet owner released them over a number of years…

However they were introduced, they spread quickly, and as they’ve done so they’ve had a big negative impact on the native Purple Finches. (pic left, male on left, female right) The 2 species seek similar foods and nesting sites, and so compete for territory. The House Finch is the more aggressive species, and so when the 2 scrap, the Purple Finch almost always is the one to withdraw/back down.

However they were introduced, they spread quickly, and as they’ve done so they’ve had a big negative impact on the native Purple Finches. (pic left, male on left, female right) The 2 species seek similar foods and nesting sites, and so compete for territory. The House Finch is the more aggressive species, and so when the 2 scrap, the Purple Finch almost always is the one to withdraw/back down.

Tangent: The Purple Finch has, unfortunately, suffered somewhat of a double-whammy as a result of human introductions. Almost a century before the House Finch appeared on the East Coast, the introduction of the European House Sparrow, Passer domesticus, caused a similar, earlier disruption in Purple Finch range and population.

Revenge of the Purple Finch

But after half a century in its expanded range, the House Finch met its own challenge. In the mid 1990’s East Coast House Finch populations started to decline dramatically, as a result of a virulent strain of eye conjunctivitis. There are several causes of eye conjunctivitis (think Pink-Eye) in birds, including bacteria, fungi and viruses. The causative agent in this case is a bacterium, Mycoplasma gallisepticum (MG). MG has long been a scourge of domestic chickens and turkeys, and it’s thought that a new strain evolved in the 90’s that was able to infect the House Finch. Infected birds display scabby, runny or cloudy eyes. The disease can blind the Finches, causing them to starve.

There are several causes of eye conjunctivitis (think Pink-Eye) in birds, including bacteria, fungi and viruses. The causative agent in this case is a bacterium, Mycoplasma gallisepticum (MG). MG has long been a scourge of domestic chickens and turkeys, and it’s thought that a new strain evolved in the 90’s that was able to infect the House Finch. Infected birds display scabby, runny or cloudy eyes. The disease can blind the Finches, causing them to starve.

Side Note: Mycoplasma is a genus of about 100 known species of bacteria. One of the other species, M. pneumonia, is a cause of “walking pneumonia” in humans. Mycoplasma is an interesting genus in that it lacks a cell wall, and instead utilizes a type of organic molecule called sterols that it obtains from its host to stabilize its outer membrane. In humans the most commonly used sterol is cholesterol (diagram right).

Side Note: Mycoplasma is a genus of about 100 known species of bacteria. One of the other species, M. pneumonia, is a cause of “walking pneumonia” in humans. Mycoplasma is an interesting genus in that it lacks a cell wall, and instead utilizes a type of organic molecule called sterols that it obtains from its host to stabilize its outer membrane. In humans the most commonly used sterol is cholesterol (diagram right).

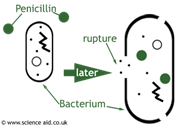

Now most antibiotics, including penicillin, fight bacteria by latching onto the cell wall of the bacterium in question, and then preventing that wall from growing new cells. As the bacterium continues to grow, the wall can’t keep up with it, and it weakens and ruptures, killing the bacterium. But because Mycoplasma lacks a cell wall, none of these “standard” (specifically beta-lactam) antibiotics work against it. For this reason, there was for many years confusion about the cause of M. pneumoniae-induced walking pneumonia, with many researchers believing it was caused by a virus.

Now most antibiotics, including penicillin, fight bacteria by latching onto the cell wall of the bacterium in question, and then preventing that wall from growing new cells. As the bacterium continues to grow, the wall can’t keep up with it, and it weakens and ruptures, killing the bacterium. But because Mycoplasma lacks a cell wall, none of these “standard” (specifically beta-lactam) antibiotics work against it. For this reason, there was for many years confusion about the cause of M. pneumoniae-induced walking pneumonia, with many researchers believing it was caused by a virus.

A possible aggravating factor may be the limited genetic variability of Eastern House Finches (pic left = sick female). Since they’re descended from a small founding population (whether from pet shop or no) all Eastern House Finches are pretty closely related. As a rule of thumb, populations of animals (or plants) with greater genetic diversity tend to do better when faced with disease, because there’s a higher likelihood that some individuals will have a bit more resistance to a specific disease, and those individuals will be a little likelier to survive and reproduce, thereby passing that resistance on to the next generation.

A possible aggravating factor may be the limited genetic variability of Eastern House Finches (pic left = sick female). Since they’re descended from a small founding population (whether from pet shop or no) all Eastern House Finches are pretty closely related. As a rule of thumb, populations of animals (or plants) with greater genetic diversity tend to do better when faced with disease, because there’s a higher likelihood that some individuals will have a bit more resistance to a specific disease, and those individuals will be a little likelier to survive and reproduce, thereby passing that resistance on to the next generation.

So far MG hasn’t appeared in the West, though its range is spreading and it’s now been found as far West as Michigan. MG isn’t expected to wipe out Eastern House Finches, but it’s reduced their numbers by somewhere around half, and may be giving the Purple Finch- which is also susceptible to MG, but not nearly as affected by the disease- bit of breathing room.

Tangent: In tests, the other bird that is both very susceptible to and highly affected by MG is the American Goldfinch, Carduelis tristis. But oddly, American Goldfinches in the East, which routinely visit the same feeders as House Finches (as they do in my yard) seem largely un-impacted by MG. Why this should be, and whether there’s some behavioral difference between the 2 species that facilitates transmission between House Finches more so than Goldfinches, is as yet unknown.

Tangent: In tests, the other bird that is both very susceptible to and highly affected by MG is the American Goldfinch, Carduelis tristis. But oddly, American Goldfinches in the East, which routinely visit the same feeders as House Finches (as they do in my yard) seem largely un-impacted by MG. Why this should be, and whether there’s some behavioral difference between the 2 species that facilitates transmission between House Finches more so than Goldfinches, is as yet unknown.

So the plain old House Finch isn’t so boring after all. But I’ve saved the most interesting thing about the House Finch for last.

Next Up: House Finches, Brood Parasites and Diet.

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteDo you ever think about doing some bird tagging? You can help contribute migratory data and you get to hold soft little birdies for a precious few seconds while you put their bands on.

ReplyDelete(Sorry reposted because I wanted to check that email follow up box!)

Jenni- it actually never occurred to me, but sounds like fun (and something I could maybe do with the Trifecta.) Have you done it? If so, I'd love any pointers to appropriate groups/ organizations. Thanks!

ReplyDeleteI really enjoyed the bird posts, particularly since you mentioned a couple of my favorites--chickadees and juncos. Birds are something I find interesting, although most of what I know about birds has to do with identification.

ReplyDeleteMaybe if I keep reading your blog I'll feel smarter about science. It's not something that comes naturally for me--there's a reason I was an English major.

Contacting your local Audubon Society would be the first step. I tagged for a bit at a local nature preserve, learned how to set the net up in front of a feeder and how to properly hold the birds, identify them, put their tags on and let them go. What an amazing feeling to hold those little guys up to your ear and listen to their hearts beat like tiny motors. I did this with children too, they loved it so much. (Except when the birds pooped in their hands of course, but hey...)

ReplyDeleteWhen I worked for the Nature Conservancy we used to do hawk migratory watching too- sit in a bird watch and just count how many flew overhead during certain times of the year. People get really jazzed about that, turns into a little party atmosphere. Ha, that's how us nature people party- what better way?

Jenni- thanks for the pointer. Sounds really cool, I'll check it out.

ReplyDeleteAndrea- you should know that probably 3/4 of what I write in this blog, I didn't know till I saw/noticed the thing in question, got interested, then found out everything I could about it. So if it makes you feel better, with most of this stuff I'm a neophyte too. (I have zero formal education in botany, ornithology, entomology, astronomy, hydrology, or pretty much any of the other things I write about.) Blogging about these things forces me to understand them, and that was the original motivation for starting the blog.