So to cap off Bird Feeder Week I’m blogging about what I think is the most interesting thing about the House Finch, and that’s its relationship with another bird, the Brown-Headed Cowbird.

Note to Birders: Of course, you already know all about the Brown-Headed Cowbird and its creepy, parasitic lifestyle. But unless you’re really on top of recent research, this post has a surprise ending, so stick with it.

The Brown-Headed Cowbird (BHC), Molothrus ater, (pic left, male) isn’t at my feeder, or anywhere around the Wasatch, right now. But it was here last summer (Bird Whisperer saw some down at Sugarhouse Park) and it’ll be back again in around 90 days or so. (The BHC isn’t a super-long-distance migrator. This time of year you can still find them down in AZ and NM.) What makes the BHC so darn interesting and horrifying at the same time is that it is a brood parasite.

The Brown-Headed Cowbird (BHC), Molothrus ater, (pic left, male) isn’t at my feeder, or anywhere around the Wasatch, right now. But it was here last summer (Bird Whisperer saw some down at Sugarhouse Park) and it’ll be back again in around 90 days or so. (The BHC isn’t a super-long-distance migrator. This time of year you can still find them down in AZ and NM.) What makes the BHC so darn interesting and horrifying at the same time is that it is a brood parasite.

A brood parasite is a bird that, instead of raising its own chicks, surreptitiously lays its eggs in the nest of another bird species, who then ideally (at least from the brood parasite’s perspective) rears the chick, which then matures, flies off, mates and repeats the cycle anew. Brood parasitic behavior has evolved independently multiple times, and there are about 80 known species of brood parasite birds in the world. The best known brood parasite is the Cuckoo, Cuculus canorus, (pic right) native to Eurasia and Africa. Here in the US, the BHC is by far the most common bird of this type.

A brood parasite is a bird that, instead of raising its own chicks, surreptitiously lays its eggs in the nest of another bird species, who then ideally (at least from the brood parasite’s perspective) rears the chick, which then matures, flies off, mates and repeats the cycle anew. Brood parasitic behavior has evolved independently multiple times, and there are about 80 known species of brood parasite birds in the world. The best known brood parasite is the Cuckoo, Cuculus canorus, (pic right) native to Eurasia and Africa. Here in the US, the BHC is by far the most common bird of this type.

Tangent: Guess what other critter has evolved brood parasitism? Bees. Such bees are called “Cuckoo Bees”, and they lay their eggs in the brood cells of other bee species. When they hatch, the larvae often kill and eat the host larvae cohabiting the brood cell. Brood parasitism in bees has apparently evolved separately dozens of times, and there are species that target solitary bees as well as others that target social bees. There are also brood parasitic wasps, who pull off the same trick with other wasp species. Which strikes me as kind of rich because of course the whole wasp reproductive “schtick” is parasitic, with different species parasitizing everything from acorns to caterpillars to figs to tarantulas. (To be accurate, the wasp “parasitism” of figs is more correctly mutualistic, in that Fig Wasps fertilize fig trees.) Oo- I feel a wasp post coming on next Spring… danger… danger… tangent getting too long… must return to topic at hand…

Tangent: Guess what other critter has evolved brood parasitism? Bees. Such bees are called “Cuckoo Bees”, and they lay their eggs in the brood cells of other bee species. When they hatch, the larvae often kill and eat the host larvae cohabiting the brood cell. Brood parasitism in bees has apparently evolved separately dozens of times, and there are species that target solitary bees as well as others that target social bees. There are also brood parasitic wasps, who pull off the same trick with other wasp species. Which strikes me as kind of rich because of course the whole wasp reproductive “schtick” is parasitic, with different species parasitizing everything from acorns to caterpillars to figs to tarantulas. (To be accurate, the wasp “parasitism” of figs is more correctly mutualistic, in that Fig Wasps fertilize fig trees.) Oo- I feel a wasp post coming on next Spring… danger… danger… tangent getting too long… must return to topic at hand…

Molothrus includes 5 species of Cowbird, all native to the Western hemisphere, and 3 of which, the BHC, the Bronzed Cowbird, M. aeneus, and the Shiny Cowbird, M. bonariensis, are native to the US. Of these, the BHC is far and away the most widespread. Pre-Euro-contact it was a bird of the Plains, following buffalo herds.  But with European settlement came cleared pasture/fields and domestic cattle, and its range has spread dramatically. This increase in range has had a disastrous effect on the populations of many species that traditionally had no contact with the BHC. The Kirtland Warbler, Dendroica kirtlandii, (pic below, right) in particular, which is native to Upper Michigan and Southern Ontario, faces possible extinction in the next couple of decades due in large part to the depredations of the BHC.

But with European settlement came cleared pasture/fields and domestic cattle, and its range has spread dramatically. This increase in range has had a disastrous effect on the populations of many species that traditionally had no contact with the BHC. The Kirtland Warbler, Dendroica kirtlandii, (pic below, right) in particular, which is native to Upper Michigan and Southern Ontario, faces possible extinction in the next couple of decades due in large part to the depredations of the BHC.

Different brood parasites have evolved different techniques for ensuring their eggs are accepted by the host species and that their young receive the lion’s share of food. Many brood parasites hatch more quickly than their host species. Others lay eggs that match the coloration and spotting pattern of targeted host species. Some brood parasites use a beak or hooked claw to destroy neighboring eggs as soon as they hatch. The Cuckoo hatches first, then pushes other eggs out of the nest.

Different brood parasites have evolved different techniques for ensuring their eggs are accepted by the host species and that their young receive the lion’s share of food. Many brood parasites hatch more quickly than their host species. Others lay eggs that match the coloration and spotting pattern of targeted host species. Some brood parasites use a beak or hooked claw to destroy neighboring eggs as soon as they hatch. The Cuckoo hatches first, then pushes other eggs out of the nest.

The BHC has 2 key adaptations that help make it successful. First, it lays eggs fast. A typical bird preyed upon by the BHC takes anywhere from 20 minutes to over an hour to lay a single egg. A female BHC lays an egg in under a minute. BHCs are prolific breeders; females lay up to 40 eggs per year, and both males and females typically mate with several different birds in a single season.

Tangent: When I wrote that last section, I had to refrain from making a snarky comment about the BHC. We tend to think of birds in positive, family-centric terms: monogamous, building nests together, caring for their young. But the BHC brushes aside all these stereotypes: It’s deceitful, abandons its young to a foster-nest, and is promiscuous to boot. From a human perspective, it’s hard to warm up to this bird. But when I blog about critters like Weevils or Black Widows and Rattlesnakes, I have to remind myself that they’re not us, and if I try to judge them as “little people” I’ll be continually disappointed.

Second, the BHC (pic left, female) is versatile; it parasitizes the nest of a whopping 240 different bird species, far and away the most of any brood parasite. By comparison, the Cuckoo parasitizes 130 species, and some brood parasites parasitize just a single species.

Second, the BHC (pic left, female) is versatile; it parasitizes the nest of a whopping 240 different bird species, far and away the most of any brood parasite. By comparison, the Cuckoo parasitizes 130 species, and some brood parasites parasitize just a single species.

Side Note: To make things a bit more complicated, most individual BHC females focus on just one target species, although many females are much more indiscriminate and target lots of species.

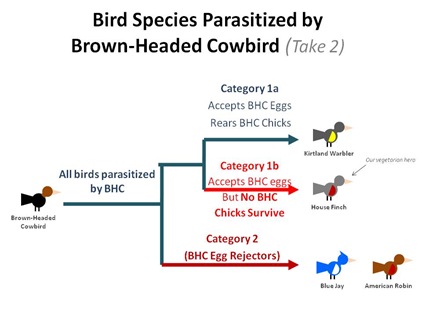

But what’s interesting about this versatility is that the BHC does not successfully parasitize 240 species. Out of those 240, a known 96, including the Blue Jay and the American Robin, reject the eggs outright, destroying them and/or chucking them overboard as soon as they return to the nest. The remaining 144 species are apparently fooled, accept the BHC eggs, incubate them and rear the chicks after hatching.

Tangent: Or maybe not… there’s another, controversial hypothesis about the BHC, called the “Mafia Hypothesis.” (Don’t you just love that?) Under this hypothesis, the host species is aware that the egg is an impostor, but takes no action against it because of the perceived threat of the BHC exacting revenge by returning to the nest and destroying the host’s own eggs. Possible evidence for this idea includes BHCs revisiting parasitized nests and occasionally destroying eggs within them following a rejection of its own egg.

And now back to our friend the House Finch. In the chart above, I’ve grouped the BHC-target species in 2 groups. Category 1 accepts the eggs, Category 2 rejects them. The House Finch is firmly in Category 1; it routinely accepts and incubates BHC eggs, and feeds BHC hatchlings. But here’s where things get interesting: over a 5-year study of 99 BHC-parasitized House Finch nests, not one BHC hatchling survived. Although a majority of BHC eggs were successfully incubated and hatched, the average life span of the hatchlings was just 3 days. All but one were dead after a week. The dead hatchlings were developmentally retarded, weighing 22% less than normal at death, and feather growth appeared to be delayed. After 14 days, the one survivor fledged (left the nest), but was found dead the next day.

And now back to our friend the House Finch. In the chart above, I’ve grouped the BHC-target species in 2 groups. Category 1 accepts the eggs, Category 2 rejects them. The House Finch is firmly in Category 1; it routinely accepts and incubates BHC eggs, and feeds BHC hatchlings. But here’s where things get interesting: over a 5-year study of 99 BHC-parasitized House Finch nests, not one BHC hatchling survived. Although a majority of BHC eggs were successfully incubated and hatched, the average life span of the hatchlings was just 3 days. All but one were dead after a week. The dead hatchlings were developmentally retarded, weighing 22% less than normal at death, and feather growth appeared to be delayed. After 14 days, the one survivor fledged (left the nest), but was found dead the next day.

So, BHCs regularly parasitize House Finch nests. House Finches are (apparently) duped. They obligingly play the part cast for them of sucker/foster parent. But (virtually) none of the BHC chicks survive. What’s going on?

What’s going is diet. This past week, the House Finches have been cleaning out my feeder daily. And that feeder is filled with seeds. House Finches are vegetarians, and feed their young regurgitated seeds and other plant matter. But BHCs are insectivores; that’s why they follow cattle around. And a chick from a species that’s evolved to thrive on the protein-rich diet of bugs fares miserably when raised on a vegetarian diet.

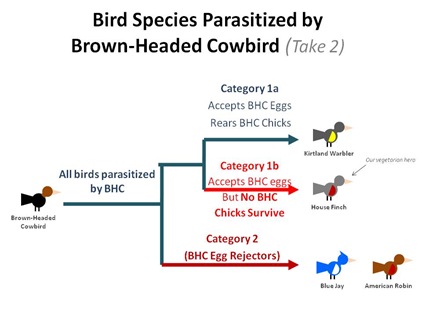

And so the real group of BHC target-hosts looks more like this:

With House Finches in a Category 1B- birds that accept the impostor egg, but from whose nests (virtually) no adult BHCs are ever raised. Last laugh is on the Cowbird.

With House Finches in a Category 1B- birds that accept the impostor egg, but from whose nests (virtually) no adult BHCs are ever raised. Last laugh is on the Cowbird.

So why would the BHC waste its time, effort and eggs parasitizing House Finch nests? The likeliest answer is that their historic ranges had minimal overlap. Both birds have seen dramatic, human-caused range expansions over the past century, which have brought them into broad contact. Perhaps after more time together, BHCs parasitism of House Finch nests will decrease. (And in fact there may already be indications that this is the case in the Eastern US.)

As its range has expanded, the BHC has come into contact with dozens of new bird species. Its versatility in targeting new species is sometimes a home run, as in the case of the Kirtland Warbler, and sometimes, as with the House Finch, a dead end.

As its range has expanded, the BHC has come into contact with dozens of new bird species. Its versatility in targeting new species is sometimes a home run, as in the case of the Kirtland Warbler, and sometimes, as with the House Finch, a dead end.

Tangent: Similar studies have been conducted with BHC eggs in the nests of American Goldfinches and European Sparrows- both seed-eaters- with similarly dismal results for the BHC.

Tangent: Similar studies have been conducted with BHC eggs in the nests of American Goldfinches and European Sparrows- both seed-eaters- with similarly dismal results for the BHC.

That wraps up Bird Feeder Week. I hope you enjoyed reading about it as much as I did blogging it. There’s been lots more going on at the feeder this past week, and some new arrivals, including a pair of Spotted Towhees, Pipilo maculates. But it’s time to take a break from birds and get back to plants.

Excellent, and most intriguing... There's always so much more going on out there than meets the eye. Keep 'em coming!

ReplyDeleteYes, I enjoyed bird week and a good choice to end with the Cow Bird - fascinating.

ReplyDeleteAppreciate the information contained here. I'm in Omaha, NE and have a pair of house finches returning for the second year to nest in a hanging plant (last year geraniums, this year pansies). When I left on a week long business trip they had five finch eggs. Upon return they have two finch eggs and what I now believe, based on a couple hours of internet research, to be a brown-headed cowbird egg. Some of the other sites noted that the cowbird evolved to be dependent on moving bison herds for insects thus couldn't afford to nest like most birds due to a loss of food when the herd moved on. I started out vested with the finches and was set to pull that cowbird egg. Based on this blog and none of these birds being threatened, I think we'll let nature run its course.

ReplyDeleteADanko- just saw your comment now (auto-copy wasn't on in the old days...) If you set a self-copy on comments (and receive this) I'd be curious to know what eventually hatched, and how the various hatchlings fared? Thx.

ReplyDeleteAs it turned out they all hatched however, the cowbird egg hatched a week after the finch eggs. The cowbird chick disappeared within two days, both finches eventually fledged and flew off.

ReplyDeleteADanko- thanks for getting back to me and sharing your observations. I appreciate it!

ReplyDelete