So I’m just dying to dive into a geeky post all about Lichens following our St. George weekend (I am telling you, the desert is like Lichen City) but today I’m going to make a brief detour to address a (very good) question from a reader.

Last week, reader Ski Bike Junkie (SBJ) commented:

We live in Suncrest at about 6300 feet. The trees in our yard are six years old, but they look scrawny and pathetic. Probably something to do with the climate here. Please don't ask me to identify them. They're currently covered with snow, not that it makes any difference.

Anyway, supposing that I like trees and would like something to grow to the point of being reasonably large but more important, healthy, what should I plant?

Long-time readers may recall that last Fall I had a revelation whereby I realized that if I acted “nice” and “helpful”* towards commenters with questions, it might actually encourage more people to comment, or frankly just read**, my blog.

*This is somewhat in contrast to my general demeanor in the real world, which can be described as “snarky” and “unhelpful”.

**Like most bloggers, I always like to act all, “Oh it’s not important whether and how many people read my blog, that’s not the point…”, but secretly I’m always like, “Christ, I spend enough time on these stupid graphics, it’d be nice if someone actually read this thing…”

So in that continuing sprit, I’m going to answer SBJ’s question, and not just point him to one of my lame Tree-ID graphics. And SBJ’s question is a great one, because Suncrest is a tricky place for a yard, as we’ll talk about in a moment. But first, for non-Utah readers, what is Suncrest?

Salt Lake Valley is bounded on the East by the Wasatch range and on the West by the Oquirrh range. On the South end the valley is separated from Utah Valley by a relatively low (by Utah standards) East-West ridge called the Traverse Mountains, which is actually geologically continuous with the Oquirrhs. The Western end of the ridge features clearly visible shorelines of ancient Lake Bonneville, and in fact much of this part of the ridge is an ancient sandbar, laid down by Lake Bonneville, and the several, similar lakes which preceded it during earlier glacial periods.

Salt Lake Valley is bounded on the East by the Wasatch range and on the West by the Oquirrh range. On the South end the valley is separated from Utah Valley by a relatively low (by Utah standards) East-West ridge called the Traverse Mountains, which is actually geologically continuous with the Oquirrhs. The Western end of the ridge features clearly visible shorelines of ancient Lake Bonneville, and in fact much of this part of the ridge is an ancient sandbar, laid down by Lake Bonneville, and the several, similar lakes which preceded it during earlier glacial periods.

When I moved here the Traverse range was “wild”, but over the last several years a development- called Suncrest- has been built with a few thousand(?) homes. Suncrest offers both advantages and disadvantages. On the plus side it’s almost always above the valley inversions in winter, and is often several degrees cooler in summer. It offers outstanding views, and access to a great trail network.

Tangent: One of the rare/ancient hybrid oaks I discovered and blogged about is located in this trail network.

On the downside, it gets a good deal more snow than the valley, making commuting pretty hairy at times, and then, the wind… I don’t know how Suncresters tolerate the wind up there.

On the downside, it gets a good deal more snow than the valley, making commuting pretty hairy at times, and then, the wind… I don’t know how Suncresters tolerate the wind up there.

The native trees up there are almost all Gambel Oak, Bigtooth Maple, and some Mountain Mahogany, both Curlleaf and Alderleaf. None grow very tall.

Tangent: Down lower on the East benches, in neighborhoods like St. Mary’s and Olympus Cove, stands of Oak have been preserved in many yards and developed into nice shade trees. But the native Oaks up on Suncrest are much shrubbier, due to the tough climate. If you ever want to see what Gambel Oak looks like under ideal growing conditions, visit Red Butte Gardens, and walk through the groves just South of the mouth of Red Butte Canyon.

OK, so that’s Suncrest. So what should SBJ grow in his yard? My first inclination was to answer his question like I do pretty much all questions here at WTWWU, or at work, or when my kids ask me something hard- just wing it. But then I thought about SBJ spending a bunch of time and effort following my advice, and then everything dying, and then years later, him saying something like, “Yeah, I used to read that plant-guy’s stupid blog, till he ruined my yard. Now my kids just play in the dirt. Someday… someday I’ll get even…”

Am I Ever Going To Just Answer His Question Already?

So I consulted with an expert. My friend Janette Diegel is the owner/proprietor of Waterwise Design & Landscapes, a Salt Lake-area landscape design, consulting and installation company. Janette specializes in water-efficient landscapes designed for our high desert environment.

More About Janette: Janette is the spouse of my biking buddy Rainbow-Spirit Paul and the sister-in-law of Avalanche-Rescue-Hero Tom Diegel, both of whom I’ve mentioned in this blog. Janette’s done work for Awesome Wife and me, and we strongly recommend her services.

Janette’s done several jobs up on Traverse Mountain, and was a wealth of information for this post.

The first, very practical, piece of advice from Janette is to check the Suncrest regulations. In the past she’s found them to be very strict, and the approval process tedious when trying to do things like use native grasses.

Janette suspects a systemic problem, since all of SBJ’s trees are affected, and shared with me these possible problems:

Climate: High wind, low water, exposed in winter, hot sun in summer.

Soil: This was news to me- Janette says the soil is awful- rocky and sparse- and in many cases in the process of building, heavy equipment was driven around and compacted the soil around the houses. Many landscapers solve this problem by laying down 4” of new topsoil, then installing a sprinkling systems for the turf, and expecting the same system to water the trees and shrubs. But up on the ridge most of this sprinkled water gets blown away and fails to saturate the root-balls of any trees. The problem is compounded by most landscapers using standard trees off their “pick lists”, which do well down in the valley, but not up on the ridge.

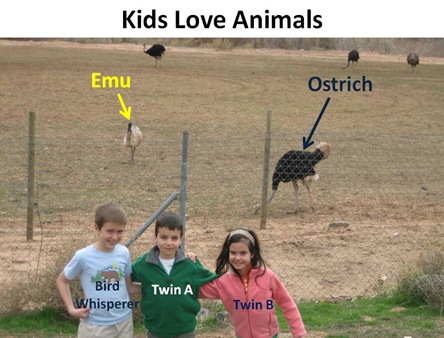

Critters: Deer, Elk, Porcupines (way cool critters, part of a group called Xenarthans, and a legacy of the Great American Interchange- I am so doing a post on them this year) are all bark-eaters, and can further damage stressed trees.

Critters: Deer, Elk, Porcupines (way cool critters, part of a group called Xenarthans, and a legacy of the Great American Interchange- I am so doing a post on them this year) are all bark-eaters, and can further damage stressed trees.

So what to plant? Native trees are great, but the Suncrest natives don’t get very big on a ridgeline. Here are some ideas, with pros and cons. For this section, the input is from Janette, with (probably not very) helpful additional comments from me in red italics. In addition I’ve provided links to Janette-recommended species that I’ve blogged about previously, in case you’d like more info. Here we go:

Evergreens. Only a few evergreens will tolerate SBJ’s environment. Their enemies are wind, lack of water in winter (assuming irrigation in summer) and antler-rubbing Mule Deer.

Colorado Blue Spruce, Picea pungens. Grow slowly, but fairly easy to get a large tree established. You need to have it staked, though, and remove the stakes once the tree is established. (I’m down on Blue Spruce in the foothills. It is so over-planted, and looks weirdly out-of-place among the Scrub Oak.)

Colorado Blue Spruce, Picea pungens. Grow slowly, but fairly easy to get a large tree established. You need to have it staked, though, and remove the stakes once the tree is established. (I’m down on Blue Spruce in the foothills. It is so over-planted, and looks weirdly out-of-place among the Scrub Oak.)

Limber Pine, Pinus flexilis. Native environment is more sheltered, so may not be ideal for Suncrest, and will probably need plenty of water. (I like Limber Pine. Good-looking, not so pointy-weird like Blue Spruce. Plus you could attract Clark’s Nutcrackers, the Coolest Corvid Ever.)

Limber Pine, Pinus flexilis. Native environment is more sheltered, so may not be ideal for Suncrest, and will probably need plenty of water. (I like Limber Pine. Good-looking, not so pointy-weird like Blue Spruce. Plus you could attract Clark’s Nutcrackers, the Coolest Corvid Ever.)

Curlleaf Mountain Mahogany, Cercocarpus ledifolius. Native, great option, grow well (but slowly). Only downside = deer browse them big-time, so you’d need cages around them till they grew out of browsing-reach. (This would’ve been my top-choice. Cool tree, looks natural, low maintenance- except for the deer thing-and foliage all year-round.)

Curlleaf Mountain Mahogany, Cercocarpus ledifolius. Native, great option, grow well (but slowly). Only downside = deer browse them big-time, so you’d need cages around them till they grew out of browsing-reach. (This would’ve been my top-choice. Cool tree, looks natural, low maintenance- except for the deer thing-and foliage all year-round.)

Juniper- Utah or Rocky Mountain, Juniperus osteosperma or monticola. Will do well, but also browsed by deer. (I like Juniper, but I don’t think it’s as attractive as some of the other options.)

Juniper- Utah or Rocky Mountain, Juniperus osteosperma or monticola. Will do well, but also browsed by deer. (I like Juniper, but I don’t think it’s as attractive as some of the other options.)

Piñon Pine, Pinus edulis or monophyla. Not a tall tree, but better adapted than just about any other pine to that area. Hard to find a big one through a nursery. (I love Piñons- do this!)

Piñon Pine, Pinus edulis or monophyla. Not a tall tree, but better adapted than just about any other pine to that area. Hard to find a big one through a nursery. (I love Piñons- do this!)

Janet also shared some deciduous options.

Gambel Oak, Quercus gambelii. If well-watered can grow more tree-like. (Unless you still have some in your yard, the whole re-planting-exactly-what-the-developer-tore-out thing sounds redundant and boring.)

Gambel Oak, Quercus gambelii. If well-watered can grow more tree-like. (Unless you still have some in your yard, the whole re-planting-exactly-what-the-developer-tore-out thing sounds redundant and boring.)

Bigtooth Maple, Acer grandidentatum. Janette warns that most sold through nurseries are grafted onto Silver Maple rootstock and so do lousy in our alkaline soils. But if you can get true native Bigtooths they could be a good option. (Big-tooth Maple = best fall foliage ever. I like this idea.)

Bigtooth Maple, Acer grandidentatum. Janette warns that most sold through nurseries are grafted onto Silver Maple rootstock and so do lousy in our alkaline soils. But if you can get true native Bigtooths they could be a good option. (Big-tooth Maple = best fall foliage ever. I like this idea.)

Netleaf Hackberry, Celtis reticulata. Same size & shape as Mountain Mahogany, but has to be “trained” into tree form. (Sounds like a mega-hassle.)

Netleaf Hackberry, Celtis reticulata. Same size & shape as Mountain Mahogany, but has to be “trained” into tree form. (Sounds like a mega-hassle.)

Alderleaf Mountain Mahogany, Cercocarpus montanus. Deciduous version of Curlleaf (above.) Solves the deer problem, but bare in the winter. (This could be the best, lowest-hassle choice overall.)

Alderleaf Mountain Mahogany, Cercocarpus montanus. Deciduous version of Curlleaf (above.) Solves the deer problem, but bare in the winter. (This could be the best, lowest-hassle choice overall.)

Singleleaf Ash, Fraxinus anomala. Janette hasn’t tried this tree, but says others have and like it.

Singleleaf Ash, Fraxinus anomala. Janette hasn’t tried this tree, but says others have and like it.

On top of all these, Janette says there are a bunch of non-native trees that would work, but all would require some degree of care/hassle…

So SBJ, you’ve got plenty of options. My personal vote is a Mountain Mahogany-Pinon-Bigtooth Maple combo, but then I’m not the one maintaining (or paying) for it. My 2 cents: Get some professional advice before you start tearing stuff out. Get a pro like Janette to come over and have a gander at your yard.

A big thank-you to Janette for helping me with this post- you’re the best!

Of course, SBJ, another, extreme low-maintenance, option would be just to fill your yard with big rocks and watch the lichens grow on them…

Next Up: All About Lichen!

Colorado Blue Spruce

Colorado Blue Spruce Limber Pine

Limber Pine Curlleaf Mountain Mahogany

Curlleaf Mountain Mahogany Juniper

Juniper Piñon Pine

Piñon Pine Gambel Oak

Gambel Oak Bigtooth Maple

Bigtooth Maple