Yes, I know I said I was going to post about lichens today, but I changed my mind. I’m doing Moss first. Here’s why:

1- Lichens are so cool that I want to finish off this series with them.

2- Blogging about Moss will allow me to correct one of the biggest errors I’ve made in this blog.

Side Note: Last summer I established a precedent whereby I acknowledge, and- where feasible and practical- correct, errors in this blog. Though I suspect these corrections are a bit tedious for readers, hey, it’s my blog.

3- Lichens are more complicated, meaning that the Lichen post will take more work. And since today is my birthday*, I don’t really feel like working that hard on a post.

* Yeah, that’s right. Me, Liz Taylor, Ralph Nader and Chelsea Clinton all turn a year older today. Tonight the 4 of us are getting together and having a hootenanny. (Jodie: “Hootenanny” is your new word for the day.)

But first, some general thoughts about things that grow on rocks. Back a couple of years ago when I started getting interested in trees, and learning to identify them, it was like having a veil lifted from my eyes; all of a sudden I started seeing trees for the first time, and suddenly trees I recognized were everywhere.

But first, some general thoughts about things that grow on rocks. Back a couple of years ago when I started getting interested in trees, and learning to identify them, it was like having a veil lifted from my eyes; all of a sudden I started seeing trees for the first time, and suddenly trees I recognized were everywhere.

This winter, something similar has been happening with moss and lichens. My whole life I never bothered giving these things a second glance, and since I started noticing them, suddenly they’re everywhere- I can’t walk 20 feet in the desert, foothills or forest without seeing Moss and Lichen!

Last weekend around St. George, the Mosses were lusher and lovelier than I’d ever seen. Check out this wall along Zen Trail. In the middle of that harsh, rocky, gnarly, shrubby desert is this beautiful, lush green wall.

Last weekend around St. George, the Mosses were lusher and lovelier than I’d ever seen. Check out this wall along Zen Trail. In the middle of that harsh, rocky, gnarly, shrubby desert is this beautiful, lush green wall.

Here’s another such wall, and this one is in Sonora, Mexico, just below the peak of Cerro El Volcan, high point of the Sierra Durazno range. Arizona Steve climbed it in January 2007 (probably the first gringos to do so in years, if not decades), and were amazed to find this lush wall just short of the summit.

Here’s another such wall, and this one is in Sonora, Mexico, just below the peak of Cerro El Volcan, high point of the Sierra Durazno range. Arizona Steve climbed it in January 2007 (probably the first gringos to do so in years, if not decades), and were amazed to find this lush wall just short of the summit.

And of course, closer to home is my favorite “Mossy Wall”, which I blogged about in my previous Moss post, back in November. I have mixed feelings about that post. I liked that I covered some of the absolutely coolest things about Moss, but was disappointed that I botched the ID so badly. To review, 3 of the really cool things I highlighted in that post were:

And of course, closer to home is my favorite “Mossy Wall”, which I blogged about in my previous Moss post, back in November. I have mixed feelings about that post. I liked that I covered some of the absolutely coolest things about Moss, but was disappointed that I botched the ID so badly. To review, 3 of the really cool things I highlighted in that post were:

1-Haploid Dominance. Mosses use a weird, alternating-generation reproductive strategy that is completely unlike anything in trees (with the technical exception of fern trees), flowers or animals (including bugs.) I won’t repeat it here, but it’s worth re-reading if you don’t know it. Additionally, a cool thing I’ve learned since about haploid dominance is this: some biologists suspect that it might actually accelerate evolution and speciation, the reason being that natural selection might exert greater pressure on an organism that has no “back-up” or alternative gene at any given locus.

1-Haploid Dominance. Mosses use a weird, alternating-generation reproductive strategy that is completely unlike anything in trees (with the technical exception of fern trees), flowers or animals (including bugs.) I won’t repeat it here, but it’s worth re-reading if you don’t know it. Additionally, a cool thing I’ve learned since about haploid dominance is this: some biologists suspect that it might actually accelerate evolution and speciation, the reason being that natural selection might exert greater pressure on an organism that has no “back-up” or alternative gene at any given locus.  In other words, in a haploid dominant organism, every chromosome is like the X or Y chromosome in a human male- there’s no back-up copy. And all the things I’ve mentioned that human males suffer from as a result, including color-blindness and hemophilia, are analogous to problems a Moss could suffer on any chromosome.

In other words, in a haploid dominant organism, every chromosome is like the X or Y chromosome in a human male- there’s no back-up copy. And all the things I’ve mentioned that human males suffer from as a result, including color-blindness and hemophilia, are analogous to problems a Moss could suffer on any chromosome.

2- Mosses have no real vascular system- no xylem, phloem or roots. They’re bare-bones plants. They preceded vascular plants and colonized the land well before them. Without a complex vascular system to support, Mosses can efficiently photosynthesize at temps just a bit above freezing, unlike trees for instance, which generally can’t do so efficiently below about 50F. This is why mosses stay green all winter.

3- Another benefit o their bare-bones physiology is that mosses can survive long periods of dormant “desiccation”, dried up and brown, then springing back to life when moisture is available, and this is why so many mosses do well in the desert.

And so when we visited St. George last weekend, the temps were climbing, there’d been plenty of recent rains, but while the (vascular) Blackbrush was just starting to sprout leaves, the (minimalist) mosses were already photosynthesizing at full throttle, which made them so spectacularly, vibrantly green and lovely.

And so when we visited St. George last weekend, the temps were climbing, there’d been plenty of recent rains, but while the (vascular) Blackbrush was just starting to sprout leaves, the (minimalist) mosses were already photosynthesizing at full throttle, which made them so spectacularly, vibrantly green and lovely.

So the big mistake of that post was identifying the Mossy Wall moss as Sphagnum. It’s not. Since November, with the help of several friends, I tracked down one of the world’s finest bryologists, Lloyd Stark of UNLV, and his graduate student, John Brinda, and together Lloyd and John have helped me to identify the Mossy Wall moss, as well as the other mosses highlighted in this post.

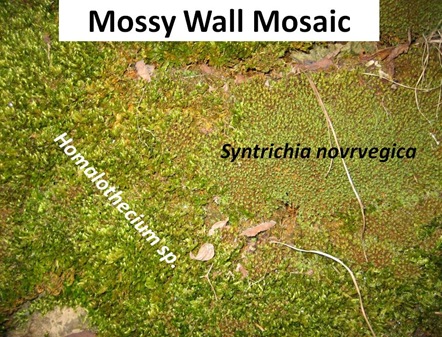

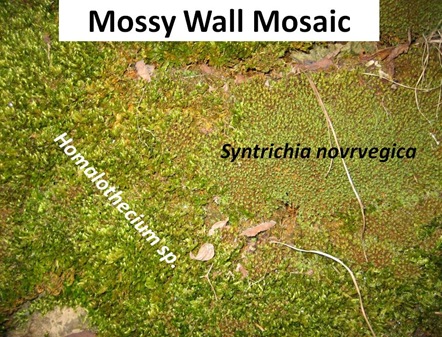

The Mossy Wall moss is actually 2 different species. Since then I’ve seen these same 2 all over the Wasatch, so it’s worth remembering them. In the photo below you can clearly see the patchwork between the 2 different species.

The brushier, “fuller “-looking moss has what I’ve been calling “Bottle-brush” heads, which are visible in the photo below. This is a species of the genus Homalothecium, which is one of 135 genera in the order Hypnales. The Hypnales are known as “Feather Mosses”, which come to think of it, is a much better name than “Bottle-brush.”

The brushier, “fuller “-looking moss has what I’ve been calling “Bottle-brush” heads, which are visible in the photo below. This is a species of the genus Homalothecium, which is one of 135 genera in the order Hypnales. The Hypnales are known as “Feather Mosses”, which come to think of it, is a much better name than “Bottle-brush.”

The “lower” looking moss has what I’ve been calling “spiky/leafy” heads, and is probably Syntrichia norvegica. What I like about this photo is that you can clearly see sporophytes (the diploid generation) in the upper right.

The “lower” looking moss has what I’ve been calling “spiky/leafy” heads, and is probably Syntrichia norvegica. What I like about this photo is that you can clearly see sporophytes (the diploid generation) in the upper right.

Tangent: So although I suck as a wildlife photographer, can we just agree that these are some totally rocking moss photos??

Tangent: So although I suck as a wildlife photographer, can we just agree that these are some totally rocking moss photos??

The genus Syntrichia belongs to a completely different order- Pottiales- and so the Mossy Wall, which I thought was just one species of “moss” is actually a mosaic of 2, very different and distantly-related species.

Back to the Desert

OK, so now that I’ve been set straight on the mosses on my favorite rock wall, let’s get back to St. George. This moss, below, is all over the place down there (this photo is from the Church Rocks trail, right by the culvert that goes under I-15.). It belongs to the genus Grimmia, and is most likely Grimmia laevigata, commonly known as either Cushion Moss or Dry Rock Moss.

G. laevigata is one of the toughest, most widespread, successful plants on the planet. It occurs on every continent except Antarctica, and in many areas in the Southwest- particular granitic boulders- it is the dominant plant. Despite its worldwide distribution, it shows little genetic variability across the continents, a characteristic that has made it the subject of much interest to, and study by, bryologists.

G. laevigata is one of the toughest, most widespread, successful plants on the planet. It occurs on every continent except Antarctica, and in many areas in the Southwest- particular granitic boulders- it is the dominant plant. Despite its worldwide distribution, it shows little genetic variability across the continents, a characteristic that has made it the subject of much interest to, and study by, bryologists.

G. laevigata is a “pioneer” moss, in that it is often the first thing to colonize exposed granite surfaces, frequently even before lichens. But the absolute coolest thing about G. laegivata is its desiccation tolerance; it can be completely dried out for 10 years or more, then spring back to life, green and soft, when the rains return. In fact what ultimately limits G. laegivata from growing in even drier, sunnier, hotter places isn’t the lack of moisture, so much as its ability to maintain an viable carbon balance under extreme cycles of rapid desiccation (caused by direct sunlight) and rehydration, which is why, in the desert, you generally find this moss on North-facing rocks.

G. laevigata is a “pioneer” moss, in that it is often the first thing to colonize exposed granite surfaces, frequently even before lichens. But the absolute coolest thing about G. laegivata is its desiccation tolerance; it can be completely dried out for 10 years or more, then spring back to life, green and soft, when the rains return. In fact what ultimately limits G. laegivata from growing in even drier, sunnier, hotter places isn’t the lack of moisture, so much as its ability to maintain an viable carbon balance under extreme cycles of rapid desiccation (caused by direct sunlight) and rehydration, which is why, in the desert, you generally find this moss on North-facing rocks.

Common as G. laegivata is, there are plenty of other mosses around St. George. Below is another Grimmia species, G. pulvinata. This is another great photo, with lots of distinctive, down-turned sporophytes visible.

Back on Zen trail, occurring alongside G. pulvinata, is another spiky/leafy-headed moss, and it turns out that this is another Syntrichia species, probably either S. papillopsissima or S. ruralis, and a close cousin of our Mossy Wall S. norvegica back home. I love this one; I think it’s the prettiest close-up moss- and maybe one of the best-looking plants overall- I’ve ever seen.

Back on Zen trail, occurring alongside G. pulvinata, is another spiky/leafy-headed moss, and it turns out that this is another Syntrichia species, probably either S. papillopsissima or S. ruralis, and a close cousin of our Mossy Wall S. norvegica back home. I love this one; I think it’s the prettiest close-up moss- and maybe one of the best-looking plants overall- I’ve ever seen.

The thing that fascinates me about these mosses is this: I’ve mentioned before that one of the things I like about trees is being able to look around and know where you are- region, altitude, etc.

The thing that fascinates me about these mosses is this: I’ve mentioned before that one of the things I like about trees is being able to look around and know where you are- region, altitude, etc.  A bryologist can do the same thing with mosses, but with a perspective that is an order of magnitude greater than a tree-lover because there are so many more species of moss around- almost like the difference between looking at the world in human (trichromatic) color vision and Pigeon (pentachromatic) color vision. In any given canyon in the Wasatch there are probably more species of moss than there are trees in the entire state of Utah, and while most of us amateurs can’t hope to recognize more than a handful of species, just some basic understanding of mosses can give you at least a glimpse of the amazing “smaller-level” botanical richness and variety all around.

A bryologist can do the same thing with mosses, but with a perspective that is an order of magnitude greater than a tree-lover because there are so many more species of moss around- almost like the difference between looking at the world in human (trichromatic) color vision and Pigeon (pentachromatic) color vision. In any given canyon in the Wasatch there are probably more species of moss than there are trees in the entire state of Utah, and while most of us amateurs can’t hope to recognize more than a handful of species, just some basic understanding of mosses can give you at least a glimpse of the amazing “smaller-level” botanical richness and variety all around.

But cool as Mosses are, Lichens are even cooler and weirder. Because though they seem to spread and grow like plants, they’re not quite plants, but rather an amazing symbiosis of the most basic of all plants and that weird, so-hard-to-get-your-head-around, third great kingdom of multi-cellular life: Fungi.

But cool as Mosses are, Lichens are even cooler and weirder. Because though they seem to spread and grow like plants, they’re not quite plants, but rather an amazing symbiosis of the most basic of all plants and that weird, so-hard-to-get-your-head-around, third great kingdom of multi-cellular life: Fungi.

Special Thank You: I am exceedingly grateful to Lloyd Stark and John Brinda, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, for their time and efforts in identifying the species highlighted in this post, as well to Larry St. Clair of Brigham Young University for (repeatedly) forwarding my inquiries and photos to Lloyd and John. The assistance and courtesy extended to me repeatedly by botanical researchers and specialists has been, and continues to be, one of the most rewarding aspects of this entire project.

(Larry, by the way, is a lichenologist, and the star of my next post.)

9 comments:

I love this blog. I am too ignorant to comment on it, but I thoroughly enjoy reading it. Thanks!

-->relurk<--

Congrats on another circle 'round the sun, it should be quite the hootenanny with the gang.

I found your blog through Fat Cyclist and enjoy catching up on the biology I never had during my formative years though I can't imagine how you find the time for such thorough treatise on the various topics.

Keep up the good work!

Another good post.

I remember as a kid I would occasionally study moss and lichen - get down close and look at the structures, shapes, growth patterns, colors, etc. They always seemed to catch my eye. And moss feels so cool - I'd run my hand over it - I think I even laid my cheek on it a few times because it looked like it might make a good pillow.

It seems you tapped back into that state of wonder. I think I need to do the same.

And happy birthday! And if you receive that item I think you might be receiving, I look forward to your impressions. (I hope I didn't give you a bum recommendation.)

Very interesting post Watcher. I've always thought of moss as a group (order, phyla, or whatever) of plants that thrives in wet climates (we are up to our berries in mosses up here in the PNW). Interesting to think of them as doing well in the desert. I'll be on the lookout for mosses next time I head to the dry side.

Chris in Portland

Jodie- I see I will have to work harder. I will try next week to work "dick-dance" into a post.

KathyR, WheelDancer- thanks for the kind words, I really appreciate it.

Chris- That's what I thought, too, which is why the whole moss thing has been such an eye-opener for me. I'm going to try to do a better job this year paying attention to the "little stuff".

KKris- Awesome Wife delivered- I got 'em! I'll post about them next week, but all I can say now is Holy Crap. Unbelievable clarity.

Great post. I really enjoyed reading about the mosses and the photos are super.

Questions!

1) If mosses don't have roots, then how do they absorb nutrients? From water? And if so, from water only, or do they have some way of getting nutrition from whatever substrate they're sitting on?

2) I have the impression that mosses are designed to hold water like a sponge -- maybe not individual plants, but the fractal mass of the moss colony as a whole. True?

Doug M. (not Claudia)

Doug M. (Not Claudia)- Answers!

Mosses absorb water and nutrients from the atmosphere.In addition mosses are anchored to a surface by small rooty-looking growths called rhizoids. Rhizoids lack specialized conducting cells, but have a "fuzzy" structure which, according to several sources I found, allows some additional absorption of water and nutrients, depending on the moss and the surface it's growing on.

Mosses definitely hold water in a sponge-like way. In fact, this is a big reason for adding peat moss (Sphagnum) to gardening soil; water is held longer and released gradually.

Very interesting. One of my favorite riding spots is within granite outcroppings with tons of "moss" and "lichens" it is good to know more about them.

Post a Comment