Note: I tried real hard to squeeze all the Costa Rican plant stuff into 1 post. Really. Couldn’t do it, and you’ll see why after this post and the next.

*Well I guess I could, but then it would be another Monster Post (like the Lichen post), and Jodie and Kelly would make fun of me and roll their eyes again the next time they talked to me about my blog…

So far I’ve covered the easy stuff- mammals, birds. Now for the hard stuff- plants.

Last week I saw more species of trees- just trees- in 1 week than I’ve seen throughout the US in an entire year of doing this blog. Costa Rica has a land area less than ¼ that of Utah. Utah has maybe 30 different tree species total. Costa Rica has 30 times that. And that’s just trees. Costa Rica has some 9,000 species of vascular plants, including 1400 species of orchids alone! Any plant/tree type you look at, the diversity and complexity down there is simply dazzling.

Last week I saw more species of trees- just trees- in 1 week than I’ve seen throughout the US in an entire year of doing this blog. Costa Rica has a land area less than ¼ that of Utah. Utah has maybe 30 different tree species total. Costa Rica has 30 times that. And that’s just trees. Costa Rica has some 9,000 species of vascular plants, including 1400 species of orchids alone! Any plant/tree type you look at, the diversity and complexity down there is simply dazzling.

Here’s a quick example: Palms, which I blogged about last Spring. In the whole Western US, there’s one native Palm species, Washingtonia filifera. Sure there are bunch of exotics in gardens, office parks and along boulevards, but none of them- to my knowledge- have naturalized to any extent in the Western US.

Costa Rica has 109 species of Palms, both native and naturalized exotics. And even the exotics have fascinating stories. The Coconut Palm, Cocos nucifera, (pic left lining deserted beach) grows all over the place, but occurs in 2 distinct varieties, one on the Caribbean side, and the other on the Pacific.

Costa Rica has 109 species of Palms, both native and naturalized exotics. And even the exotics have fascinating stories. The Coconut Palm, Cocos nucifera, (pic left lining deserted beach) grows all over the place, but occurs in 2 distinct varieties, one on the Caribbean side, and the other on the Pacific.  Coconut Palms evolved somewhere around Pacific or Indian Ocean islands, and have migrated or been introduced throughout the tropics. The Caribbean variety was introduced by settlers bringing Coconut Palms from Africa. But the Pacific variety came the other direction, and was either introduced or migrated on its own (via floating coconuts)- it’s not clear which- across the Pacific. In other words in Costa Rica the Magellan-like circumnavigation of the world by the Coconut Palm has come full circle.

Coconut Palms evolved somewhere around Pacific or Indian Ocean islands, and have migrated or been introduced throughout the tropics. The Caribbean variety was introduced by settlers bringing Coconut Palms from Africa. But the Pacific variety came the other direction, and was either introduced or migrated on its own (via floating coconuts)- it’s not clear which- across the Pacific. In other words in Costa Rica the Magellan-like circumnavigation of the world by the Coconut Palm has come full circle.

The native palms are of course beautiful and interesting as well. The most common “pasture” Palm throughout the country is the Coyol Palm, Acrocomia aculeata, (pic above, right) and my personal favorite native was this guy, the Rooster-tail Palm, Calyptrogyne sp., (pic left) which was pretty common down by Manuel Antonio.

The native palms are of course beautiful and interesting as well. The most common “pasture” Palm throughout the country is the Coyol Palm, Acrocomia aculeata, (pic above, right) and my personal favorite native was this guy, the Rooster-tail Palm, Calyptrogyne sp., (pic left) which was pretty common down by Manuel Antonio.

Side Note: There are 17 species of Calyptrogyne. I think this one might be C. ghiesbreghtiana, which is actually pollinated by bats. And speaking of Palm pollination, to reach our hotel, we had to drive through a couple of kilometers of Palm plantations. The Palms in question were African Oil Palms, Elaeis guineensis, which are pollinated by, of all things, a Weevil*.

*Notice how we keep coming back to Weevils over and over and over again? I am telling you, Weevils rule the world, and we are just along for the ride. Somewhere, deep in some dark tropical jungle, I’ll bet there’s like this elite governing council of Weevil-Illuminati who secretly plot the course of entire planet, including- among other things- how long they should keep us around…

What’s interesting about the Latitude vs. Diversity trend is that it continues the further North or South from the equator you go. The Canadian Boreal forest is dominated by just 9 tree species. And the declining diversity isn’t just in plants- it’s the same deal with birds, mammals, insects and fungi.

So you’d think that like most big obvious trends in the natural world- like why exotic species wreak havoc on islands or why overgrazing damages grasslands, or why vultures defecate on their legs (to keep cool)- there’d be some simple, clear, logical textbook explanation of why species diversity is so much greater in the tropics. But amazingly, there’s not. There are dozens of theories/hypotheses, and significant problems with pretty much all of them. Some of the more popular include:

So you’d think that like most big obvious trends in the natural world- like why exotic species wreak havoc on islands or why overgrazing damages grasslands, or why vultures defecate on their legs (to keep cool)- there’d be some simple, clear, logical textbook explanation of why species diversity is so much greater in the tropics. But amazingly, there’s not. There are dozens of theories/hypotheses, and significant problems with pretty much all of them. Some of the more popular include:

1-More energy from the sun = faster growth, development and speciation

2-Tropical creatures live under benign-to-optimal environmental/climatic conditions. They fine-tune/optimize for these environments and therefore minor differences in environment- valleys, different drainages, rain-shadows have amplified effects on tropical organisms, which drives speciation.

2-Tropical creatures live under benign-to-optimal environmental/climatic conditions. They fine-tune/optimize for these environments and therefore minor differences in environment- valleys, different drainages, rain-shadows have amplified effects on tropical organisms, which drives speciation.

3-Speciation is in part a reaction to parasites, and colder climates limit the growth/survival of parasites.

4-Repeated climate swings/ice ages in higher-latitude climes drive more frequent extinctions, leaving a smaller number of species following each such swing.

4-Repeated climate swings/ice ages in higher-latitude climes drive more frequent extinctions, leaving a smaller number of species following each such swing.

5-In warmer climes, biggest pressures on living things are from other living things, which drives speciation. In colder climes, biggest pressure = environmental conditions.

I’m not qualified to weigh in, but I’m partial to #3, because a) I “get it” better than I do some of the other explanations, and b) parasite-pressure is one of the leading the suspects as to why sexual reproduction is so much more common than asexual reproduction among plants and animals.

Whatever its cause, the diversity of the tropics can be a bit intimidating for the wannabe amateur botanist, but with a patience and a good plant guide, by the end of a week you can start to get your bearings in the rain/cloud forest. The book I picked up was outstanding: Tropical Plants of Costa Rica, by Willow Zuchowski*, an American ex-pat botanist who’s lived in the Monteverde area for 20 years. It’s not only the best plant guide I found for Costa Rica; it’s the best plant guide I’ve bought, ever.

Whatever its cause, the diversity of the tropics can be a bit intimidating for the wannabe amateur botanist, but with a patience and a good plant guide, by the end of a week you can start to get your bearings in the rain/cloud forest. The book I picked up was outstanding: Tropical Plants of Costa Rica, by Willow Zuchowski*, an American ex-pat botanist who’s lived in the Monteverde area for 20 years. It’s not only the best plant guide I found for Costa Rica; it’s the best plant guide I’ve bought, ever.

*Remember her, we’ll come back to her tomorrow.

Tangent: Going from amateur botany in Utah to amateur botany in CR is a lot like upgrading categories in bike racing. You race for a while in a category, get used to finishing in the top 3 or 5 pretty much every race, and you start to think, “Hey, I’m a pretty good racer…” Then you upgrade to the next category, and it’s like, “Holy crap! Everyone here is like me! This is really hard!”

Tangent: Going from amateur botany in Utah to amateur botany in CR is a lot like upgrading categories in bike racing. You race for a while in a category, get used to finishing in the top 3 or 5 pretty much every race, and you start to think, “Hey, I’m a pretty good racer…” Then you upgrade to the next category, and it’s like, “Holy crap! Everyone here is like me! This is really hard!”

Here’s a tree-type you’ll see all over CR that’s a cinch to recognize: Cecropia, known locally as Guarumo. Their leaves are easily recognizable, like big hands with lots of fingers. They’re most common in open, or previously cleared areas, often along roadsides or the edge of forests, but they also do great up in the cloud forests, quickly exploiting any new gaps in the canopy. They’re shade intolerant, love direct sunlight, and can grow an astounding 4 meters per year.

Here’s a tree-type you’ll see all over CR that’s a cinch to recognize: Cecropia, known locally as Guarumo. Their leaves are easily recognizable, like big hands with lots of fingers. They’re most common in open, or previously cleared areas, often along roadsides or the edge of forests, but they also do great up in the cloud forests, quickly exploiting any new gaps in the canopy. They’re shade intolerant, love direct sunlight, and can grow an astounding 4 meters per year.

For a long time it was believed that sloths preferred Cecropias to other trees as they’re most often sighted in them, but more recently it’s become apparent that they’re just spotted more often in Cecropias because those are the trees that dominate so many forest-edges. There are 4 species of Cecropia on mainland CR, and Zuchowski’s guide provides an easy identification key for them.

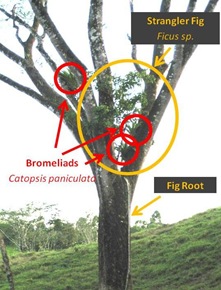

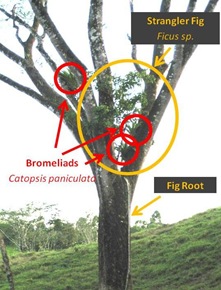

Even more interesting than the trees in CR are the epiphytes. Epiphytes are organisms which grow on other plants, and they include plants, mosses, lycophytes, ferns, fungi and lichens and even cyanobacteria. As soon as you start looking at trees in CR you start noticing them.  One of the most common is this guy, Catopsis paniculata (pic left). You first notice it by looking at a tree and thinking, hey why does that tree have 2 different types of leaves? Then you realize that the clumps of spiky leaves are separate plants, in this case C. paniculata. Catopsis is type of plant called a Bromeliad, which is a family of 2,000+ species of monocots native to the tropics of South and Central America. If you think you’re not familiar with them, you’re wrong- Pineapple, Ananas comosus, is a great example. (BTW, Pineapple is a CAM plant.) Another example you might be familiar with, and which is also common throughout CR, is Spanish Moss, Tillandsia usneoides, which is not actually a “moss” at all, but a monocot angiosperm.

One of the most common is this guy, Catopsis paniculata (pic left). You first notice it by looking at a tree and thinking, hey why does that tree have 2 different types of leaves? Then you realize that the clumps of spiky leaves are separate plants, in this case C. paniculata. Catopsis is type of plant called a Bromeliad, which is a family of 2,000+ species of monocots native to the tropics of South and Central America. If you think you’re not familiar with them, you’re wrong- Pineapple, Ananas comosus, is a great example. (BTW, Pineapple is a CAM plant.) Another example you might be familiar with, and which is also common throughout CR, is Spanish Moss, Tillandsia usneoides, which is not actually a “moss” at all, but a monocot angiosperm.

Many/most epiphytes have commensal or even mutualistic relationships with their host trees, but others are outright parasitic, the best example being Figs, or “Strangler Figs” (genus = Ficus.) Figs begin life as epiphytes on existing trees, but then drop successive roots to the ground, and grow all over and around the host tree, eventually killing it. By the time the Fig kills its host, the Fig has developed into a complete tree of its own, surrounding and enveloping the now-dead trunk of its host. The host-trunk eventually rots away, leaving a hollow, free-standing Fig tree.

Many/most epiphytes have commensal or even mutualistic relationships with their host trees, but others are outright parasitic, the best example being Figs, or “Strangler Figs” (genus = Ficus.) Figs begin life as epiphytes on existing trees, but then drop successive roots to the ground, and grow all over and around the host tree, eventually killing it. By the time the Fig kills its host, the Fig has developed into a complete tree of its own, surrounding and enveloping the now-dead trunk of its host. The host-trunk eventually rots away, leaving a hollow, free-standing Fig tree.

Figs are particularly interesting because like Palms, Joshua Trees and Bamboo, they’ve evolved a fundamentally different way of being a tree, but they’re also a bit ghoulish, like something out of Invasion of the Body Snatchers, that takes over, replaces and eventually emulates its host.

Figs are particularly interesting because like Palms, Joshua Trees and Bamboo, they’ve evolved a fundamentally different way of being a tree, but they’re also a bit ghoulish, like something out of Invasion of the Body Snatchers, that takes over, replaces and eventually emulates its host.

But the absolutely most fascinating thing about Figs is how they reproduce. A single “fig” isn’t really a fruit, but rather a flower, or technically an inflorescence. The real flowers are inside the “fruit” and this is where things get weird. Figs are fertilized by specialized wasps, the females of which bore inside the fig and lay eggs, after which they die, their bodies consumed/absorbed by the fig.

When the eggs hatch, some male, some female, the newborn wasps seek each other out and mate.

When the eggs hatch, some male, some female, the newborn wasps seek each other out and mate.

Following mating, the male chews a hole through the fruit, and then promptly dies. The pregnant female exits via the male-chewed hole, flies to another fig, chews her way inside and repeats the cycle, carrying pollen on her body from the interior-flowers of the first fig, and thereby pollinating the second…

Following mating, the male chews a hole through the fruit, and then promptly dies. The pregnant female exits via the male-chewed hole, flies to another fig, chews her way inside and repeats the cycle, carrying pollen on her body from the interior-flowers of the first fig, and thereby pollinating the second…

Tangent: And this is only the “basic” story. In the “director’s cut” version there are all sorts of additional cool twists, including other wasps that parasitize the fig wasps!

Tangent: And this is only the “basic” story. In the “director’s cut” version there are all sorts of additional cool twists, including other wasps that parasitize the fig wasps!

The interesting corollary of this cycle is that the male Fig Wasp spends his entire life inside the fig. I should mention that Fig Wasps are tiny, like 1/8 – ¼” long. We didn’t see any, but we did see a much, much bigger wasp- a Costa Rican Tarantula Hawk (genus = Pepsis.) I didn’t get a pic, but it looks a lot like the ones we get in Southern Utah- black body, orange wings- except WAY bigger, with a body as long as my forefinger.

Tangent: I once mused about the “universe-perspective” of the Sea-Monkey-Like-Brine-Shrimp inhabiting the ephemeral tiñajas on desert slickrock. If anything, the universe-perspective of a male Fig Wasp would be even more weird to contemplate.

The sting of the Tarantula Hawk, BTW, is one of the most painful stings of any insect, ranked near top of the Schmidt Pain Index, which is a comparative ranking of pain caused by various Hymenopteran (bees, ants, wasps) stings.  The pain of its sting is exceeded only by that of the Bullet Ant, Paraponera clavata, (pic left) which Bird Whisperer spotted on the trail and our guide identified for us, saying, “Touch it and we’re going to the hospital.” The Schmidt Index describes the pain from its sting as: “Pure, intense, brilliant pain. Like fire-walking over flaming charcoal with a 3-inch rusty nail in your heel”. So like the guide said, don’t touch it. Woops. I’m veering into creepie-crawlie stuff. Back to plants…

The pain of its sting is exceeded only by that of the Bullet Ant, Paraponera clavata, (pic left) which Bird Whisperer spotted on the trail and our guide identified for us, saying, “Touch it and we’re going to the hospital.” The Schmidt Index describes the pain from its sting as: “Pure, intense, brilliant pain. Like fire-walking over flaming charcoal with a 3-inch rusty nail in your heel”. So like the guide said, don’t touch it. Woops. I’m veering into creepie-crawlie stuff. Back to plants…

BTW, the figs you eat come from an Old World Fig Tree, Ficus carica.

Next Up: Tree Ferns, Heliconias, Podocarps and all about Cloud Forests

Loving all this!! Thanks for the tour, Watcher. Looking forward to tree ferns tomorrow. (Birds were spectacular too!) Your biggest problem will be deciding which post to submit to BGR (better hurry!)...

ReplyDeleteThanks for the nudge/reminder, Sally- I just shot Mary a submission.

ReplyDeleteBTW, you would be in HEAVEN in Costa Rica- it is Plant-Lover's Paradise!

Good stuff! Interesting plants.

ReplyDeleteThanks for including the description of the pain induced by the bullet ant sting - plenty vivid.

Bullet ants were mentioned on some TV program I watched. They said the name comes from the comparison of the sting to being shot.

The program also showed a tribe in Brazil that uses the ants as an initiation for warriors. The ants are immobilized with chloroform and placed into a glove with their stingers facing in. The initiate puts their hand and arm in the glove and leaves it there for 10 minutes. Numbness of the arm, dizziness, and other symptoms follow.

More info on Wikipedia - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paraponera

Just noticed the tree fern on top too, n.i.c.e!!

ReplyDeleteKK, that sounds horrible! Yikes, and thanks for sharing! :{

Great post! This isn't the best place to post this link, but you'll find it interesting.

ReplyDeletehttp://beetlesinthebush.wordpress.com/2009/03/28/trees-of-lake-tahoe-the-pines/

Beetles in the bush is a kindred spirit.

BTW, was there still an orchid "arboretum" in Santa Elena? It was very low key but well worth the visit -- they had micro orchids that are pollinated by fungus gnats that attempt to copulate with the tiny flowers. It was there about 5 yrs ago.

Tomo- I'm sad to say we missed the orchid garden. As a family trip, we had multiple constituencies to satisfy, and the reptile zoo (a winner for young children, though I ended up enjoying it too) won out on the afternoon we extra time open.

ReplyDeleteThanks for the link. Ted has a great blog, and it's an excellent post. I don't know if you were reading my blog last summer, but we've vacationed by Lake Tahoe the last 2 summers, and I'm a huge fan of Tahoe trees, so I really appreciate the link!

What a treat to find this page and to learn that there's another Southwesterner who's been gobsmacked by the Neotropics. When I was in Costa Rica a couple years ago, I wanted to weep--first from delight and then from exhaustion! Everywhere I looked, there was something I'd never seen before.

ReplyDelete~Shelley

Shelley- that's a great way to describe the experience. I love living in the Southwest, but a blast of neotropical sensory overload every once in a while really wakes me up!

ReplyDeleteGreat post - this entomologist is quickly becoming enamored with botany.

ReplyDeleteI got stung in the arm by a bullet ant in Ecuador 20 years ago. It was not only the most painful sting I had ever experienced, I was sick with flu-like symptoms for several days afterward. I continued collecting insects!

I adore the Neotropics!

I should thank Tomodactylus (whoever he/she is) for linking my blog - thanks!

regards--ted

Ted- Wow! I can't even imagine the sting. What's a bit scary is that when my 9-yr old pointed it out to me it didn't look like anything special at all. I'm so glad he didn't go poking at it.

ReplyDelete