Note: I’m away and offline this week. I’ve set up an auto-post series of this Mexican-Tree-Adventure story in my absence.

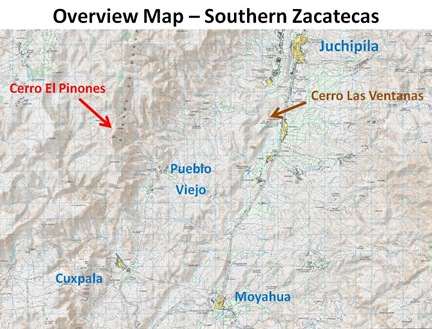

Our discussion turned to access. Miguel had no problem had at all with a stranger visiting his property, but was concerned about how I would reach it. The road to Pueblo Viejo, while passable for a passenger car, was rough, and he assured me that hiking up Cerro Piñones from the village would be long, difficult, and navigationally problematic. He indicated that another landowner, the Pintero family, had constructed a rough four-wheel-drive road to the top of the mesa, and as he was planning to drive up there on Saturday, he’d be glad to take me along.

We were in the home of Moro Pintero. The Pinteros are a family of four brothers and three sisters who own the largest single piece of Cerro Piñones. Led by the eldest brother, Isaac, they had built the road to the top, were active in maxipiñon conservation efforts, having long since banned all grazing on their property, and were in the process of building a group of “cabanas” atop the mesa, which they envisioned renting out to future visitors coming to see the rare pines. The woman was Moro’s wife, the blonde toddler his youngest daughter, and the shirtless man with the armpit bandage was his younger brother Beto, who was staying with them. Moro himself had been at the worksite atop the mesa all day, and was on his way down as we spoke. Much discussion focused on how to get me up to see the trees the following day. I assured Beto and Sra. Pintero that I was willing, able and prepared to hike up, but they were at least as skeptical of my hiking plans as Miguel.

While we waited for Moro to return Beto and Miguel and I discussed seed harvesting, and they showed me several baskets of collected nuts, some of them immersed in buckets of water. (Good seeds sink, bad ones float.) Beto scooped up a handful, then opened one, removing the nut and handing it to me. I stared at it for a moment in my palm. After all this research, effort and discussion of the Piñon Azul, it seemed almost disrespectful to pop it in my mouth. Miguel jerked me back to the present. “They’re edible, you know”, he said helpfully. Stammering that yes of course, I knew that, and feeling a bit foolish, I popped the nut in my mouth. It tasted like… a pine nut. Like a big pine nut, but without the occasionally less-than-perfect aftertaste that un-roasted pine nuts sometimes leave behind. We chatted a bit about eating the nuts. My hosts claimed to eat them only straight and raw, and were surprised to hear that Americans generally ate them roasted and as enhancement to other dishes, such as pasta or salads.

Finally, when it was completely dark, Moro arrived. A lean muscular 40-something with bright blue eyes and sandy blond hair, Moro looked something out of a Marlboro ad, with a broad-rimmed had, cowboy boots, oversized belt buckle and a drooping moustache that covered his mouth when closed. He had a firm, and very un-Mexican, handshake. (A typical Mexican handshake is soft, almost limp. When traveling in Mexico, I constantly have to remind myself not to crush hands when meeting people.) Moro bade us to sit back down, and pulled up a chair, received a summarized version who I was and what I was trying to do from Miguel, and then turned and conversed directly with me for a bit. Moro spoke little or no English, so the discussion was in my slow, plodding Spanish. He asked where I lived, what I did for a living, what brought me to Mexico, how I’d heard of the Blue Piñon, and about my trip to Juchipila. His tone was friendly and pleasant, but I had a clear sense of being checked out. After a few minutes he seemed satisfied, and I felt I’d passed whatever test had taken place. He turned to Beto and Miguel and began a discussion of how to best get me up the Mesa. It was agreed that Beto would take me up in a spare Jeep Cherokee owned by Miguel. The Cherokee had recently been rolled by Jose, and as a result had a dented and lowered roof, and no windshield, but Miguel assured us that it would carry us reliably up the mountain. We agreed that I’d meet Beto at 6:30 the following morning.

By this time I was ravenous, and to my relief, Miguel suggested that we get something to eat. Miguel, Beto (now wearing jeans and a T-shirt) and I bade Sr. and Sra. Pintero goodnight, and the three of us walked down the street to a local restaurant. As we walked, Miguel and I were conversing in English. Up till this point, I hadn’t heard Beto utter a word of English, so I turned to him and asked if he’d prefer that we spoke in Spanish. Beto replied in English, saying that wasn’t necessary. Though not nearly as fluent as Miguel, Beto’s English, like almost everybody’s in this town, was better than my Spanish.

As we walked, I learned Beto’s story. The youngest of the Pintero brothers, he’d spent the last dozen years working in California, where he’d married an American and fathered two children. Seven months ago, he and his wife had split up, and he’d returned to his hometown, leaving the children with her. He was staying with Moro and working for the family, helping supervise the construction of the mesa-top cabanas. Despite his sad story, Beto was perpetually upbeat, positive and smiling. We chatted a little about the demographics of Juchipila, and Beto shared that the trend of so many Juchipila-area men leaving to work in the U.S. had resulted in a surplus of young women, much to his delight.

The restaurant we ate in was a local spot I never would have found on my own. A seafood place on a second story corner about a block from the plaza, it was both cheap and excellent. While Miguel and I chatted over dinner, Beto, in the window seat, repeatedly whistled, smiled and waved at the small groups of young women who passed by below. Coming from another man in another place, his behavior might have seemed leering, but coming from good-natured Beto, in this small town where everyone knew everyone else, it seemed friendly, inoffensive and even charming.

Eventually I got around to asking Miguel about the mother of Miguel Jr. and Jose, and whether she was a part of their present lives. Miguel shared a long and painful story of his marriage to an American, their raising Miguel Jr. and Jose, her later challenges with depression and mental illness, and their eventual separation. Presently her whereabouts and welfare were both unknown and of concern to both Miguel and his sons.

After we finished dinner and walked back to Moro’s house, I thought we were done for the evening, but Miguel drove me across town in the rolled, windshield-less Cherokee to see Isaac, the eldest of the Pintero brothers. Isaac’s home was fronted by a gate with a buzzer, and when we were buzzed in by Isaac’s wife, we found ourselves walking into what felt more like a middle-class California home than a typical Mexican house. We waited for a bit in the living room while Isaac was summoned by his wife; Miguel seemed to think nothing of disturbing him without notice at 10PM to meet a gringo stranger.

Isaac met us and ushered into his study, which was filled with computer gear, photos, and a bookshelf full of books and papers. Isaac spoke little or no English, and Miguel translated for us for expedience’s sake. Isaac was formerly an engineer, and was now working apparently spending the bulk of his time working on his Cerro Piñones development/preservation project. His enthusiasm for his project and his fascination with the pines were immediately apparent. A fairly good amateur photographer, Isaac showed me dozens of photos on his PC of the piñones azules and Cerro Piñones in different lighting, seasons and weather conditions. I marveled at the beauty of a series of shots taken with a rainbow in the background, whereupon he promptly made me a CD of his library of blue piñon photos. Miguel and Isaac discussed the logistics for my excursion for the following day, and Isaac quickly offered an extra pickup truck for the trip, a vehicle in markedly better condition (including windshield) than Miguel’s Cherokee. We talked more about his property and plans for development and preservation, and we stepped over to the bookcase, where he showed me his substantial collection of books and botanical papers on the Martinez Piñon and Mexican flora in general. And there, in the middle of the middle shelf, I finally laid eyes on it: The Pines of Mexico and Central America by Jesse P. Perry, Jr. I switched to Spanish, blurting out how hard I’d looked for the book, and how valuable it was. Isaac responded, “Would you like me to make you a copy? We can have a copy made while you’re up on the Cerro Piñones with Beto.”

For a moment I was speechless. For two reasons: First, I was stunned. Not only had all of these people stopped what they were doing for the evening to help me, not only were they making available a vehicle and a guide for me without notice, now they were willing to have an entire book photocopied for my convenience.

Second, I was in an ethical quandary. In the real world, in my regular life, I’m the head of sales for a technology research firm that publishes and sells large numbers of written documents. My livelihood depends in no small part on strong U.S. copyright protections. Mexico is different. Whereas a local Kinko’s in the U.S. would typically refuse to photocopy a published book or other substantial amounts of copyrighted material, such flagrant copyright violations are routine in Mexico. Every Mexican town market features half a dozen stalls selling illegally copied CD’s of popular Mexican music for roughly US$2.00 a piece. (I’d already picked up a couple to relieve the solitary monotony of the autopistas.)

Miguel misinterpreted my surprise for miscomprehension, and repeated the offer in English. I quickly accepted, rationalizing to myself that the book was long since out of print.

Miguel and I left Isaac, driving back to his place in the Cherokee. I thanked him for all his help and efforts on my behalf, and headed back to the hotel for the night.

4 comments:

I'm all sucked into this story! Can't wait to read more tomorrow!

This story becomes amazinger and amazinger with each part - the gods or whatever were smiling on you!

regards--ted

Dear Watcher,

I came across your blog (and enjoyed reading it) while searching the internet for information on pinus maximartinezii on behalf of a German botanist who asked me to organize his visit to the region. Therefore, I would like to ask you, if you could possibly help me with contact details for Isaac Quintero in Juchipila, so that he might be so kind to "arrange" transport and a guide to Cerro Piñones.

Thank you very much beforehand for your help, Margarete

Hi Margarete, I'd be happy to help. I don't have contact info for Sr. Pintero, but I do for Miguel Lara, who can put you in touch with the right people in Juchipila. Email me directly (removing capital letters from the address) and I will reply with his info. adventureREMOVECAPSbotanist@yahoo.com

Post a Comment