Note: I started this as one post, but went off on so many tangents and rambled on for so long that I had to break it up into two. And the thing is, the point I really wanted to get to- the cool geological/hydrological origins of ponds and eskers in New England- I won’t get to till the second part. So the first part has a lot of forest-related stuff that may bore non-plant-geeks. But both parts have great tangents, so you should find something to keep you interested…

After a week and a half of bachelorhood, bike racing, mountain climbing and crazy work travel, I finally reunited with my family Tuesday evening at my parents place in the suburbs of Boston, where Awesome Wife and the Trifecta had been visiting since last weekend. The next morning we loaded up ourselves and a subset of our luggage in one of their cars and headed North.

After a week and a half of bachelorhood, bike racing, mountain climbing and crazy work travel, I finally reunited with my family Tuesday evening at my parents place in the suburbs of Boston, where Awesome Wife and the Trifecta had been visiting since last weekend. The next morning we loaded up ourselves and a subset of our luggage in one of their cars and headed North.

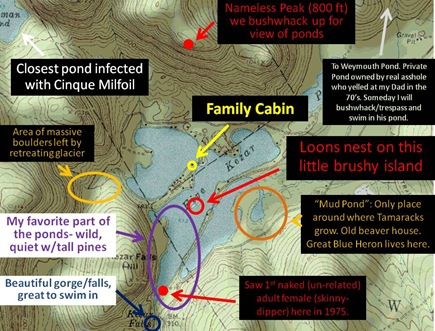

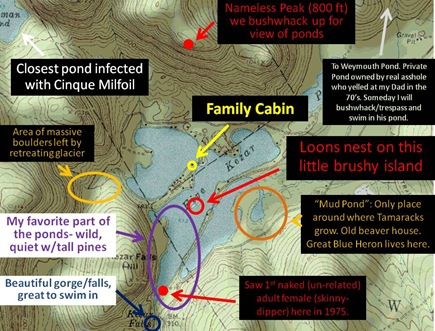

I blogged about our family’s cabin on a lake in the Maine woods last summer. You can go check out that post for background and basic tree info if you like. In this post I’m going to focus more on the big picture: the retreat of the glaciers, and how it shaped both the forests and the hydrology of Western Maine, and our lake in particular. If all goes well, I’ll pick up this glacier-theme again on our next family vacation, which begins- no I am not kidding- later this week.

The Golden Age Of Family Vacations

Tangent: But first, let’s talk about my family and vacations. I truly believe that now- right now- is the best time we’ll ever have to do family vacations, and here’s why: our kids are the perfect ages. Bird Whisperer is 10, and the twins will be 8 the end of this month. That means that all of our kids are old enough to a) be out of diapers, b) tolerate (and entertain themselves during) long car/plane trips, c) not throw tantrums every 20 minutes, d) not require constant oversight/supervision, e) display a modicum of good manners when we’re guests at family/friends, f) have enough physical stamina for hiking, canoeing etc., and g*) have enough world-awareness to possibly have some interest in, and learn a bit about, the stuff we’re seeing.

*”g”? Really? I got up to “g”? OK, this enumeration thing is starting to read like a cry for help… Like I need a 12-step program or something. Except that of course would be even more enumeration…

But most importantly- and this is the key point* I have been enumerating my way up to- they don’t hate us yet. You know what I’m talking about. Even if you don’t have kids, you’ve been a kid, and you know that all kids are genetically programmed to hate their parents between the ages of 13 and 22. Then family road-trips suddenly transmogrify into these little self-contained nomadic enclaves of hostility, tension and Freudian baggage, and that’s why Awesome Wife and I are packing in as many great family vacations as we can right now. Because this- right here, right now- is the Golden Age of our nuclear family.

But most importantly- and this is the key point* I have been enumerating my way up to- they don’t hate us yet. You know what I’m talking about. Even if you don’t have kids, you’ve been a kid, and you know that all kids are genetically programmed to hate their parents between the ages of 13 and 22. Then family road-trips suddenly transmogrify into these little self-contained nomadic enclaves of hostility, tension and Freudian baggage, and that’s why Awesome Wife and I are packing in as many great family vacations as we can right now. Because this- right here, right now- is the Golden Age of our nuclear family.

*So I guess this would be “h”.

Nested Tangent: One more reason why this is the Golden Age: Because Awesome Wife and I still have our health, mental acuity and fitness. Oh, someday our kids will like us again, and maybe even want to vacation with us. But we’ll probably be somewhat more frail and not quite as up for adventure and exertion and such. And of course we probably won’t be as fun to vacation with, what with our frequent recitation of our various ailments, our untimely gaseous emissions and our near-constant complaining of how the succeeding generation lacks the experience and values that made our generation so great*.

*Because every generation of geezers always says this about the next generation, no matter how heinously that particular generation of geezers actually behaved in their prime…

So I guess my point here is, if you have kids in the Golden Age, don’t wait. Go on vacation- like now.

As I mentioned in last year’s post, I spent many, many summers on the lake as a boy/teenager, and it’s my absolute favorite place to visit when I return home.  But now that I’ve been away for almost 20 years, it’s both familiar and strange at the same time. Last year I focused on IDing a number of trees, and I did so again this year. Poking around in the Maine woods, everything is different than Utah- different trees, lichens, mosses (pic right), birds- you name it. But this visit I focused less on the individual species, and more on the natural history/big picture of the lake.

But now that I’ve been away for almost 20 years, it’s both familiar and strange at the same time. Last year I focused on IDing a number of trees, and I did so again this year. Poking around in the Maine woods, everything is different than Utah- different trees, lichens, mosses (pic right), birds- you name it. But this visit I focused less on the individual species, and more on the natural history/big picture of the lake.

There are 2 huge differences between Maine and Utah- forest and lakes. Let’s talk about forest first.

Forests East & West

When you live out West, you come to naturally think of forests as being associated with altitude and mountains. If you live in Utah or Colorado or Arizona or even California, forests are generally something you go up into*. But in the East, forests are the default state in the lowlands. You don’t go up into them- they just take over pretty much any patch of land that doesn’t get built or mowed for the last 20 years. This means that there’s a lot more forest in the East than in the West. And- and I’ll bet you didn’t know this- the most heavily-forested American state is- not Washington, not Alaska, not Oregon, not Georgia- it’s Maine. Over 90% of Maine is forested.

When you live out West, you come to naturally think of forests as being associated with altitude and mountains. If you live in Utah or Colorado or Arizona or even California, forests are generally something you go up into*. But in the East, forests are the default state in the lowlands. You don’t go up into them- they just take over pretty much any patch of land that doesn’t get built or mowed for the last 20 years. This means that there’s a lot more forest in the East than in the West. And- and I’ll bet you didn’t know this- the most heavily-forested American state is- not Washington, not Alaska, not Oregon, not Georgia- it’s Maine. Over 90% of Maine is forested.

*Northwest readers may feel differently, but their lush lowland forests dominate only in the narrow coastal strip West of the Cascades. East of the Cascades, the altitude-forest connection holds.

Tangent: Interestingly though, this wasn’t always the case in recent times. In the early 19th century far less of the state was forested, as much of the woods were cleared for agriculture. In the mid-1800’s, as land in the mid-west opened up, thousands of Maine farmers abandoned their rock-strewn fields for the rich (and relatively rock-free) topsoil of the mid-west. Today, as you drive or bike back roads around the state, you’ll often noticed low, crude stone walls in the forest, where farmers deposited the larger stones they removed from their fields. (pic right = old stone wall, behind the ferns)

Tangent: Interestingly though, this wasn’t always the case in recent times. In the early 19th century far less of the state was forested, as much of the woods were cleared for agriculture. In the mid-1800’s, as land in the mid-west opened up, thousands of Maine farmers abandoned their rock-strewn fields for the rich (and relatively rock-free) topsoil of the mid-west. Today, as you drive or bike back roads around the state, you’ll often noticed low, crude stone walls in the forest, where farmers deposited the larger stones they removed from their fields. (pic right = old stone wall, behind the ferns)

The largest forest-type in North America is the continent-spanning, species-poor Boreal Forest, which I’ve mentioned previously. The second largest is the Eastern Deciduous Forest, which spans from Massachusetts to Missouri, reaches North up to Southern Michigan and extreme Southern Ontario, and is rich in diversity, with over 200 native tree species. Sandwiched in between these 2, including elements of both, but not quite like either, is the Laurentian Mixed Forest, and this is the forest type that blankets Maine.

The largest forest-type in North America is the continent-spanning, species-poor Boreal Forest, which I’ve mentioned previously. The second largest is the Eastern Deciduous Forest, which spans from Massachusetts to Missouri, reaches North up to Southern Michigan and extreme Southern Ontario, and is rich in diversity, with over 200 native tree species. Sandwiched in between these 2, including elements of both, but not quite like either, is the Laurentian Mixed Forest, and this is the forest type that blankets Maine.

As the glaciers retreated from Maine 12,000 – 14,000 years ago, forests returned to Maine in more or less 3 waves. The first wave, consisting primarily of Spruce (Red, White Black) and Fir (Balsam) was somewhat Boreal in nature. Today these trees are common only at higher elevations or in the far Northern reaches of the state.

As the glaciers retreated from Maine 12,000 – 14,000 years ago, forests returned to Maine in more or less 3 waves. The first wave, consisting primarily of Spruce (Red, White Black) and Fir (Balsam) was somewhat Boreal in nature. Today these trees are common only at higher elevations or in the far Northern reaches of the state.

Side Note: On this trip I finally spotted a couple of Spruces at lake level, over by the Mud Pond. Otherwise they’re absent from the immediate vicinity of our lakes.

The second wave included White Pine and the Birches (pic above, right) (Paper, Gray, Yellow), and the third wave the various Maples (Sugar, Striped) Beech and Oak (Northern Red*.)

The second wave included White Pine and the Birches (pic above, right) (Paper, Gray, Yellow), and the third wave the various Maples (Sugar, Striped) Beech and Oak (Northern Red*.)

*Almost all Oak I’ve spotted in Maine is Quercus Rubra, Northern Red Oak (pic above, left). Very occasionally I’ve spotted Q. Alba, White Oak (pic right), up here, which is quite common just down in Massachusetts.

*Almost all Oak I’ve spotted in Maine is Quercus Rubra, Northern Red Oak (pic above, left). Very occasionally I’ve spotted Q. Alba, White Oak (pic right), up here, which is quite common just down in Massachusetts.

Side Note: I don’t know which “wave” Eastern Hemlock (pic right) was a part of. I’m pretty certain it wasn’t the first, only because the Northern limit of its range is only a hundred miles or so past the Canadian border. I sort of suspect it was in the second, mainly because Mountain Hemlock always seems to occur alongside pines in the Sierra. But this is a total guess.

Side Note: I don’t know which “wave” Eastern Hemlock (pic right) was a part of. I’m pretty certain it wasn’t the first, only because the Northern limit of its range is only a hundred miles or so past the Canadian border. I sort of suspect it was in the second, mainly because Mountain Hemlock always seems to occur alongside pines in the Sierra. But this is a total guess.

On the ground, the transitional nature of the Laurentian Mixed Forest is most obvious in the mix of conifers and hardwoods. Throughout Maine, largely independent of aspect and elevation, you’re usually within a few yards of Pine, Hemlock, Oak, Beech and Maple, and all freely intermingle around the lakes. (pic left = Northern Red Oak and Eastern White Pine) To the North, up in Newfoundland and Central Quebec, the Boreal Forest is mainly coniferous. Down just in Pennsylvania or Kentucky, the Eastern Deciduous Forest is… yes, that’s right, deciduous.

On the ground, the transitional nature of the Laurentian Mixed Forest is most obvious in the mix of conifers and hardwoods. Throughout Maine, largely independent of aspect and elevation, you’re usually within a few yards of Pine, Hemlock, Oak, Beech and Maple, and all freely intermingle around the lakes. (pic left = Northern Red Oak and Eastern White Pine) To the North, up in Newfoundland and Central Quebec, the Boreal Forest is mainly coniferous. Down just in Pennsylvania or Kentucky, the Eastern Deciduous Forest is… yes, that’s right, deciduous.

Freaky-Cool Plant-Geek Tangent For Possible Future Vacation

Tangent: One of the most interesting forested areas of the Northeast, that I didn’t make it to this trip, but hope to visit on the same trip next year (and in fact Awesome Wife and the Trifecta were right there the 1st week of their vacation), is- believe it or not- Southern New Jersey, specifically the Pine Barrens. This area- which I Airplane-Seatmate-Botanist-Wade told me about last week on our flight to Atlanta- is actually an extension of the next forest type to the South- the Southern Oak-Hickory-Pine Forest, which is what you fins in the mid (non mountain or coastal) regions of the Carolinas, for instance. But a finger of this forest type actually extends clear up into Southern New Jersey. It’s like a little botanical piece of Dixie sandwiched in between Philadelphia and Atlantic City!

Nested Tangent: Even freakier, the absolute Northernmost extension of the Southern Oak-Hickory-Pine Forest is- are you ready?- Long Island. That’s right, the native forest of Long Island has more in common with the Carolinas and Northwestern Georgia than it does with Maine or Vermont. Long Island of course is pretty built up and I’m not exactly sure where one finds native forest on Long Island nowadays, but… anyway, it’s a good teaser for a future trip/project.

Nested Tangent: Even freakier, the absolute Northernmost extension of the Southern Oak-Hickory-Pine Forest is- are you ready?- Long Island. That’s right, the native forest of Long Island has more in common with the Carolinas and Northwestern Georgia than it does with Maine or Vermont. Long Island of course is pretty built up and I’m not exactly sure where one finds native forest on Long Island nowadays, but… anyway, it’s a good teaser for a future trip/project.

This common, casual mix of conifers and hardwoods is uncommon in the West. In the Wasatch, one is either in coniferous or deciduous- specifically Aspen- forest. Where the 2 types mix, it usually means you’re in a transitional zone, where Firs or Douglas Firs, for example, are in the process of invading- and eventually dominating- an Aspen stand.

This common, casual mix of conifers and hardwoods is uncommon in the West. In the Wasatch, one is either in coniferous or deciduous- specifically Aspen- forest. Where the 2 types mix, it usually means you’re in a transitional zone, where Firs or Douglas Firs, for example, are in the process of invading- and eventually dominating- an Aspen stand.

The glaciers left behind all sorts of rocky debris, which made Maine so miserable for farming. The same debris greatly affects drainage, and this is why so much of the Maine woods is so darn wet and boggy. (It’s also why there are so many darn mosquitoes. Holy crap- a couple of times I thought they were going to pick us up and carry us away.) The wetness of the forest floor results in thick- often impenetrable- ground-cover, one common element of which is ferns.

I talked about Ferns and how cool they are back in March, when I checked out Fern Trees down in Costa Rica. Quick recap: They’re way neat because they’re sort of in between lycophytes and seed plants in that they’ve evolved leaves, but not seeds. They employ- like mosses and lycophytes- an alternating-generation strategy in which the thing you think of as “a fern” is the gametophyte or haploid generation, which is succeeded by the fully diploid (and morphologically way, way totally different) sporophyte generation.

I talked about Ferns and how cool they are back in March, when I checked out Fern Trees down in Costa Rica. Quick recap: They’re way neat because they’re sort of in between lycophytes and seed plants in that they’ve evolved leaves, but not seeds. They employ- like mosses and lycophytes- an alternating-generation strategy in which the thing you think of as “a fern” is the gametophyte or haploid generation, which is succeeded by the fully diploid (and morphologically way, way totally different) sporophyte generation.  Like their more primitive cousins, they never evolved pollen; they produce actual sperm, which swim to the eggs* on other gametophyte ferns, and this is another reason why ferns are typically found in damp places- you need water to swim. Speaking of water, this brings me to the thing about this vacation that I really want to blog about-

Like their more primitive cousins, they never evolved pollen; they produce actual sperm, which swim to the eggs* on other gametophyte ferns, and this is another reason why ferns are typically found in damp places- you need water to swim. Speaking of water, this brings me to the thing about this vacation that I really want to blog about-

*Which are contained in flask-like structures called archegonium.

Tangent: I actually found a key for New England Ferns, but ran out of time to do a species ID of the fern pictured in the 2 shots above. Yeah that’s right, I ran out of time. When you envision your vacation, you always imagine all this free time, lazing around, but when you fit in all the travel logistics and activities and what-not, vacations are really busy! Good to be back at home and work- maybe I can catch up on my rest…

Anyway, I suspect it’s something in the genus Thelypteris (maybe Marsh Fern), but it’ll have to wait for either a) my next trip to Maine or b) the next time I am bed-ridden with death flu and have time to poke around at old pics…

Next Up: Lakes, Ponds, Glaciers and the Fabulous Hydrology of Western Maine .

Southern Nj, eastern long island and cape cod have a pine-oak forest type with the majority of the pines being pitch pine. So i wouldnt call it a southern pine forest since pitch pine isnt a southern species of pine.

ReplyDelete