*Yes, I am just blogging about what I did last Sunday now. I am always behind in this project…

**The series included my subsequent discoveries of 2 more such hybrids, which I posted about here and here, as well as my introduction to Rudy, which I posted about here. I later posted here about my scramble to probably the most dramatically-situated of the hybrids, which Rudy initially discovered over 50 years ago.

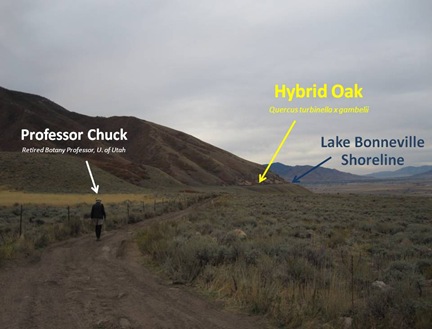

Late last Fall, Rudy and Professor Chuck re-discovered another such hybrid, which Rudy had discovered in the late 1950s, but subsequently “lost” and omitted from his thesis. Sunday we returned so that I could get a GPS reading and some sample leaves.

Hike

Accessing the hybrid required an easy 4 mile round-trip hike along the old Bonneville shoreline-bench on the West slope of the Oquirrhs. Rudy waited at the car while Professor Chuck and I made the hike.

Tree

*Yes, I realize this is exactly the kind of over-the-top boosterism I was poo-pooing in Wednesday’s post, but damnit it’s true. As Stegner wrote, “It is a land that breeds the impossible.”

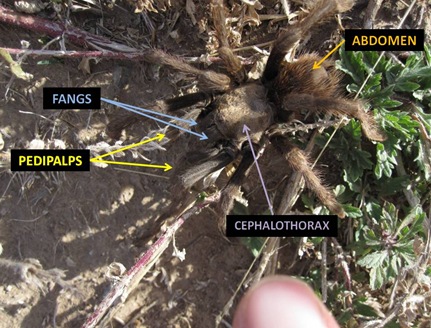

We walked back, chatting about plants and moss and range condition* and the day grew warmer. A gopher snake slithered across the old 2-track we were following, and then a moment later I saw it- a nice, big Tarantula.

Spider!

Utah certainly has many animals I never saw in the wild growing up in New England. Mountain Lions, Elk, Coyotes, Bobcats, Golden Eagles, Magpies, Pronghorns, Buffalo- I never saw any of them in the wild before I moved out West. But of all the wild animals I’ve seen since moving here, I don’t think any freaks me out more than a tarantula.

*These are also called whipscorpions, but I get a kick out of “vinegaroon.” Sounds like some weird kind of cookie.

** These are not the same as scorpions. Completely different kind of critter.

*** Nope. Not scorpions either.

****Called “Harvestmen” in much of the non-US English-speaking world. BTW, these are (I believe) the subject of Christopher’s studies over at CoO.

Arachnids have a distinctive two-chunk body-form: the cephalothorax, which is a combo head and thorax and to which the legs are attached, and the abdomen.

Detail Tangent: This is a good time to talk about why “bugs” don’t usually get all that big. An exoskeleton is a very efficient support structure for very small animals, and offers protection against both predators and dessication (drying out.) But it’s got a big disadvantage: as the animal gets bigger, the exoskeleton required to support it and house the increased musculature needed to move it, becomes too heavy and cumbersome*.

*Yet another disadvantage to exoskeletons is the whole molting-hassle.

With an internal skeleton, this isn’t nearly as much of a problem.

So skeletal mass and bulk is a size-limiter for “bugs”. But interestingly, the more important limiter- in that it becomes a problem sooner as a “bug” gets bigger- may be respiration. Insects don’t have lungs as we think of them.

*What, you think I have all day to sit around and draw pictures?

**Bug-blood. Confusingly, many other arachnids, like mites and Daddy-Longlegs, have trachea instead of book lungs.

Another unresolved issue is how many times arachnids evolved from water to land. Do all land-based arachnids* share a common terrestrial pioneer ancestor, which accounts for some of their common features, such as book lungs? Or did things like books lungs evolve multiple times independently in different pioneer-ancestors**?

*Aquatic spiders BTW are descended from land-based spiders that returned to the water, analogous to whales or seals.

**In which case these features would be analogous to Old/New World Vultures, C4 and CAM photosynthesis, isoprene emission in plants and about a zillion other things we’ve looked at in this blog. Isn’t it cool how the same or similar features keep evolving over and over again?

*Although some spiders, including tarantulas, also do a bit of tearing and chewing with their fangs, and also grinding-up of food with their pedipalps.

Tangent: This is a good point to get back to the whole bug-eats-mammal, thing, because Bird Whisperer and I just saw this darn near happen last week, when we watched Return Of The King.

*Oh yeah, and she’s way too big, too; she couldn’t breathe or walk, though maybe she’s just powered by some kind of physics-defying Magic Malice or something…

There are at least 40,000 known species of spider, some 900 of which are tarantulas, occurring on every continent except Antarctica. Most live in underground burrows and wait for prey to pass by. Many surround the burrow with a “welcome mat” of silk threads that alert it to passing prey.

It’s thought that in the Fall males go wandering in search of mates. I’ve mostly seen them down in the foothills, around 5,000 feet, but I spotted one a few years back up by Jeremy Ranch, at nearly 7,000 feet. (The only place I’ve seen a tarantula twice around here is crossing the “paved” road of Mill Creek Canyon, about 100 feet below the entry-fee station, both times- that’s right- in October.)

Side Note: Speaking of males on the prowl, tarantula mating is pretty weird. The male spins a web and deposits a sperm packet on the surface. He then picks up the sperm with his pedipalps and attempts to insert it into the female genital opening. Successful or no, he runs a decent chance of getting eaten by the female.

Tarantulas have few natural enemies; a notable exception is the Tarantula Hawk, Pepsis sp. a wasp which stings, paralyzes and then lays its eggs within the spider’s body. The eggs hatch and consume the still-living-but-paralyzed spider from the inside-out. Interestingly, though I’ve seen Tarantula Hawks many times in Southern Utah and even in Costa Rica, I’ve never seen one in Northern Utah.

Fangs are the tarantula’s offensive weapon, and they’re used defensively as well. The fangs, BTW, move up and down, unlike most spiders, whose move side-to side. But a tarantula’s bite, though painful*, isn’t all that dangerous; there’s no record I could find of anyone dying from a bite.

*But nowhere near as painful as the sting of a Tarantula Hawk, which is apparently out-of-this-world-awful.

But the primary defensive weapon of New World Tarantulas, including A. iodius, isn’t venom; it’s hair.

All New World Tarantulas have what are called urticating hairs*, which are specialized barbed hairs that rub off easily and can embed in the skin or eyes of other animals. When embedded in skin, they can cause significant irritations; when embedded in eyes or mucous membranes* they can cause extreme irritation, and even death in small animals through edema. The level of irritation varies across species. The urticating hairs of the South American Goliath Birdeater, Theraposa blondi, cause a rash that supposedly feels like “shards of fiberglass.” But the only firsthand description I could find of the irritation caused by A. iodius hairs described it as “15 minutes of minor irritation.” There also seems to be a range in severity of the reaction depending on the individual afflicted, and it now seems as though the irritation may have a chemical component in addition to the mechanical one.

*A number of caterpillars also have urticating hairs, which they of course evolved completely independently. That’s right- yet another example of convergent evolution!

**The hairs can get in the lungs of small mammals, though there’s no known case of this occurring with humans.

Most hairs on a tarantula are not urticating; they’re just body hairs*. Urticating hairs on most species, including A. iodius, grow only on the top of the abdomen.

*It’s not clear what purpose the body hairs serve.

There are 2 really cool things about urticating hairs, each of which relates to another animal we’ve looked at previously.

Last month when we looked at porcupines, I noted that porcupines don’t actually “throw” their quills. But tarantulas do. When threatened, a tarantula will spin around to face its attacker, and then use its 2 rear legs to brush urticating hairs off its abdomen in the direction of its attacker!

The second cool thing relates back to Black Widows, which I blogged about way, way back when, long before anyone ever read this blog*. You can go check out that post if you like, but the Readers Digest version is this: black widow venom contains at least 7 different toxins, specifically targeted towards different kinds of prey and/or predators- 5 for arthropods, 1 for vertebrates (i.e.us) and 1 for crustaceans (i.e. woodlice.)

*I’m serious. Like no one read it back then.

Side Note: I had a really tough time determining for this post how many urticating hair types a given species has. Best as I can tell, the minimum is 1, the maximum may be as high as 4.

Type 3 and 4 hairs appear to be most irritating to mammals, and type 3 appears to be effective against both vertebrates (you, your dog, your ex-spouse) and invertebrates (bugs). The urticating hairs on A. iodius are Type 3. So while you don’t need run away from a Tarantula in the Wasatch or the Oquirrhs, I don’t know that I’d go picking it up.

Professor Chuck patiently waited while I examined poked, prodded, filmed (but didn’t touch!) A. iodius. After a bit, we finished the hike back, rejoined Rudy, and drove back home, passing and noting 3 other (previously-visited) hybrids en route. October’s a great time to spot both hybrid oaks and tarantulas in Northern Utah. Keep your eyes open.

15 comments:

The only time I've ever seen tarantulas was driving through west Texas a few years ago. I wouldn't have noticed them except my friends informed me that the lumps moving across the highway were, in fact, giant spiders. They refused to stop.

I may need new friends.

Great post, Watcher... I do enjoy spiders, usually from a relative distance, and I have noticed (but, of course, never as thoroughly researched) the irritation of the hairs from the museum tarantula.

If you'll allow a small quibble, the labeled photo shorts the critter on a pair of legs. I think the fangs are not visible from above, and the pedipalps are the first visible pair in your photo. The fangs are hard (chitin?), very sharp, and visible only underneath. But check with your experts...

Marissa-- I've heard of such tarantula migrations, but most thankfully, never encountered one!

Here's my theory for why tarantulas are hairy: to look scarier/bigger.

Spiders are fascinating. There's something creepy and mesmerizing about their leg movement as they walk.

Have any hybrid oaks been found in Utah County? I'll keep a look out for them.

OK, I am officially creeped out. Just reading about spiders gives me the willies.

Do you know if tarantulas can raise up their two front legs as a defensive posture? I was riding last fall on a dirt road and saw a large spider about the size of my fist or a little larger. When I stopped, it raised its two legs and charged me. I got the heck out of there! Someone told me they thought it was a wolf spider but it looked more like a tarantula.

mtb w (the w in this case stands for wuss)

Marissa- when researching the post I kept coming across references to these whopper Fall migrations in Texas; sounds like you were lucky enough to see one! I guess too there’s a bit of debate about the reasons behind them- some folks have speculated that it may be more of a migration than a mating thing, but the mating answer still seems to be the general consensus.

Sally- Thanks for the correction! Instead of “fangs” I probably should have said “chelicerae”; the actual pointy/jabby parts are underneath. But I think I got the pedipalps part right. Here’s another shot I found with better labeling.

Kris- Good theory. For some reason, the body hairs creep me out more than a “bare” exoskeleton- don’t know why…

And yes! There are several great hybrid oaks in Utah County. Alpine has at least 4 great ones (a couple within a mile of Fatty’s house) and there’s another smaller on the bench just above Cedar Hills. Sometime if we meet up for a ride down your way we can take an extra 30 minutes and do a drive-by of a couple.

mtb w- So first off, any spider in CO as big as your fist was absolutely a tarantula. And second- are you serious? It charged you??

It was brown and the body was approximately 2 1/2 to 3 inches long (including both the abodomen and cephalothorax, although I didn't exactly stick around to put a tape measure to it), plus ginormous legs.

Yeah, when I stopped to look at, it charged me with its two front legs up. It moved fairly quick, not like the one in the video you shot. It moved maybe a foot towards me b/f I got pedaling again. It was a pretty aggressive sucker - it wasn't tame like the one in the Hawaii episode of the Brady Bunch!

mtb w

City Creek seems particularly rich in tarantulas; once, perhaps five years ago, I rode the canyon when the little buggers were so thick on the road that I was unable to avoid squashing several. Being rather bug-phobic and (at that time) unaware that tarantulas were native to Utah I was officially *freaked out*.

// City Creek is also super rattlesnake heavy in summer. Never had to dodge a rattlesnake in any other Wasatch Front canyon.

// Also nearly hit Orin Hatch in City Creek once.

W-- You're right, I counted wrong. Shoulda put my glasses on. But are you saying the chelicerae are the fangs? I'm confused... I always thought of it as some kind of mustache. [grin]

I always stop for photos of tarantulas when I see them. They are too slow to avoid the photo, and too crazy big and fascinating not to take photos of.

At least 3-4 times a year, we have a tarantula alert at the house and all the kids and I go out and play with one someone has found. (but we don't touch it)

We used to see them on the edge of the roads near the Sierra (central California, around Kings Canyon) in the Sept/October timeframe, too.

They did not seem to venture into the flat emptiness around Fresno. Instead, we got dozens of black widows living all around our house (backyard, external doorways). As a result, that's the only species of spider I'm truly comfortable identifying and subsequently squashing.

Too. Many. Spiders.

I've barely recovered from the Christmas stocking incident of 1973 as it is.

It's payback isn't it? Payback for inadvertently outing your blog?

I'm going off to look at pictures of Phil's giant baby and think happy thoughts.

Good timing on the post. I saw three tarantulas on the trails this weekend.

Awesome spider post - I learned stuff.

I seem to recall the taxonomy of the genus Aphonopelma is rather confused - seems odd given their popularity.

I've got a few pics of one I saw in western Oklahoma that will find their way onto my blog - hopefully sometime soon. (You think you're always behind in this project, I'm just now posting about stuff I saw in Florida almost 3 months ago!)

I haven't seen any tarantulas here in Oregon, but we do have Gigantic House Spiders-- and I do mean GIGANTIC. Apparently if you see one on the move, it's a male looking for a female. And my house is apparently the best place for the males to try to find females.

I call them "kung fu fighting spiders" because they will put their front legs up when you come at them-- like they're saying, "come get some, sucker, I'll karate chop you so hard". I'm afraid they're going to grab whatever I'm weilding and use it against me.

I took a somewhat crappy picture of a massive one the other day, I'll see if I can't send it over to you, Watcher.

Great post. I like spiders and agree with Kanyon Kris that it is mesmerizing to watch them move. An ex-boyfriend once kept a tarantula as a "pet" in a coffee table he had built sides on and covered with a glass top. We used to take it out at parties and let it walk on our arms. I didn't realize it could have thrown irritating hairs into my eyes. The stupid things we do in college.

I just read that the only known vegetarian species of spider has recently been identified. It is Bagheera kiplingi, a jumping spider that lives in Costa Rica. It eats the protein-rich tips of acacia plants. It has to hunt for its plant food because there is a type of ant that guards that same food. The article said that in an ecosystem full of plants but swarming with other spiders and insects that are competing for food, this is a case for evolution from hunter to gatherer for sure.

Post a Comment