It’s been a busy several weeks. After I came home from the conference in San Diego, I spent a weekend at home alone (AW and the Trifecta were visiting family in New Jersey) racing and getting ready for my next trip. Monday morning before heading to the airport I wanted to sneak in a quick ride. Lacking time to drive up one of the canyons, and wanting to ride the mtn bike, I rode the Shoreline Trail for the first time in 2 months.

Side Note: The race was the Tour de Park City, a race I’ve shined in the last 2 years. This year it sucked for me, which is par for the course for me racing

*Fortunately I race with full-finger gloves, and so couldn’t see the extent of the damage until after the finish line. The following morning I got to work on some overdue mtn bike maintenance, and I just want to point out what a phenomenal dick-dance it is to install grips with a massive bandage on your good hand…

I’ve been mtn biking a lot this summer, but riding practically everything except Shoreline. By late May, when trails up in Park City and Jeremy Ranch start opening up, I’m usually a bit tired of the open foothills, and drawn to the cool, shady forests that I can only ride in for 4 or 5 months of the year. So returning to Shoreline was a bit of a shock. Last time I rode it, it looked like this.

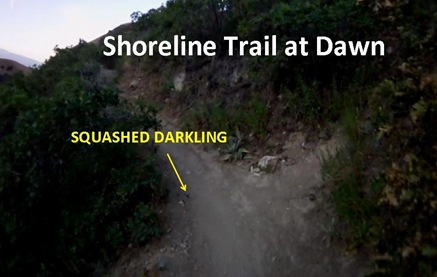

Last Monday, it looked like this.

Even though it was still early and cool, it just looked hot. The slopes were littered with wilted Balsamroot and Arnica leaves, the successive waves of yellow blooms long past. The Oak leaves, soft and lime green on my last ride, were dark and leathery. Everything seemed dry, brittle, dusty and brown. With still several weeks of summer left, I felt a bit deflated, that another season had passed, that I’d missed a good part of the explosive waves of summer blooms, and was now riding through the leftovers and wreckage of the party I’d somehow missed.

But “missed” is all relative, isn’t it? I pay as much or more attention to the blooms, and the natural world in general, as any mtn biker I know, but what has slowly dawned on me over the 3 summers on this project is that I’ll never get the sense of capturing it all. There will always be a million things I don’t get a chance to check out or even notice, and somehow that’s both inspiring and disappointing at the same time.

Of course stuff is still happening throughout the summer, and once I got past the surprise, wistfulness and initial self-pity-party of the dry, brown foothills, I started to pay attention.

Gumweed is one of those plants that looks like a gnarly, bristly weed, and to a large extent it is. Gnarly and bristly, anyway; we’ll get to the “weed” part in a moment. Livestock and wildlife don’t eat it except as a last resort, not so much because it’s bristly, but more so because it’s packed with tannins and resins and such that make it difficult to stomach.

But Gumweed was first catalogued by Lewis and Clark on the high plains, long before it likely would’ve spread so far West via Euromerican introduction, and as best I can tell it seems that Gumweed is native East of the Rockies, but is an exotic to the West of them. So, like the Brown-Headed Cowbird, Gumweed appears to be a North American native that has greatly expanded its range as a result of human settlement and activity.

Foothill Massacre

This time of year the Shoreline trail- should you bother to look down- is fairly littered with corpses. Trampled in the dust, every couple dozen feet or so, you’re likely to spot a crumpled up black exoskeleton- the remains of a crushed Darkling Beetle, Eleodes obscurus.

*Yes, yet anther way cool example of convergent evolution.

Side Note: So far as I know, the spray isn’t harmful to us, though one source mentioned stinky fingers following handling. Just the same, I wouldn’t hold its butt up to your eye…

When Mice Go Bad

This chemical defense isn’t always effective. At least one predator, the Grasshopper Mouse, has developed a well-executed technique of rapidly grabbing the poor beetle and jamming its butt in the ground, where the spray squirts harmlessly. But it works well enough that the standard first defensive move of a threatened Darkling is to stop still and raise the rear tip of its abdomen.

Tangent: I usually try to stick to blogging about things I’ve actually come across, but the Grasshopper Mouse is so Phenomenally Way Cool I’m making an exception. Imagine if you took a mouse* and somehow suped it up. Gave it bigger, sharper teeth, stronger jaw muscles, longer fingers and claws for grasping and handling prey. And then this mouse ran around and actively hunted for a living, going after not just insects, but snakes, scorpions, lizards and even other mice (yikes!) A truly carnivorous mouse- wouldn’t that be way cool?

*Just so as to not give the wrong impression, the Grasshopper Mouse isn’t all that closely-related to the Common House Mouse, Mus musculus. So it’s not like some House Mouse just suddenly mutated and turned all evil and scary and everything.

Wait- it gets better. O. torridus, like larger carnivores,

O. torridus is One Cool Mouse, and has catapulted to the top of my Critters I’m Dying to Spot list.

It works well enough that supposedly* some number of similar-looking beetles actually mimic the behavior, stopping still and

*I only found reference to this in one source- Field Guide to the Sandia Mountains, Robert Julyan & Mary Stuever, and was unable to find examples of the mimic-species.

** Actually used this photo last year, don’t have the source.

This Freeze-and-Prepare-to-Spray defense is probably the worst possible response to an approaching human foot or mtn bike tire.

Tangent: This raises the whole fascinating issue on how roadkill might impact the evolution of various road-crossing critters over coming centuries (assuming cars are around that long.) There are far more roads than there are high-traffic singletracks, and one wonders what selection pressures automobile traffic is putting on critters like deer, rabbits, squirrels, coyotes and such. One would think (and this is pure conjecture here) that modest-brained critters would be likelier to evolve a general avoidance of asphalt more quickly than the ability to judge/gauge oncoming traffic, and so that the selected survival trait would not be so much a new ability or instinct for automobile-dodging as it would be effective isolation of populations within road-bounded “islands”, creating a new de facto “island biogeography”, like the desert-isolated mountain ranges of the Great Basin. Are Aberts Squirrel-style stories of speciation happening all around us right now as a result of roadkill?

In any case, I do my best to avoid running over Darklings. One beetle here or there certainly won’t make a difference in the big scheme of things, and they clearly don’t have much in the way of brains, or likely any kind of self-awareness. But the purpose-driven lives* of so many bugs convinces me that in their own, minimal consciousness kind of way, they “want” to live at least as much as I do, and if it turned out that there were some uber-aware, higher-state-of-consciousness thing/force in the world/universe that somehow perceived reality far above and beyond that which we’re aware of, I’d hope it wouldn’t just squash me out of laziness or convenience.

*Been itching to co-opt that term.

Stem is too long and I still can't believe that is a 2.4:)

ReplyDeleteOur Gerbil simply pounces on and loves to eat as many invertebrates (specifically crickets) that the kids can feed it. Who knew they so fierce?

Since when does Carbon fatigue?...I need to read the post. I didn't think it really did.

We have lost of Stink beetles, as well as big, fast moving beetles similar to the stinky ones except not as smooth and glossy with more defined body segments and run quite fast.

PS: Tarantula migration time is here for us and I frequently seem them road killed on the trails right now.

Probably my most random comment. I am obviously interested in the finger post. Finger tip injuries are one of the best healing of all injuries if you can keep a surgeon away from them.

Fatigue isn't what concerns me about carbon fiber composites. And as Enel noted, they don't fatigue (for all practical considerations).

ReplyDeleteI don't like carbon because it usually fails catastrophically (whereas metal will often bend first), determining if a carbon component is damaged / dangerous is not as easy as metal, proper installation is critical, and often there is no weight savings or it's insignificant.

Here's my post Watcher referred to:

http://kanyonkris.blogspot.com/2010/07/reducing-my-carbon-footprint.html

Loved learning about the beetles and mice. Flower was cool too. I'm spending too much time on the road--no cool plants that grow in asphalt, though a few weeds are poking through the cracks in my driveway.

ReplyDeleteCould have saved you the cost of the aluminum bar by lending you my torque wrench. Aluminum is actually the material that fatigues. Carbon just breaks, as Kris mentioned, often catastrophically, but rarely when it's installed correctly (torque wrench is the best $75 I've spent on tools ever). Your Thomson seat post is designed to bend when it fails; not all alloy parts are.

Can you tell which of your commenters are at least as interested in bikes as they are in nature?

Lots of interesting info. I'll have to watch for bugs that raise their hind ends as I ride or walk past - evolution certainly can take unexpected paths.

ReplyDeleteLove the photo of the mice, particularly the one laughing/howling - made me laugh.

Happy Friday the 13th!

mtb w

Thanks for the post KK.

ReplyDeleteI think the problem with carbon is mainly with weight weenie carbon. I run full carbon DH bars which are probably twice the weight of the XC version and have zero worries.

Steel and Ti supposedly last forever, but they break too. Al often fails catastrophically as well. There is no guarantee of a bend.

Anyway, the moral is to inspect your stuff to try to catch it early. I understand that Carbon is a more difficult to evaluate and catch the small early warnings than the metal stuff.

I would love to see more manufacturers taking carbon from the ultra light weight category into the ultra strong and stiff regardless of weigh category. Ibis is a good example of this.

Personally, I would be terrified on a 16lb road bike or 20 lb mtb, but maybe I could learn to trust it eventually:)

Hey guys- so first off, look again- I installed a new CARBON bar. I love the feel of carbon bars on an mtb, have been riding them for ~10 years, wasn't switching back now. But my old bars had 7 years on them, thousands of miles and a couple dozen Gooseberry trips- I was getting spooked. KKris' post didn't really change my mind about carbon, but it did remind me of veteran bars, so I couldn't resist poking fun.

ReplyDeleteSBJ- Good to know you have a torque-wrench, and I'll hit you up next time. For this install I did my seat-of-pants torque-test: absolute minimum tightness under which controls/bars don't spin when I take a hit.

Enel- Lightweight road bikes aren't scary- not till about 50MPH anyway. Or when a Camry turns left without signaling. BTW, would love some more tarantula pics.

mtb w- Yes, Friday the 13th. You'd think after my recent luck I would've made it a bike-free day. Fortunately my (short) ride today was uneventful.

Your account of why you avoid Darkling Beetles struck a nerve with me today, Watcher. I, too, try to avoid them on the trail.

ReplyDeleteWhy kill something "out of laziness or convenience"?! But all those spared beetles probably don't make up for the mouse I killed today. He was in our house, and I caught him in a plastic food storage container with the intent of taking him several miles away to release him. I gave him air once, but then I went out for a few hours and when I came back he was upside-down dead. I killed him via neglect and I feel really bad.

Sorry about your finger and about the stalls in your life. Hope things turn around for you soon. Keep your butt, er, I mean chin up.

Jube- Ah, that sucks. Sorry for the bummer. And here you were trying to be all humane... Small consolation: my next post involves a small animal-capture story with a happy ending.

ReplyDelete