After a couple days camping and exploring along the Lochsa, we headed back over Lolo Pass into Missoula. As we rolled down into Montana, the Ponderosa forests seem strangely dry and open- we’d left the cedars, the hemlocks and all the other Columbian stuff on the other side. We ate dinner in town, and then spent the night, the last of our vacation, in a hotel.*

*Wyndham Inn, out by the airport. It has a pair of awesome (indoor) waterslides that are a huge hit with kids. Late that afternoon I kept an eye on the Trifecta while AW napped up in the room. I’m pretty sure Bird Whisperer went down in excess of 60 times.

Side Note: The Lolo Pass visitor’s center is well worth a stop. In addition to a great guidebook selection, the staff on-hand is both knowledgeable and helpful. I was fortunate to stop in while the wildflower expert was there (sadly I spaced her name) and she spent about 15 minutes poring over lame flower shots with me on my teensy camera screen, helping me to identify False Bugbane and Lovage, as well as answering a number of my questions about trees (specifically White Spruce and Grand Fir) in the area.

First White Flower

It’s also a host for some viral diseases affecting crops, the best example being PotatoYellow Dwarf Virus (genus = Nucleorrhabdovirus), which causes stunted growth, cracking and malformation in potatoes. Oxeye hosts the virus, which is transmitted to potatoes by a species of Leafhopper, Agallis constricta*, which feeds on the tissues both plants.

*Leafhoppers are Hemipterans, or True Bugs, which I explained in this post.

Despite all this nastiness, Oxeye Daisy is still regularly planted as an ornamental, used both in public works projects (lining highways) and as a popular garden planting. Yikes- watch what you plant!

Side Note: In fact closer to home right now, blooming Oxeye lines the lower reaches of the “Center Trail” in Pinebrook. The developments in Pinebrook and Jeremy Ranch are a stew of planted/escaped exotics.

*Although in fairness Engelmann Aster doesn’t seem anywhere near as tolerant of direct sun as Oxeye, so probably isn’t an easy yard planting.

Second White Flower

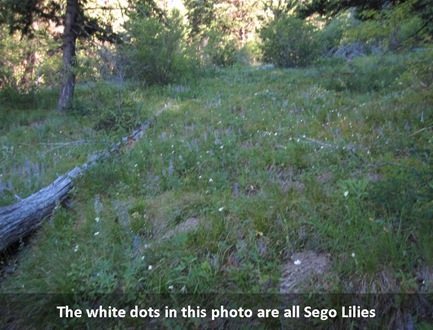

After a couple of miles, the trail veered away from the meadows and creek and climbed stiffly for a bit. Heads-down, trying not to spin out, I didn’t pay much attention to the surroundings for a minutes. When the grade eased up and I started to look around, again, I was in an open Lodgepole- Douglas Fir forest, and the white flowers lining the trails were something else- Sego Lilies, Calochortus nuttallii.

Third White Flower

The trail worked its way switchbacking up a long, mellow slope, and now and again the forest opened up and afforded me a view to the South, back down to the Missoula Valley far below.

Three Dozen Lakes

The Pacific Northwest is filled with evidence of the Lakes Missoula- scablands, gravel beds, bands of “rock flour”, and boulders hundreds of miles from where they

*I doubt it. There may be a slightly better (though still slim) chance an observer could have been around to see the downstream effects in say NW Oregon around 12KBP, but then an even less likely chance that they would’ve survived to tell the tale.

Fourth White Flower

Extra ID Detail: Confusingly, another Pedicularis species, P. racemosa, is also called Parrot’s-Beak. Both flowers are also called Lousewort, sometimes Sickletop or Leafy Lousewort in the case of P. racemosa, Coiled or White-Beaked Lousewort in the case of P. contorta. The flowers are similar; the giveaway here is the leaves. Pinnately-lobed into long, narrow segments, they mark it as P. contorta.

Pedicularis is a a member of the Broomrape family, Orobanchaceae, the same family as Castilleja, the Paintbrushes. Like the Paintbrushes, and in fact all species in the family*, Pedicularis species root parasites**, tapping into the roots of neighboring plants for nutrients.

*One exception- the genus Lindbergia. There’s always an exception in botany…

**Root parasites are different BTW than the myco-heterotrophs, such as Pinedrop and Coralroot, that we talked about in the last couple of posts. A myco-heterotroph taps into fungus (though that fungus may in turn tap into another plant.) A root parasite taps directly into the roots of another plant.

Parrot’s-Beak is a promiscuous parasite, not at all particular about the species of plant whose roots it taps into, and a single

Extra Detail: Queen Bumblebees usually forage for nectar, while workers usually go for pollen. The best way to get at the nectar is to enter the flower right-side-up*, while it’s easier to access pollen if you go in upside-down. So if you see Bumblebees around these flowers, their position as they enter the flowers may give you a clue as to whether they’re queens or workers.

*Technically, entering a flower right-side-up is do to so nototipically, while entering upside-down is sternotipic. I’m not clear why special science-words are necessary in this case; “right-side-up” and “upside-down” would seem to describe the behavior just fine.

Two Signs

Finally the trail started to level off. I rounded one more corner, and I was at the end, the wilderness boundary, with the standard wooden sign, and a special “Bicycles Not Permitted” about 10 feet beyond, just in case a biker somehow missed the first sign.

But I don’t. Not for any of the supposed reasons, not because I’m afraid of ticking off hikers*, nor because I’m afraid of getting caught**. I don’t ride in wilderness for the real reason, the reason that matters, the reason I can’t figure out why the pamphlets and signs don’t make clear: Bikes shrink distance.

*I could’ve easily popped in a couple of miles and back out before the day’s first hiker made it up to the boundary.

**Seriously, how often do you see an actual ranger on USFS land, actually walking on a trail?

The real problem with wilderness is that there isn’t enough of it, and that the pieces there are in the lower 48 are too small. They’re too small to support large predator/prey populations. They’re too small to let fire, blights, bark beetles and alien species invasions run their courses. We set wilderness up supposedly to protect the land, to protect wild species, but the truth is, we set it up for us. We take vacations and camp and hike and ski in it. We buy postcards and screensavers of it. Which is all sort of ironic, because the best thing for the wilderness itself would be if we didn’t go in it. Any of us. Not motorheads, not mtn bikers, not tree-hugging granola-head hikers.

That’ll never happen of course, and I’m selfish enough I wouldn’t make it happen if I could. So the compromise we work out is to make it a bit difficult, and more importantly, slow to penetrate wilderness. Walking is slow; it takes full day to cover a dozen+ miles on foot. But bikes are fast. In 2 or 3 hours a biker on a decent trail can penetrate 10 or 15 miles into a wilderness. And when anyone with a few hundred bucks can buy a mtn bike, throw it on the roof and drive to a trailhead, well, that’s a lot of people getting in deep and getting in fast.*

*A common objection here is that horses are permitted in wilderness. Horses don’t cover distance as quickly as mtn bikes. More importantly, horses are logistically impractical for the vast majority of visitors, which naturally limits their numbers and penetration.

Even so, being on smooth singletrack at wilderness sign with no one around is a little like finding a suitcase of money. If nobody knows, well then… I glanced at my watch and thought of the family waking in the hotel, shuffling down to the breakfast buffet. I could just go a little ways in, just to see what it looks like up ahead… maybe just 100 yards, or like a quarter mile or so…just for a few minutes…Catching myself, I turned around and started the long, fast descent down.

Fifth White Flower

Zipping downhill, I thought about the long drive home, and all the things I needed to do when I got there- work stuff, bike stuff, yard stuff. Down, down, down, through changing forests until at last I was speeding along the grassy meadows I’d started up at dawn, thinking about the yard stuff in particular, when all of a sudden I noticed one more white flower, one new and familiar at the same time, for it was the same flower blooming in my backyard just 2 weeks earlier, Mock-Orange, Phildelphus lewisii.

Philadelphus, a member of the Hydrangea family, Hydrangeaceae, is a genus of some 70 species of large shrubs scattered across the Northern hemisphere. Its hard-but-flexible wood was used by Indians to fashion baskets and other implements.

*These would be the homes of Mildly Grumpy Rich Old Guy and Space-Shot Babysitting Sisters. Both are actually fine neighbors, but the green wall is welcome just the same.

Note About Sources: Info on Pedicularis came from Phylogeny and the Evolution of Floral Diversity in Pedicularis (Orobanchaceae), Richard H. Ree. Info on Philadelphus came from the Master of Science, Plant Biology, thesis of Yuelong Guo, North Carolina State University. Info on Lake Missoula came from Glacial Lake Missoula and its Humungous Floods*, by David Alt.**.

*Yes, that’s really the name of the book.

**The same David Alt who authored Roadside Geology of Idaho. David Alt rocks.

Nice post! Full of good stuff. I like the tidbit about the worker bee/queen bee distinction. So, the queen gets to go in straight up while the worker has to go butt up - come on worker bees, unite! But I guess it's good to be the queen.

ReplyDeleteSometimes I resent bikers when I am hiking, but it's usually b/c I am jealous of how fast and fun they are traveling while I am going sooo slow (unless they buzz me - that's a different story).

And yes, the "real reason" for keeping mtbers out is due to the annoyance of hikers. When the USFS reviewed its ban on "mechanized travel" in the last couple of years and decided that such term included mtb bikes (even though clearly Congress meant no such thing), I think the only group raising a stink about mtbers were hikers.

mtb w

Great job, W, and a lot of (nonwilderness) ground covered. I like your take on why wilderness is w/o bikes, but agree with anon that it's nice there are a few nonbike places...

ReplyDeleteKeep up the good work, eh?