Back to the Triangle. The 3 vertex stars are Deneb in the Northeast corner, Vega in the Northwest, and Altair to the South. Vega appears the brightest to us, but it’s not so in absolute terms.

Like most constellations, the stars of the Triangle are nowhere near each other in space. Two of the stars, Altair and Vega, are fairly neighborly, at only 17 and 25 years distant from us respectively. But Deneb is a humongous ~1500+ light years away. With an apparent magnitude* of 1.8, it is the farthest first magnitude star in the sky.

*I explained apparent magnitude is the last post. Aw, it’s not that hard- go read it, already.

Tangent: For my lurking coworker readers*, if you think of constellations as Templates in the Reference Architecture, then the Summer Triangle would be analogous to the template map for a specific coverage area. Cool, eh?

*I am speaking here specifically to lurking coworkers at the formerly-independent-but-now-acquired-company**. If you are a lurking coworker of the new/acquiring company, you are not supposed to be reading this- I’m staying in the closet.

**And you- lurking coworkers at formerly-independent-but-now-acquired-company- are not out me to coworkers of the 2nd category. Trent, I am talking to you.

Explanation and Bonus Tangent for Non-Coworkers: So my company sells IT research services. Part of our product is this thing called the Reference Architecture, which is a framework of tools intended to help our clients figure out what to do with

*Seriously, I know that like 99% of the time, people telling you about their jobs is a total yawner. Really, unless you’re an astronaut, movie star or a hit man, who cares? I’ve only met 2 people my entire adult life whose jobs I really wanted to hear about**. I hate it when people ask me what I do at parties. I want to be nice, but what I really long to say is, “Listen- unless you work in IT you won’t get what I do, which means that I’ll go through a long and painstaking explanation of what I sell and why companies buy it, which will be tiresome for me and boring for you. All you need to know is that I make a living, it’s legal, and it pays the bills. Now let’s talk about something else.”

**The first is an honest-to-god sex researcher. I see him about once a year at the holiday get-together of a mutual friend and always make sure to sit next to him, because he’s always working on something fascinating. The other was a former FBI agent who did a long-term deep cover assignment in organized crime. The most remarkable thing he told me was that the vast majority of mobsters were really, really nice guys, people you’d want to have as friends in real life.

There’s a third component to the Reference Architecture called Principles, which are statements about the specific client organization, and its context, requirements and environment related to technology decisions. (For example, is the company a single-vendor shop, or do they follow a best-of-breed approach.) The Principles are almost like the “Technology Ethic” of the client organization.

One of the ideas I’ve had for a while is to use this same model for a self-help book: The Life Reference Architecture. There’d be Decision Points about things like education, career, romance, marriage, child-rearing,

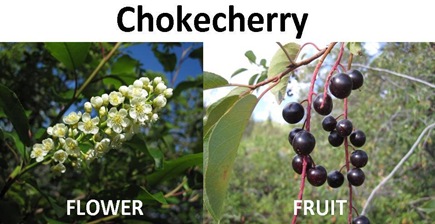

*Botanist. Hello. Have you even been reading this blog?

**No.

***Yes.

****Then I would go around the country, giving engaging, high-priced seminars, and making appearances on Oprah and such. I would be like Dr. Phil, except that that my methodology would be process-based, I wouldn’t have a folksy Southern drawl and I would have great hair, like Rafinha Bastos. This thing has Cash Cow written all over it and is far and away my Best Idea Ever.

First Star

So anyway, the Triangle isn’t a constellation, but a helpful map of constellations. The first is Cygnus, the Swan, of which Deneb is the alpha star. Deneb is awesome, a blue-white supergiant some ~1,500+ light years away from us, that is almost unbelievably bright.

How bright? Deneb is the 19th-brightest star in the sky. There are probably in excess of 50 million stars closer to us*, of which Deneb outshines all but 18. The farthest of those 18- Rigel (#6, and which we looked at when we checked out Orion)- is only about half as distant. If you suddenly swapped out our sun for Deneb, it would shine in the sky ~160,000 times as brightly.

*Rough number I came up with by taking the estimated number of stars within 250 light years, assuming similar stellar density out to 1,500 light years, and remembering enough geometry to calculate the volume of a sphere.

*I found conflicting figures on this. Wikipedia says as far out as Earth’s orbit. Jim Kaler says only half that. Whatever- pretty freaking big, in any case.

Extra Detail: Deneb might be the brightest- in absolute terms- individual star you can see with the unaided eye. The other contender is Rigel, in Orion. I’ve found conflicting figures for magnitude and distance for both.

Deneb is the “tail” star of the swan. A somewhat more intuitive way to see the constellation is as a cross, or a kite, right-side up when you are facing South. Cygnus lies smack in the galactic disk of the Milky Way, and is filled with cool stuff, including star clusters*, nebulae** and interstellar clouds. Most of this stuff you won’t be able to pick out easily with binoculars; the background is so busy with stars that it’s tough to make out the clusters, and the nebulae are hard to see even with a small telescope.

*Including open cluster M29, just barely Southeast of Sadr. We’ve looked at 2 open clusters before- the Hyades and Pleiades- before. M29 is several thousand light-years further away.

**These include the Veil Nebula, just Southeast of Epsilon Cygni, which is thought to be the remnant of a Supernova between 5,000 and 8,000 years ago, as well as the North America Nebula (so named for its shape) which lies just a titch East of Deneb. The NA Nebula is an emission nebula, a cloud of gas ionized by the energy of a nearby star, which in this case may (or may not) be Deneb.

![MWay[4] MWay[4]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjLJLS2PdObGGPN79fJOErPiQMwxkazGh3vjF6AAw9lB-crX5ZVpYwNllJ1KKZulOH3KyYPiGSyvgnjP7ck5vATPK40yZdeUlRJT4tOuSlG2BqB5IyVdIzTuzzdnPJuv1jgr7OFLFgfA4U/?imgmax=800)

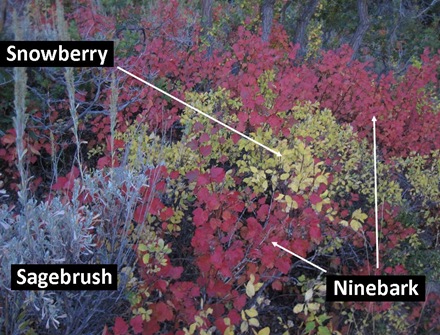

Extra Detail: Sadr, the central “cross-roads” star of the constellation, is partially obscured by dust, and would appear twice as bright if it were not. Through binoculars a small unnaturally dark patch seems to surround the star. BTW, you won’t see these dark/cloud patches I’m describing from an urban area. If you live in Salt Lake Valley drive up to Little or Big Mountain Passes on a moonless night (like now).

Second Star

Vega appears as the brightest vertex of the Triangle, and the 5th brightest star at in the sky. When astronomers first measured the radius of Vega, they found that the star appeared to be significantly bigger than their models predicted. The reason turned out to be that Vega is spinning so fast that its shape is actually distorted, making it “fat” around the waist. Vega is about 25% “wider” at the equator than it is “tall” at the poles.

Pretty much every celestial body rotates. The Earth spins at a little under ½ a kilometer/second. The sun spins a bit faster, at around 2 km/second, completing a full rotation about every 3 ½ weeks. Vega rotates at over 270 km/second, completely rotating roughly twice a day. If it were to spin just a little faster- 290km/second or so- it would start to fly apart.

Vega will be an important star in future. In about 11,700 years it will be the effective North Star, as it last was 14,000 years ago, due to the ~26,000 year-long cyclic wobble of the Earth’s axis known as the Precession of the Equinoxes*. Vega is working its way closer to us, and in about 290,000 years will become the brightest star in the night sky. It’s not moving alone; the star belongs to a group of stars headed in the same direction known as the Castor Moving Group, which also includes (of course) Castor in Gemini, Fomalhaut in Piscis Austrinis and Aldemarin in Cepheus.

*Which I explained in this post.

Extra Detail: We looked at Castor in detail in this post; it’s now visible in the morning. Fomalhaut*/Piscis Austrinis is way South and not often visible from here, but you can make it out in early evening right now way low in the sky if you have an unobstructed Southern view. Cepheus we haven’t looked at, but is easily visible now in the early evening, North of Cygnus and sort of in between it and Cassopeia.

*I have a soft spot for Fomalhaut; it was the home star of Ursula K. LeGuin’s Rocannon’s World.

Like the sun, it’s a main-sequence hydrogen-fuser about ½-way through its lifecycle. But that life will be much shorter than our sun’s; Vega is only around 400 million years old- remember, big stars burn faster. Given its location and aspect, we should be glad Vega isn’t larger. It lacks sufficient mass to go supernova. With its pole pointed straight at us, we’d receive the brunt of the gamma ray burst, which at that close distance*…

*A nearby supernova is one of the suspects in the Silurian extinction, as I described in this post. Man, it is like I have a post for everything.

Epsilon Lyrae is a true double that can easily be discerned with binoculars, and maybe, just maybe with the naked eye. It’s like Mizar and Alcor in the Big Dipper, but tougher. (Bird Whisperer claims to see both components naked-eye.) Each of these 2 stars is in turn double, and then one of these 4 stars is double yet again!

Third Star

Altair, the Southern vertex of the Triangle, is the alpha star of Aquila, the Eagle (which is basically a sideways diamond with a tail). Altair is the 13th brightest star in the sky, but that’s only because it’s so close, at 16.8 light years. Like Vega, it’s a rapid and distorted spinner, rotating at a frenetic 210 km/second, and with- like Vega- a 25% greater equatorial than polar radius. The star rotates completely every 10 hours.

*Or the main body of the “teapot”, which is a bit easier to make out than a centaur drawing a bow. In any case, I just look for the “wedge”. Sagittarius is a cool constellation and I’m sorry to short-change it just for a quickie skymark, but I likely won’t get a chance to post about it before it disappears from the Southern sky until next year.

![East8PM[4] East8PM[4]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgS5h_-mv864nwq1N_3fA9_3V9vtT7ECXcE_Ki4TlXax6kBztggCSo5cL68SE-B23CUruUSVQMppGIIh9oForatm6ydKkJ040hj-VIYFaLMOOAbO8IHW-HIwZ_btzEgkCQGwFwgFZjg924/?imgmax=800)

Note about Sources: Many of the same sources as for the last post, specifically Jim Kaler’s STARS site, Atlas Of The Universe and StarrySkies.com, as well as Starsurfin.com and the Daily Kos. Additional info from Wikipedia. BTW, didn’t the book cover turn out awesome?