After my ride I showered, dressed and drove into the office. At about noontime I walked out the back door of our building, by the

Tangent: Right by the back door of my office building is, as I mentioned, a little overhang with a bench where smokers hang out. Two of my coworkers- let’s call them “Aaron” and “Jimmy”*- are smokers, and I’ll frequently stop to say hi to one or the other on my way in or out of the building. Sometimes they’ll be chatting with other smokers, and other times just taking a break alone, quietly looking out across the creek, or toward the mountains in the background. And, I have to admit that deep down, I am a teeny bit envious. Smoking gives them an excuse to go outside, sit on a bench on a nice day and, for a few minutes, do nothing. Oh, I get that smokers also have to huddle outside on freezing days, but here in Utah it seems that there are, on the balance, more nice than bad days to pass a few minutes out-of-doors.

*Not to be confused with “Fast Jimmy”, who does not smoke, and is not a coworker.

Of course we non-smokers can also take mini-breaks, but since we don’t have an “excuse”, we’re more furtive about them, and spend them staring at our screens, pretending to work, while we read blogs or Dear Prudence* or whatever.

*I always thought I’d make a great advice columnist. How do I get that job?

Office smokers also tap into a little social network that we non-smokers are largely cut off from. There are probably a dozen other companies represented in our building; I don’t know a soul from any of them*. But Jimmy and Aaron are often chatting easily with smokers from several other companies, and so, oddly, smoking has expanded their world.

*Except that crazy older woman with the spiky red hair who always tries to start up a conversation with me in the elevator. Or did, anyway. Now I always take the stairs.

Nested Tangent: It’s probably expanded the world of Aaron- who is single- even more, as several of the smokers over the years have been attractive young women. For a while I teased Aaron about this, as I often came across him smoking/chatting with 2 particularly striking young women who worked at the multi-level-marketing company downstairs*, and whom I referred to- in what I always felt was a particularly inspired bit of double-entendre- as “the Smoking Hotties.”

*Special Footnote for Non-Utah Readers: Every office building in Utah contains a multi-level marketing company. The products touted are almost always health/wellness-related, which is kind of ironic in that most of the people who actually work at these companies, uh, don’t look all that healthy.

Yes, I know that Aaron and Jimmy will likely pay for their pleasant downtime-breaks and expanded social world by, well, you know, dying horrible premature deaths and what-not, but that’s not the point. The point is- and I do have one- why do you need an excuse to go hang outside for 5 minutes in the middle of the day? If I just went out and sat on the bench and a coworker passed and saw me doing nothing, they’d probably think it a bit odd. But if I were smoking, well then that would be totally fine…

The order Odonata, which includes both dragonflies and damselflies, includes some 5,500 species across all continents except Antarctica. The big obvious difference between dragon and damselflies BTW is the resting position of the wings. If it folds them back when at rest, it’s a damselfly; if it keeps them out at 90 degrees to the body, it’s a dragonfly.

Extra Detail #1: They also exhibit different mating flight patterns. Dragonflies generally mate while flying. Damselflies spend more of their mating time perched, but often fly- while connected- for short distances from perch to perch.

Tangent: Every once in a while, you’ll see or hear about an animal doing something that looks really fun- jumping out of the water, swinging between tree limbs, flying rapidly through the air. I just want to point out that mating while flying sounds like about the funnest thing imaginable.

Extra Detail #2: Odonata appears to be monophyletic, meaning the group includes all of the descendants form a common ancestor. Dragonflies (infraorder Anisoptera) also appear to monophyletic. But damselflies (Infraorder Zygoptera) appear to be paraphyletic, in that one big genus (Lestes) turns out to be more closely-related to dragonflies than to any other damselflies.

*I explained monophyly and paraphyly in this post.

The dragonfly I rescued is one of the most common species in North America, and if you’ve ever paid attention to Dragonflies you’ve almost certainly noticed it. It’s the Common Green Darner, Anax Junius, and its distinctive green color is a quick identifier, as is the apparent “bulls-eye” atop it’s forehead/“nose” when viewed from above.

If you know anything about dragonflies, you probably have heard that they develop through an aquatic “nymph” stage (pic right, not mine)

But an adult darner lives only for a couple of months. Think about how weird this is. We think of animals developing like mammals and birds and reptiles generally do- we’re born, we grow up quickly, and spend the majority of our lives in sexually mature adult form. But what if you were born, grew to about the size of an 8 or 9 year old, and then stayed that way for like 60 years? Then, right around when you collected your first social security check, you suddenly hit puberty, grew armpit hair and got interested in the opposite sex. But you had to hustle, because you only had a few years or so to marry and have kids before you dropped dead! That’s pretty much what the lifecycle of dragonflies (and many other insects) is like…

A dragonfly’s life, therefore, is mainly a nymph’s life, which most of us never see. Dragonfly nymphs are fearsome aquatic predators. How fearsome? Did you ever see any of the Alien Movies?*

*I love the original Alien. The various sequels never worked for me. But I loved the original. I’ve seen it like 10 times, and every time where it gets to the part where Sigourney Weaver goes back for that cat, I’m always yelling at the TV, “Screw the cat! Just get out of there!”

The super-scary alien-predator in the Alien movies had several fearsome weapons- spiked tail,

*I explained emergent plants in this post. Man, it is like I have a post for everything.

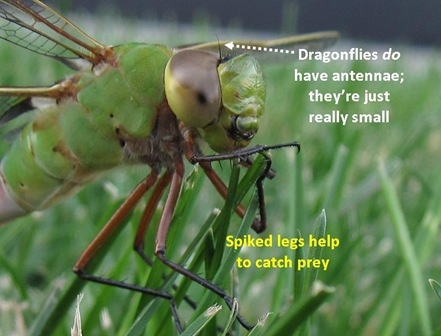

As aerial predators, dragonflies feed upon all sorts of mosquitoes, midges, gnats, flies and other insects. Their 6 spiked legs, held in a basket-like formation as they fly, are used to scoop up prey toward the mouth.

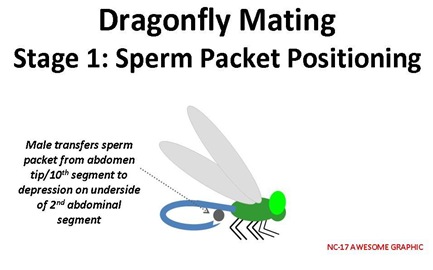

Male Green Darners, like most male dragonflies, are territorial, and patrol their territory getting into tussles with interlopers, and looking for females. The male produces a sperm packet from the tip/10th segment of his abdomen, and then curls his abdomen under itself to deposit the packet in a small depression on the underside of his 2nd abdominal segment.

Extra Detail: Dragonflies use the same XX/X0 chromosomal system of sex determination used by Fruit Flies, which I described in last year’s Housefly series*. I had a hell of a time BTW determining the chromosome # of A. junius. I believe the diploid # is 27 (male)/28 (female) but this could be wrong.

*Man, was that an awesome series or what?

Damselflies, BTW, remain connected for egg-laying, but take it a step further. The pair lands on an emergent plant stem, then crawls down together- still connected- beneath the water’s surface where the female deposits the eggs into the stem of the plant. It’s suspected that the pair may do this together because the female requires the added strength/mass of the male to break the surface tension of the water and re-emerge into the air.

One of the reasons dragonflies fascinate me is that, like sharks or scorpions, it’s a really old design that’s held up amazingly well. Think about it.

![Apposition Graphic[4] Apposition Graphic[4]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiThO2giKKQgtQrRnUz_r5Ly4Y8HFnP92lsNNgzOp_KRYUQneNFxfUVqy_MHl9EkKwTjASQj5o9ZHV3RoFPe6B2UbA6r6pmbty3ZY4YOw7uQlgMkI2rwDpsDEmYdTYrdrmG-y9TWS__Uj4/?imgmax=800)

![Dragonfly Field Vision[5] Dragonfly Field Vision[5]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjcsc4u2ilz4bH0UXKQFTMQ1YzVrt27uCzctH5f1JCPIAqTmzvlx-3JIdET8uCbPqxt5ANKi90KC8ykflMgRf00TEjXauwDmSdMfgWGnyj0KehypM1wvDapyklLmC3RUE-TjzWCutk6RPM/?imgmax=800)

Side Note: I should mention that the whole topic of the evolution of wings and flight in insects is one of the big stumpers in evolution. There are lots of ideas, but still no consensus. With something like a bird or a bat or a pterosaur, even if we can’t figure out exactly how it evolved flight, it’s pretty obvious where the wings came from- the forelimbs. But there’s not an equally obvious wing-precursor-limb in insects. One thing that does seem apparent is that insects don’t seem to have been particularly successful or abundant before evolving flight…

Yet dragonflies are awesome fliers. They’re fast and maneuverable, rapidly changing direction and accelerating on a dime to speeds of >60MPH. They can also fly backwards (though at only around 3% their maximum forward speed), and hover in place for up to a minute.

Extra Detail: Know why they can’t hover longer? Because they overheat, which makes perfect sense when you think about it. Dragonflies do most of their flying at significant speeds, experiencing fast, cooling airflow. In the absence of that airflow, they run hot. Plus, their tracheal respiratory system- to which we will return momentarily- is more efficient in strong airflow.

Dragonfly wings, though ancient in form, turn out to be remarkably sophisticated. They consist of largely clear membranes held in place by a network of veins. All dragonfly and damselfly wings have 5 primary veins. Some veins are darker and thicker than others, and these support portions of the wing that experience greater stress during flight. The wing has a notch/vein-junction on the forward edge called the nodus, that is critical to the strength and structural stability of the wing.

*Only do this with an already-dead dragonfly. Man-handling the wings of a live dragonfly will likely mean its early demise.

**I should say “consistent curvature”. It could be argued that the wings exhibit a type of cumulative effective curvature. See sources for more details.

Side Note: While we’re on the topic of wings, it’s worth noting that these structures and characteristics

The presumed reason for large size was the greater concentration of oxygen in the atmosphere in the Carboniferous, likely over 30%*. The increased O2 levels would have made the tracheal respiratory system of insects** more efficient, allowing them to grow- and fly- at much larger mass.

*Which is higher than the concentration necessary for wet wood to burn, and makes you wonder about the forest fires in those times…

**Which I touched upon in this post.

What’s interesting about oxygen and bugs in the Carboniferous though is that although many other bugs grew much larger than they did today, not all of them did. Cockroaches for example, which also were around at that time, did not grow particularly large. In fact, I believe(?) that the largest cockroaches that have ever lived are around today. In recent experiments researchers have raised dragonflies*, roaches and other bugs under hyperoxic (high oxygen level) conditions, and found that while dragonflies, and most other insects, grew bigger and faster than they do at normal O2 levels, the roaches grew at roughly half the rate the do otherwise, and their tracheal tubes were abnormally small.

*Dragonflies are apparently a real bitch to raise in captivity. Feeding them is the problematic part…

So what was my lady dragonfly doing just laying around on the sidewalk? Maybe she was old and about to check out. Maybe she was out hunting and nightfall caught her out and about. Or maybe, just maybe, she’d spent the night in unfamiliar country, in the middle of a migration.

In the Eastern and central US, Green Darners are known to form huge swarms, numbering up to over a million, migrating South in the Fall. Their paths and destinations are not completely known, but swarms have also been reported in Central America, suggesting crossings of the Gulf of Mexico. Such crossings, if they do occur, are certainly possible. Although the maximum fat-reserve slight time of a Green Darner is thought to be only about 8 ½ hours, migrating dragonflies often feed while on long-distance journey, taking sustenance from what is known as “aerial plankton”, including tiny aphids, midges and spiderlings aloft in the sky.

Extra Detail: The ~8 hour estimate comes from analysis of dragonfly body fat, which can account for up to 30% of body mass. Whoda thunk?

Dragonfly migration, like that of monarch butterflies, is multi-generational; the dragonflies who fly South in the Fall are not the same individuals who fly North in the Spring. Long-distance migration is always awesomely impressive, but multi-generational long-distance migration even more so. How on Earth do they do it? Does every dragonfly have a built in instinctive geographic map and awareness of the world? Do they crawl up out of the swamp, do a final molt, and think, “Oh hey, looks like I’m in Belize. Guess I better start flying to Ontario…”? That’s hard to swallow. Insect brains are teeny-weeny-tiny, and in dragonflies, something like 80% of that teeny brain is believed to be devoted to visual processing. It seems unlikely that they could possess anywhere near that level of geographic self-awareness,

To try and better understand dragonfly migration, researchers in the Fall of 2005 captured 14 Green Darners (1/2 male, ½ female), equipped them radio transmitters, and then monitored their positions for an average of 6 days each. What they found was that migratory flight appeared to follow simple, predictable rules. For example, the dragonflies migrated Southward roughly every 3 days. A Southward-flying day always occurred when the previous night was colder than the night before. Migration days tended to occur on days with lower windspeeds, and no dragonfly was observed migrating on any day where the winds gusted to over 16 mph. Winds were most often Northerly on migration days. Many of these behaviors are remarkably similar to migrating songbirds, who regularly mix up migrating and “stop-over” days over the course of their annual migrations.

In other words, the behavior suggested that a dragonfly brain follows simple, almost Boolean, rules in migration and navigation, which might explain how something so small-brained might accomplish such impressive long-distance navigation and migration.

Tangent: There’s a wonderful analogy here that I can’t resist. Remember the Life Reference Architecture tangent from the Triangle Man post? It’s like the Dragonfly brain contains a “Migration Decision Point”, a set of Boolean, context-driven rules, which guide its decisions in that part of its life. I wouldn’t be surprised if dragonfly behaviors in other areas- hunting, mating, predator-evasion- could be similarly encapsulated in Boolean format. Maybe the Reference Architecture is an effective analogy for how an insect brain works- a set of Decision Points that, in simple form, drive apparently complex context-based decisions.

Green Darners don’t always migrate in swarms (and to my knowledge swarms don’t occur in the Western US). Sometimes they migrate solo, though again, it’s not clear how far or where. But fascinatingly, many Green Darners don’t migrate. Instead they over-winter, and do so in really cold places all over the US and Southern Canada. They over-winter not as adults, but as nymphs, in sort of a diapause, or delayed developmental state, under the ice in frozen ponds, wetlands, etc.

So if Green Darners can over-winter in cold climes, why migrate?

Side Note: This kind of lineage-analysis has been done with lots of creatures, including humans. You’ve probably heard of the “Mitochondrial Eve”, the presumed most recent common female ancestor of all people alive today. Subsequent research has suggested all sorts of more recent maternal and paternal lineages all over the world. A fascinating example is described in Brian Sykes’ Seven Daughters of Eve*, which details research around the seven maternal lines from which the vast majority of Europeans appear to be descended within the last ~55,000 years or so.

*The concept and research of the book is fascinating. The fictional what-if chapters were a little less compelling for me.

What researchers found was that both migrants and non-migrants existed in multiple separate Green Darner lineages, meaning that non-migratory (and/or migratory) behaviors had apparently come about repeatedly and independently, suggesting a significant degree of “plasticity” in migratory tendencies across the species.

By now you’re probably getting an idea of why I characterized Green Darner migration as confusing. I don’t know where my lady dragonfly came from, or how she wound up on the walkway by the smoker’s hang-out. But I’m glad I stopped to check her out. Second bug rescued.

Note About Sources: I had awesome sources for this one. Thanks to friend and fellow nature-blogger KB for her help in accessing materials. General info on dragonflies came from National Wildlife Federation Field Guide to Insects and Spiders of North America, the Insects of West Virgina website, Suite101.com, and the Tree of Life web project. Info on dragonfly wings and aerodynamic properties came from Aerodynamic Characteristics of Dragonfly Wing Sections Compared with Technical Aerofoils, Antonia B. Kesel. Info on Green Darner migration swarms, behavior and genetics came from Simple rules guide dragonfly migration, Martin Wikelski et al, Massive Swarm Migrations of Dragonflies (Odonata) in Eastern North America, Robert Russell et al, Genetic diversity and widespread haplotypes in a migratory dragonfly, the common green darner Anax Junius, Joanna R. Freeland et al and Phylogeny of the Dragonfly and Damselfly Order Odonata as Inferred by Mitchondrial 12S Ribosomal RNA Sqeuences, Corrie Saux et al. Additional swarming info came from The Dragonfly Woman, the blog of entomologist Christine Goforth, which I recommend for anyone interested in dragonflies.

Remember kids: "Smoking hotties" become prematurely wrinkled hotties with voices a la Patty and Selma Bouvier. You've been warned.

ReplyDeleteMLM companies: So I can blame Utah for this? Just last week, a former classmate asked me to talk to a "friend" of his about the friend's business idea. I said sure. Turns out it was an hour-long pitch for a MLM "wellness" company... although in fairness it was out of Idaho, not Utah.

Dragonflies hitting puberty in their relative 60's seems extreme, but mayflies take it a step further. Mayflies spend most of their life in nymph stage, emerging from the water just long enough to mate and, for the females, lay eggs. Then they die. They emerge with no mouths, as they do not feed during the adult stage--it lasts a matter of hours. Hope the flying sex is really, really good, because they're not getting much of it.

ReplyDeleteBut damselflies (Infraorder Zygoptera) appear to be paraphyletic, in that one big genus (Lestes) turns out to be more closely-related to dragonflies than to any other damselflies.

ReplyDeleteBybee et al. (2008) re-examined this using a much larger data set than the Saux et al. study and recovered a monophyletic Zygoptera. The idea of a paraphyletic Zygoptera seems to have been the result of inadequate sampling.

it means that “Damselfly-ness”, specifically the hinged-wing mechanism, has to have evolved at least twice among the odonates

Damselfly wings aren't hinged. Damselflies can't actually fold their wings 'back' any more than a dragonfly can; like a dragonfly, their wings only move up and down (though they do move over a much greater arc than dragonfly wings). Instead, damselflies have developed a majorly angled back, so that the part with the wings has become almost vertical instead of horizontal, so 'up and down' for the wings has nearly become 'forwards and backwards'. Compare this to most other insects that are able to rotate the whole wing rearwards flat over the back.

Offhand, Epiophlebia, the only living odonate that is not either a dragonfly or a damselfly, moves its wings in a damselfly-like arc despite being otherwise more like a dragonfly. So the ability to move the wings damselfly-wise is the ancestral condition for odonates; the specialised condition is the dragonfly arrangment of having them permanently outwards.

Phil- I'm pretty sure Patty or Selma (not sure which one) used to work at our office until about a year or so ago. (Lurking coworker readers know exactly who I'm talking about.)

ReplyDeleteSBJ- Yes, mayflies do take it to the extreme. Maybe having 2 penises helps them get the most out of their fleeting adulthood.

Christopher- Thanks for the update and pointer to the Bybee paper, as well as as the damselfly wing explanation. I'll check them (damselflies) out more closely next opportunity (which I fear may be next spring now).

Whoa, who knew dragonflies were so cool. No wonder that dragonfly decor motif was so popular a few years back.

ReplyDeleteI would go outside and just enjoy the day for a 5 minute break like the smokers do, but the smokers have laid claim to all the good benches around my office. Isn't that always the case?

Flying Dragonflies fascinate me. Something about there flight makes me often stop and watch. They are amazing creatures, and more amazing to me after reading this post.

ReplyDeleteBTW, the bulls-eye mark in the Green Darner Features photo sure looks like a Watcher eye to me. Coincidence? I think not.