When I started this blog, I wrote a “Point of the blog” type post, where I set out what I was hoping to do. The description- a middle-aged working dad who wanted to start paying attention to the natural world around him- was technically correct. But it was incomplete.

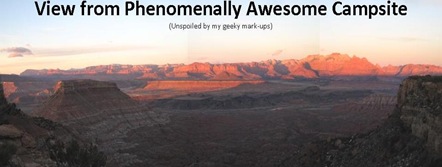

Three years ago this month, I took a solo “hooky” day to drive down to Southwest Utah and spend a day mountain biking in my Favorite Place In The World. I left straight from work, drove down in the dark to my Favorite Campsite In The World, rolled out my bag on the ground, climbed in and stared up at the night sky. I didn’t know much about stars back then, but had it in my head that I’d try to find a new constellation. I looked at the star-finder by flashlight, and decided to try and find Perseus.

I’ve regularly done solo trips for many years, but I had something on my mind on this one. For the past several months I’d been dealing with a sort of career-goals-life-direction, maybe mid-lifey, quasi-“crisis”, and was hoping to sort things out in my head, away from work, family, friends or other distractions for a day and a night.

![Perseus Andromeda Action Graphic[4] Perseus Andromeda Action Graphic[4]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgsMFqOjVG1NMAOartJ4I5yXiiKZUjtPwgRf-sfkjrB2SZxoQkgtJKYzsku4qQ2Ojyy676FlVSZmN9_kGfkMlOHURWvDI31NSDmA98QldGniPqXbuAchiybZHqv1hG0ekjTFFxCUliG_IY/?imgmax=800) Perseus, like most constellations, looks absolutely nothing like its namesake, who- as we already know from my previous post on Andromeda—was a semi-divine hero who made a living killing monsters, rescuing naked ladies chained to rocks, and flying around with a head in a bag. But what it mainly looks like is a wedge.

Perseus, like most constellations, looks absolutely nothing like its namesake, who- as we already know from my previous post on Andromeda—was a semi-divine hero who made a living killing monsters, rescuing naked ladies chained to rocks, and flying around with a head in a bag. But what it mainly looks like is a wedge.

Tangent: It took me a couple years of semi-serious stargazing to figure this out: most constellations look like wedges. Andromeda? Wedge. Cepheus? Wedge. Capricornus? Libra? Sagittarius? Wedge. Wedge. Wedge. This is probably because a wedge is basically a lopsided triangle, which one can readily construct with any 3 points in the same general vicinity. Anyway, the key to recognizing these constellations is to see the wedge, because all of the wedges are different, and, with a little attention up-front, easily recognizable.

The Life Quasi Crisis (LQC) had several different aspects, most of which aren’t things I’ll get into here. But the core of it was that over that last decade, I’d gradually come to realize where my real passion and interests lay, while at the same time, it seemed less likely that my career aspirations were likely to ever come to fruition.

The Wedge of Perseus consists of 4 main stars, which might make you think it looks quadrilateral-ish, but really it looks more wedgy, because 2 of the 4 are quite close together. The wedge points roughly North, and lies West of Auriga and East and a bit South of Cassiopeia*. As you lie facing South, scan West/Right of Auriga for the next bunch of bright stars. If you reach Cassiopeia, back up to the East/Left. The Southwest “base” of the wedge is Epsilon Persei.

*To find Cassiopeia, see this post. To locate Auriga, see this post.

Epsilon Persei, a double star, lies some 540 light years away. It’s a young, hot star, probably only about 10 million years old, which will go supernova* in only a couple million more. The bigger of the 2 shines 25,000 times as brightly as our sun, and more brightly than any other star in the constellation. It shines 5 times as brightly, and is just about the same distance from us, as Mirfak, the apparent brightest star in Perseus (and which we’ll get to momentarily) but appears dimmer as it’s partially obscured by clouds of interstellar dust.

Epsilon Persei, a double star, lies some 540 light years away. It’s a young, hot star, probably only about 10 million years old, which will go supernova* in only a couple million more. The bigger of the 2 shines 25,000 times as brightly as our sun, and more brightly than any other star in the constellation. It shines 5 times as brightly, and is just about the same distance from us, as Mirfak, the apparent brightest star in Perseus (and which we’ll get to momentarily) but appears dimmer as it’s partially obscured by clouds of interstellar dust.

*I explained supernovas in this post.

Extra Detail: I’m unclear whether these clouds are considered part of the Perseus Molecular Cloud, which spans about 6 degrees of sky a bit further South, centered around Zeta Persei*, roughly 600 light-years distant. This cloud lies within the Orion Spur- which is our “home” spur of the Milky Way- but further outward from the galactic core than us. In fact, everything we’re looking at in this post is away from the galactic center, and we know this because Auriga is our reference constellation for the Galactic Anti-Center.**

Extra Detail: I’m unclear whether these clouds are considered part of the Perseus Molecular Cloud, which spans about 6 degrees of sky a bit further South, centered around Zeta Persei*, roughly 600 light-years distant. This cloud lies within the Orion Spur- which is our “home” spur of the Milky Way- but further outward from the galactic core than us. In fact, everything we’re looking at in this post is away from the galactic center, and we know this because Auriga is our reference constellation for the Galactic Anti-Center.**

*Zeta, not shown on my graphic, lies South of the wedge and is the “foot” of Perseus. Go South from Epsilon about the same apparent distance as from Epsilon to Delta Persei, and it’s the next bright star you run into. The star is an monster, shining- in absolute terms- 4 times as bright as Epsilon, but it’s way, way farther away- almost 1,000 light-years.

**I explained the large-scale structure of the Milky Way galaxy in this post. I explained the Galactic Anti-Center in this post.

The passion/interest thing is probably pretty obvious- it’s a lot of the stuff in this blog, except that back then it was sort of an amorphous, loosey-goosey subset of the stuff in it. I was interested in trees and stars and open spaces, but didn’t know enough to be interested in things like birds or bugs or rocks. But I realized that the natural world was the real show going on, something that hadn’t really occurred to me way back when I was making early life decisions about things like education and career.

A

From Epsilon Persei, I scanned North and West for the next bright star, Delta Persei. The apparent span between Epsilon and Delta Persei is roughly on the same scale as one of the longer 2 sides of the Auriga pentagon, so I scanned about that distance till I found it. I’d made the first connection.

Delta Persei lies roughly the same distance- 530 light-years away- and shines more than 3,000 times as brightly as the sun. It’s about 6.5 times the mass of the sun, only 50 million years old, has just about exhausted the hydrogen in its core and is in the process of turning into a red giant. Delta Persei appears (not certain) to be a double, but its companion, roughly the size of the sun, is way far out- about 16,000 times the distance between the Sun and the Earth (or 165 times the max distance between the Sun and Eris). At that distance the stars would orbit each other about once every ¾ of a million years. If this sun-sized companion had a planet, Delta Persei (the main star) would appear as an incredibly bright star in the night sky, about 5 times as bright as a full moon, and easily visible even by day.

Delta Persei lies roughly the same distance- 530 light-years away- and shines more than 3,000 times as brightly as the sun. It’s about 6.5 times the mass of the sun, only 50 million years old, has just about exhausted the hydrogen in its core and is in the process of turning into a red giant. Delta Persei appears (not certain) to be a double, but its companion, roughly the size of the sun, is way far out- about 16,000 times the distance between the Sun and the Earth (or 165 times the max distance between the Sun and Eris). At that distance the stars would orbit each other about once every ¾ of a million years. If this sun-sized companion had a planet, Delta Persei (the main star) would appear as an incredibly bright star in the night sky, about 5 times as bright as a full moon, and easily visible even by day.

My “career aspirations” were, uh… to make money. That’s pretty much it. OK that’s a little general. Specifically- and this is an important distinction*- it was to make enough money that I didn’t have to work anymore.

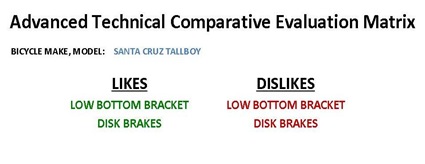

*Because I’m not really into having expensive stuff or anything. I drive an 11 year-old car, and buy a new mountain bike once every 5-7 years. It’s the security and freedom of money that I love. The security to never be losing my home or begging friends or family for hand-outs, and the freedom to (at least know that I could) walk away from any job, any time.

All About Money, Part 1

Tangent: One of the things in our culture about work and money that kind of irks me is how we all put on this sort of overdone show about career development and job satisfaction and meaning in our work and what-not, when the fact of that matter is that for the vast majority of us the #1 over-riding reason why we all go to work every day is to get money. And there’s absolutely nothing wrong with that. We’re trying to stay alive- buy food, shelter and a few luxuries- and money is the most practical way to do that. But there’s this thing about not acting like you do it for money. What’s up with that? I’m screaming loud and clear right now for the world* to hear: I worked for money!

*“World” in this instance would consist of the ~couple hundred people per day who visit this blog, approximately 50% of whom are searching for Salma Hayek photos.

In my family/culture (upper middle-class* Northeast US) the expectation was that you go to college following high school graduation, which like it or not, necessitates at least some preliminary decisions about career path. But I had no idea at age 18 what I wanted to do, other than I didn’t want to go to school for any longer than I had to, and didn’t want to be dependent on my parents for money. So I majored in (electrical) engineering, because you could get a decent-paying job with a bachelor’s degree.

*I’m not really sure what this means. Practically everyone in the Northeast US says they’re “upper middle-class”, don’t they? Unless they grew up semi-poor, in which they say that they “came from a middle-class background…” (which of course implies that they’re now upper-middle class…) I never hear anyone claim to be upper-class, lower-class, or lower middle-class. Anyway, my parents always said we were upper middle-class, so I guess that’s why I say it too.

B

The next point in the Wedge is mighty Mirfak. From Epsilon to Delta Persei, continue along the same line, except veer ~30 degrees to the West. Continue a bit less than half the apparent Epsilon-Delta distance and you hit honking bright Mirfak.

As I mentioned earlier, Mirfak is the alpha star of Perseus only due to the dust obscuring Epsilon Persei. It’s a young, hot star, maybe 30- 50 million years old, shining 5,000 times as brightly as our sun and lying some 590 light-years distant, and…. waaaait a minute. Isn’t this sounding familiar? All 3 of these stars are super-bright, super-young, and about the same distance- rather atypical for a named constellation. Almost Big Dipper-ish*, in fact. What’s going on here?

As I mentioned earlier, Mirfak is the alpha star of Perseus only due to the dust obscuring Epsilon Persei. It’s a young, hot star, maybe 30- 50 million years old, shining 5,000 times as brightly as our sun and lying some 590 light-years distant, and…. waaaait a minute. Isn’t this sounding familiar? All 3 of these stars are super-bright, super-young, and about the same distance- rather atypical for a named constellation. Almost Big Dipper-ish*, in fact. What’s going on here?

*I blogged all about the Big Dipper in this post.

Mirfak, Delta Persei, and Epsilon Persei are all part of the same open star cluster*, the Alpha Persei Cluster, which is around 50 million years old. If you check out Mirfak through binoculars, you’ll see the space around it appears packed with other blue-white members of this cluster.

*I explained open star clusters in this post. Man, it is like I have a post for everything.

As I lay in my bag I retraced the line from Epsilon Persei to Delta Persei, then from Delta Persei to Mirfak, repeatedly, becoming comfortable with the lay of three stars above. As I did so, I started to think of Epsilon -> Delta as segment “A”, and Delta -> Mirfak as segment “B”. Now I was ready to look for “C”.

Engineering seemed dry and dull, and the raises small, so I switched to sales after a couple of years, lured by the promise of big commissions. I wasn’t particularly good at it, but I knew my product well and stumbled into enough lucky breaks to make that first job work, which lead to another job and another… In that first job I used to fly a couple of times a month, mostly between Boston and Newark. One time I was waiting for a flight and I noticed another salesguy-looking fellow waiting. He looked really old, like maybe 45 or something, and I remember thinking, “Man, I hope I’m not still flying around selling stuff when I’m 45…”

My career progressed well enough, making a good living and moving into management, but I never quite hit it big enough to check out. Almost 20 years after I saw that 40-something salesguy in the Newark airport, I lay under the stars, thinking about my life, and about the maybe, possibly, finally chance to break free…

C

“C” is a direction reversal, heading back South from Mirfak, but veering ~30 degrees West of due South, down almost as far South as Epsilon Persei, down to the next bright star, Algol. In the traditional rendering of the constellation, Algol- the apparent 2nd-brightest star- is the eye of Medusa, the thing that when you look straight at it, will turn you to stone. But although it won’t really turn to stone, Algol will, if you look long enough at it, wink at you.

Algol is different than the other 3 stars of the wedge. It’s not part of the Alpha Persei Group, and it’s nowhere near as bright as they are. It’s 100 times as bright as our sun, and only appears so bright relative to the other 3 wedge-stars because it’s so much closer- only 93 light-years. Most of the time, Algol shines as a second magnitude star, and the second-brightest star in Perseus, But roughly once every three days, it gets noticeably dimmer (by 2/3!) for a few hours, then returns to normal.

Algol is different than the other 3 stars of the wedge. It’s not part of the Alpha Persei Group, and it’s nowhere near as bright as they are. It’s 100 times as bright as our sun, and only appears so bright relative to the other 3 wedge-stars because it’s so much closer- only 93 light-years. Most of the time, Algol shines as a second magnitude star, and the second-brightest star in Perseus, But roughly once every three days, it gets noticeably dimmer (by 2/3!) for a few hours, then returns to normal.

Algol is an eclipsing binary, and was in fact the first such system to be discovered. It consists of 2 stars orbiting each other very closely (less than 5 million miles apart- about 1/20th the distance between the Sun and the Earth) and very rapidly (once every 2.867 days) on a plane parallel to our line-of-sight from Earth, such that one passes in front of the other roughly every day and a half. The star we see is a main sequence hydrogen-burner, like our own sun, only 3.5 times as massive. The obscuring star is a burnt-out giant, dim, with a mass of 0.81 times that of our sun.

Wait a minute- big stars burn out faster. Why is the burnt-out partner the less massive one? Because at their close distance, the burning-bright star is sucking away matter from the dying hulk of its burnt-out partner. It only steals a teeny-tiny fraction of its mass away every year, but at the current rate it should suck it away completely in around 40 million years.*

*My calculation, could be wrong.

There’s a third partner in the Algol system, about twice the mass of our sun, orbiting the inner 2 stars once every couple of years at about the same distance as between our sun and the asteroid belt. None of the Algol system stars are known to possess planets, but if they do, their skies must be freaky-wild.

There’s a third partner in the Algol system, about twice the mass of our sun, orbiting the inner 2 stars once every couple of years at about the same distance as between our sun and the asteroid belt. None of the Algol system stars are known to possess planets, but if they do, their skies must be freaky-wild.

The Big Deal

The maybe-possibly part was the promise of a deal- a big deal. A company-liquidity kind of deal that would make my hard-earned piece of it worth something. For 6 years I’d stayed with the same company in hopes of just such a deal, though it seemed forever to lie out of reach, and for the last year I’d debated whether to stick around or move on. Start over. Hit the reset. Find a new gig, negotiate a new deal with a new company, start working and vesting all over again, and hope for a better outcome.

But now, for the first time, that deal was on the horizon. And as I thought about that deal, and about the course of my life and my passion and paths, I re-traced again and again the 3 segments of the wedge of Perseus in the sky above- from Epsilon Persei to Delta Persei to Mirfak to Algol- and a thought came into my head: that the deal- when it happened- would be akin to “A”, in that it would enable a step “B” and a step “C” that would give me the freedom and opportunity and security and confidence to break out of the LQC and start to realize the passions and interests I’d come to recognize only in the middle of my life. Specifically what “B” and “C” were, how they were connected, and what would they would entail aren’t important, but they lead to the promise of a lifestyle of more time doing things that I’d finally figured out were important, including, but not limited to, spending more time doing things I love, traveling to places I’d always daydreamed about traveling to, being a better friend, spouse and parent, and finally paying attention to, learning about, and understanding something of, the natural world around me. Maybe I’d start by creating a blog to keep track of various trees, shrubs and wildflowers as I learned to ID them…

In my head it all fit together, and I called the plan (to myself only) “ABC in Perseus.” ABC in Perseus was my vision, my path, my ticket to freedom, balance and a better, more fulfilling life. And after I returned home, dealing with the craziness of work and the mechanics and logistics of the hoped-for “A”, I kept that vision in my head. “ABC in Perseus”, I’d remind myself, when stressed or worried, and sometimes in the evening I’d step out onto the back porch before bed and scan the night sky, just to reassure myself that ABC was still there. And so things went forward for the next 2 months.

In mid-March 2008, the deal fell- quickly and spectacularly- apart. There was no backup plan, no successor deal on the horizon. I was deflated, crushed, the mental wind knocked out of me. On the verge of Spring- a Spring I’d so been looking forward to- I grasped about for some kind of outlet or distraction, something to focus on other than my lack of a plan or direction. Two weeks later I started this blog.

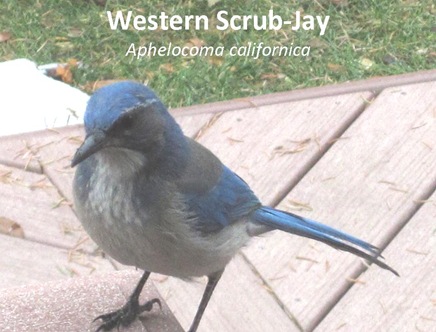

The “project” started out as a way to learn about flowers, shrubs and trees. I thought I’d do it through the Spring. But Spring came and went and there were still new flowers and trees to check out, and when I learned about them, it seemed that nearly all of them had a cool story. As I learned more about them, I started to get curious about their relationships to one another, and then to and with other living things- other growing things, like mosses and lichens, as well as moving things, like birds and bugs and other critters.

Summer turned to Fall to Winter to Spring again and I still wasn’t done checking out flowers and shrubs, and now I was interested not just in other living things but in their connections to the non-living world, and things like light and sound and rocks and magnetic force and water and the connections between those things and the universe as a whole, and… well, if you’ve been following along over the course of this project you already know all this.

The Big Deal, Take 2

Seasons continued to pass, work continued to happen, and after another couple of years, after the first Big Deal was a faint memory, another Big Deal did appear. And as it developed and grew and then finally came together, it occurred to me that this was “A” all over again, and that if I kept my nose down and played things right, ABC in Perseus could still happen.

Over the last year, “B” and “C” did happen, and though I won’t get into details, I’ll say that it was a year of keeping cool, threading needles and juggling balls. And for once in my long, wandering, figuring-it-out-as-I-go-along life, I did everything right*. ABC in Perseus completed last week. My last day with the company will be January 31. I don’t really need to work, well… anymore.

*Part of “B&C” did involve money, and another part involved disentangling oneself without burning bridges. But the most important part involved finding homes for my team in the new entity. The truth about acquisitions is that they’re great for the top guys, but often a raw deal for the rank & file. M&A folks talk about synergies and opportunities, but for the average worker-bee, having your employer acquired is usually not a good deal. At the time of the acquisition I managed around 30 people, and it was important to me that, at the end of the integration-year, they wound up with good, secure jobs. My success rate ended up being about 90%. (As recently as Thanksgiving, it was looking more like 60%. I did a lot of fast talking and fancy footwork this holiday season…)

To be clear, I will work again. Life is long, children are expensive and the future full of unknowns. But not yet. I’ve put too many things off for too long, and now… well, we’ll get to that soon enough.

All About Money Part 2- How Money Is Like Nudity. And Some Other Stuff.

Tangent: Here’s a funny thing about money: you hardly ever tell other people how much you have or make. Even your good friends. Think about it- married middle-aged guys are more likely to share details of their/their wives’ sex lives with each other with their friends than they are how much money they make. Isn’t that weird? But you (assuming you’re a guy- I can’t speak for women) know it’s true! Why is that? And yet, there are some people in front of whom we speak of our incomes freely. We talk about it with our boss of course, but also our accountant, and maybe our financial planner. Yet we don’t talk about it with our good friends, whom we know far better than our accountants. Why is money like that?

Know what else is like that? Getting nekkid. Most of us don’t get naked in front of most other people, including our friends. But when we go to the doctor- even a strange or new doctor we’ve never seen before- we happily disrobe in front of him/her. You may say, oh, well that’s health-related, it’s private. Maybe, but people share (or overshare) exacting details of their various health ailments all the time with all sorts of people. But they don’t get naked in front of them. Why are only Money and Nudity like that? Nudity of course has the whole connection to Sex. OK, so why are Money and Sex these 2 big, weird taboo topics, when making money and having sex are probably the only 2 things the vast majority of adult humans have in common?

Mind you, I’m not advocating that people should walk around naked telling each other how much money they make- I’m just saying it’s weird.

Where was I going with this tangent? Oh yeah- so anyway, one of the interesting things about this upcoming break is people’s reactions to it. Some are happy for me, some are envious, and others just confused, all of which are fine and understandable. But the reaction of a fair number of people has been a sort of denial. “Well, there’s no way I could stop working now- I just don’t know what I’d do with myself!”, they harrumph... I’m never really sure where this reaction is coming from. On the one hand, maybe it’s a face-saving thing: they’d like to stop rat-racing, but can’t see a way how to, so they tell themselves that they wouldn’t want out, even if they could finagle it… But on the other hand, maybe they really mean it. Which on the one hand is just great. Maybe they’re an artist, a researcher, educator, astronaut, Leader of the Free World, Rock Star or something else that brings them meaning and fulfillment. But when I hear it from a salesman or a purchasing agent or a product manager, I scratch my head a little; is there really nothing else, no other passion or interest or calling that you’d rather be following 40, 50 or 60 hours a week?* (And if not, doesn’t that give you pause?)

*I’ll probably piss off some reader with this one, and half-expect some “I love my job” comments. Which is great, and I hope you do (love your job- though I certainly welcome your comments as well.). But before you claim that you do your job because it’s how you want to be spending your time, ask yourself this: If you got paid the same whether you showed up for your job or not, or if you had X million bucks in the bank, would you still do it?

One more thing about money: It’s often said- and is very true- that money doesn’t bring happiness. But, ironically, the lack of money brings tremendous unhappiness. Isn’t that strange?

I love movies and stories where guys ride off into the sunset. My absolute favorite is the end-scene in Pulp Fiction, where the enforcer/hit-men played by John Travolta and Samuel Jackson are talking over breakfast. Samuel Jackson tells John Travolta he’s quitting, leaving the business, he’s getting out. Travolta, incredulous, asks him what he’ll do, and Jackson says, “You know, walk the Earth, meet people and get into adventures. Like Caine from Kung Fu.”

I love that line. And that- more or less- is what I’m going to do. Oh, it’ll be a little more tamped-down; I do have a wife and kids and home and such. But for the next year, I (along with my family a good part of the time) am going to walk (and bike and ski and drive and take airplanes around at least some limited portions of) the Earth, meet people and get into adventures.

I love that line. And that- more or less- is what I’m going to do. Oh, it’ll be a little more tamped-down; I do have a wife and kids and home and such. But for the next year, I (along with my family a good part of the time) am going to walk (and bike and ski and drive and take airplanes around at least some limited portions of) the Earth, meet people and get into adventures.

All of which brings me back around to this project, this blog, and well, uh… us.

Next Up: We Have To Talk

Note About Sources: Info for this post came from Jim Kaler’s totally awesome STARS site, the Audubon Society Field Guide to the Night Sky, the Sky & Telescope Magazine website and Wikipedia.

![Perseus Andromeda Action Graphic[4] Perseus Andromeda Action Graphic[4]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgsMFqOjVG1NMAOartJ4I5yXiiKZUjtPwgRf-sfkjrB2SZxoQkgtJKYzsku4qQ2Ojyy676FlVSZmN9_kGfkMlOHURWvDI31NSDmA98QldGniPqXbuAchiybZHqv1hG0ekjTFFxCUliG_IY/?imgmax=800)

and which appears in about 10% of humans, including- yes, that’s right- me!* It’s called Darwin’s tubercule, and is a slight thickening/protuberance of the rim of the pinna, about 2/3 of the way up (2 o’clock on the left ear, 10 o’clock on the right.) it corresponds to the point of pointy-eared mammals, and is believe to be a vestigial remnant of our presumably pointy-eared ancestry. Sometimes it’s more of a bump or protuberance pointed away from the ear canal, creating an almost Spock-like effect.

and which appears in about 10% of humans, including- yes, that’s right- me!* It’s called Darwin’s tubercule, and is a slight thickening/protuberance of the rim of the pinna, about 2/3 of the way up (2 o’clock on the left ear, 10 o’clock on the right.) it corresponds to the point of pointy-eared mammals, and is believe to be a vestigial remnant of our presumably pointy-eared ancestry. Sometimes it’s more of a bump or protuberance pointed away from the ear canal, creating an almost Spock-like effect.

![Syrinx Expand-O[9] Syrinx Expand-O[9]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgne-Gb_yEYJmGRbkEnGpy4y6PSiB7ILuiou36t4GJOiV6qNGvz8NB5sWFKCN6IJbF-pHDuyZ7MGmcRyk7NiSD9MAJhyI-9FZJUUrTDPCIkavlDLChyB8NNmLvdaqG9jkBopm1dQ-cBe6A/?imgmax=800)