So 2 things real quick. First, this has been kind of a cool week. On Saturday I kicked ass in a brutal race (a 15 mile hill-climb) It was one of those climbs that everything clicked for me, and my finishing time put me 3rd place in the Cat 4’s and was better than any of my teammates (including several who really are stronger/better riders…) As a result, all this week I’ve been getting “well done/nice job” type emails from friends and teammates and have been feeling generally on top of the world.

So 2 things real quick. First, this has been kind of a cool week. On Saturday I kicked ass in a brutal race (a 15 mile hill-climb) It was one of those climbs that everything clicked for me, and my finishing time put me 3rd place in the Cat 4’s and was better than any of my teammates (including several who really are stronger/better riders…) As a result, all this week I’ve been getting “well done/nice job” type emails from friends and teammates and have been feeling generally on top of the world.

Second, I’m flying East tonight for 10 days in Massachusetts and Maine. My wife and kids are already back East in NJ with her family and will fly up to meet me in Boston Friday. (Pic left of #2 Son aka ”Twin A” buried in NJ beach sand…)The first 2 days of my trip are work; next week is vacation. I grew up in the suburbs of Boston, and my folks and brother still live there, so this will be a trip to catch up with family. Later in the week we’ll head up to Southwestern Maine, where my Dad built a cabin on a lake 35+ years ago for a few days of swimming, sailing and canoeing.

Second, I’m flying East tonight for 10 days in Massachusetts and Maine. My wife and kids are already back East in NJ with her family and will fly up to meet me in Boston Friday. (Pic left of #2 Son aka ”Twin A” buried in NJ beach sand…)The first 2 days of my trip are work; next week is vacation. I grew up in the suburbs of Boston, and my folks and brother still live there, so this will be a trip to catch up with family. Later in the week we’ll head up to Southwestern Maine, where my Dad built a cabin on a lake 35+ years ago for a few days of swimming, sailing and canoeing.

I have mixed feelings about the trip. I’ve been really into the Wasatch this summer, and there’s a lot to do, see and blog about here. But I’m also ready for a break from Utah. I wouldn’t mind a little more green, and I love natural lakes, which are lacking in this part of the country. While I’m gone I’ll try to blog a bit, but I’m not sure if I’ll continue the “Piney-Looking Tree” series, or blog about stuff back East…

Enough Rambling – Let’s Talk Trees

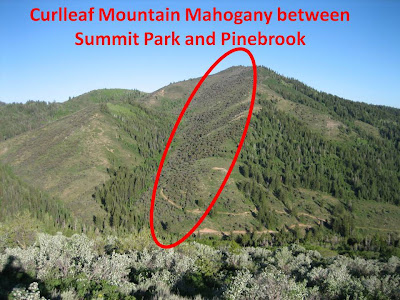

So seeing as pretty much all my biking and hiking these days (OK biking really- I am riding my ass off but haven’t hiked in a month+) is up over 7,000 feet, we should talk about trees. Because even though I’m still often riding past the same 3 “Foothill Friends”- Gambel Oak, Bigtooth Maple, and Curlleaf Mountain Mahogany, they’re not the dominant trees over 7,000 feet.

The good news about the trees over 7,000 feet is that they are absolutely, indisputably, real trees. Not oversized shrubs, or thickets, but real trees with real shade. And in the summer in Utah, it’s all about shade.

The good news about the trees over 7,000 feet is that they are absolutely, indisputably, real trees. Not oversized shrubs, or thickets, but real trees with real shade. And in the summer in Utah, it’s all about shade.

One of the great things about living in a part of the country with minimal floristic diversity is that you can quickly learn what few tree types grow naturally in a given milieu, and then be filled with boundless self-confidence as you confidently identify those trees. And certainly when you compare the forests of the Wasatch with the forests of the Sierras or the Appalachians, they’re pretty species-poor. But those we have are wonderful and worth knowing.

At the highest level, there are 2 broad divisions of Wasatch trees: Aspen and Conifers. Aspen are easy. If you can’t recognize them, go back to New Jersey. And we’ll talk about Aspen soon enough, but first let’s look at the Conifers, or as I often think of them, the “Piney-Looking” trees.

There are loads of coniferous trees in the Wasatch, but the good news for a wannabe botanist is that the vast majority of them are of just 3 species. And none of those species is actually a “Pine.” (There are pines in the Wasatch, but we’ll come to them- and their problematic distribution- later.) The three are a Fir, a Douglas Fir, and a Spruce. And the 3 look pretty similar, especially from a distance, until you know what to look for. So in this post I’ll talk about how to identify the 3 from one another, and then in subsequent posts we’ll look at each in a bit more detail.

But first, what is a “Piney-looking tree?”

Way back when, we talked about how pretty much all trees are either Angiosperms (flowering plants) or Gymnosperms (no flowers.) And we talked about how Angiosperms have pretty much conquered the world, but that Gymnosperms, despite far fewer species, still dominate large areas of the planet. The largest (by far) division of gymnosperm trees are the Conifers. There are over 600 species of conifers and they include all of the Pines, Spruces, Firs, Douglas Firs, Junipers, Redwoods, Larches, Cedars, Hemlocks and a bunch of other stuff that grow way far away, like Araucarias (think “Norfolk Pine”.) Within the Conifer “Division”, the largest “Family” is the Pine Family, or Pinaceae, with ~250 species across 11 genera. 4 of those genera- Pine (Pinus), Spruce (Picea), Fir (Abies) and Douglas Fir (Pseudotsuga) occur naturally in Utah

Background on Pine Taxonomy

Most people, when they think about pines at all, assume that any tree with needles is a “pine tree”, which is not the case. Pines are evergreen conifers that bear cones, and whose needles are clustered together in little bundles called fascicles, which connect the needles to the branch. Spruces, firs, Douglas firs, hemlocks and most everything on a Christmas tree lot are not pines. But they’re all members of the Pine Family, so we’ll refer to them as “Piney-Looking Trees”.

Tangent: Many people also assume all Conifers are evergreen. Most are, but not all. Larches for example are deciduous. (There are no Larches in Utah, but they occur as close as Northern Idaho.)

The 3 main players of the Wasatch Conifers represent 3 of those 4 genera, and what’s interesting is that even though they all look similar, they haven’t shared a common ancestor since dinosaurs walked the Earth, well over 100 million years ago. In other words, they’re about as closely-related to each other as we are to Kangaroos. Another interesting thing about them is that looking at them, you’d assume that they’re all more closely-related to one another than they are to Pines, which look noticeably different.

But DNA research (on nuclear, mitochondrial and chloroplast DNA) in recent years indicates that Spruces are more closely related to Pines than to Firs or Douglas Firs, and Douglas Firs in turn are more closely related to Pines and Spruces than they are to the very-similar-looking “True” Firs.

And what’s really interesting, is that here we are in the Wasatch, like 150 million+ years later, in a totally changed world, and each one of these very distinct genera has evolved a species that is a major player in the Wasatch, standing side-by-side, duking it out.

Identifying Pine-Looking Trees

So, how do you tell them apart? The two best tools are cones and needles. Cones are easiest, but they’re not always there, so needles are your back-up. First cones. If the tree has cones hanging downward from its branches, it’s either a Douglas Fir, Pseudotsuga menziesii, or an Engelmann Spruce, Picea engelmannii.

White Fir, Abies concolor, like all “True” Firs has cones that stand straight up from the branch, and occur only on the highest branches- not down at eye-level. Fir cones don’t drop either- they disperse their seeds and then disintegrate on the tree. So chances are, you’ll never see a White Fir cone close up.

Absence doesn’t prove anything, but with the downward-hanging cones, you know the tree is a Douglas Fir or an Engelmann Spruce.  The cones are roughly the same size, but have an important difference: Douglas Fir cones have small, 3-pointed bracts (miniature, specialized leaves) sticking out from between the scales of the cone. Engelmann Spruce cones have no bracts.

The cones are roughly the same size, but have an important difference: Douglas Fir cones have small, 3-pointed bracts (miniature, specialized leaves) sticking out from between the scales of the cone. Engelmann Spruce cones have no bracts.

The obvious problem with cones is that they’re only an identifier when they’re there, and Spruce and Douglas Fir don’t always have cones hanging off them. (Oftentimes, cones on the ground below the tree can be a clue, but this can be tricky in a mixed stand.) But all three of these trees always have needles.

Pluck a needle from the tree in question and hold it between your thumb and forefinger. Try to “roll” the needle between your finger pads. If it ”rolls” successfully, that’s because it’s 4-sided, and therefore an Engelmann Spruce. Most Spruces have 4-sided needles (Norway Spruce needles are 3-sided and Sitka Spruce needles are flat, but neither occurs here in Utah. So, like smooth, hairless Wyethia leaves, this trick works in Utah, but not everywhere.)

If the needle doesn’t roll, it’s because it’s “flat”, or 2-sided, which means it’s either White Fir or Douglas Fir. To determine which of the 2 flat-siders it is, look at how the needles are attached to the branch. White Fir needles connect with a clear, round “landing pad”, and the needle stays almost as wide all the way down to the base. Douglas Fir needles (pic left) narrow to a tiny stalk in the last ½ a millimeter as you go toward the base, and it’s this little stalk that attaches them to twig.

If the needle doesn’t roll, it’s because it’s “flat”, or 2-sided, which means it’s either White Fir or Douglas Fir. To determine which of the 2 flat-siders it is, look at how the needles are attached to the branch. White Fir needles connect with a clear, round “landing pad”, and the needle stays almost as wide all the way down to the base. Douglas Fir needles (pic left) narrow to a tiny stalk in the last ½ a millimeter as you go toward the base, and it’s this little stalk that attaches them to twig.

More Subtle Differences

Fir and Douglas Fir needles generally grow in two “rows” long either side of the twig. Spruce needles grow out from the twig perpendicularly, but in all directions- sideway, up, down or in-between, making Spruce twigs look more like bottle brushes than Fir or Douglas Fir twigs.

Subtle Differences From a Distance

The bark of mature Engelmann Spruce takes on a subtle reddish/pinkish/orangey tone (pic right). Once you recognize it, it’s a cinch to identify.

The bark of mature Engelmann Spruce takes on a subtle reddish/pinkish/orangey tone (pic right). Once you recognize it, it’s a cinch to identify.

When White Fir and Douglas Fir occurs together, such as in Porter Fork, I’ve noticed that in the Winter the Douglas Fir needles have a slightly yellower tone than the White Fir needles. I’ve only noticed this in Winter.

Lastly, the foliage of Engelmann Spruce and Douglas Fir is denser than that of White Fir. The forest floor under the 2 former trees feels shadier, darker, and a bit less “friendly” than the floor under White Fir. This “density” of foliage means they provide better rain protection, should you need to wait out a quick shower in the backcountry (standard lightning safety rules apply.) In mixed Douglas Fir/White Fir country, a stand of pure Douglas Fir may manifest itself as an especially dry, dusty stretch of deeply-shaded trail.

Now to be clear, these 3 guys are not the only conifers in the Wasatch- just the most common. Next we’ll check out each in turn, and in doing so, mention a few of the “bit players.”