I have a “real” post today, and it’s a cool one. But I can’t start into it without first observing the passing of Ricardo Montalban.

Tangent: I loved Ricardo Montalban, and here’s why: He had the Best Accent Ever. Charming, elegant and melodious, his accent was simply captivating.

I’ve always wished that I could sound like Ricardo Montalban when I spoke a foreign language, so that native-speakers would be immediately taken with my presence, sophistication and je ne sais quoi. But the only other language I speak (poorly) is Spanish, and I’ve had enough frank conversations with native Spanish speakers to know that an American accent is not pleasing to the Spanish ear.

I’ve always wished that I could sound like Ricardo Montalban when I spoke a foreign language, so that native-speakers would be immediately taken with my presence, sophistication and je ne sais quoi. But the only other language I speak (poorly) is Spanish, and I’ve had enough frank conversations with native Spanish speakers to know that an American accent is not pleasing to the Spanish ear.

Now in English, different accents sound more pleasing than others. Most of us native English-speakers would agree that we find a French accent, for example, more appealing than a Russian, Indian or Chinese accent. So my question is this: In what foreign language does speaking with an American accent make me sound like Ricardo Montalban to the native-speakers? Because wherever that country is, if I ever find out, I am dropping everything, moving my ass there, learning the language and spending the rest of my days exuding silky charm, elegance and sophistication.

Adiós, Don Ricardo. Que le vaya bien.

The Real Post

I post a lot of photos in this blog. Usually they’re intended to be helpful, to give the reader a feel of the place or thing I’m blogging about, and sometimes they’re just to show off me or my kids, or poke fun of my friends. In any case, they’re usually not essential to the story; I just like stories with pictures, and I assume other people do as well.

This photo’s different. Though it’s one of the least impressive photos to appear in this blog, you need to look at it to get the post.

I took this photo on a morning following a storm last week from the Olympus Cove shopping center parking lot, right off of I-215. The ridge in the foreground in Stansbury Island in the Great Salt Lake. The high peak rising behind it is Pilot Peak, just across the state line in Nevada, about 15 miles North/Northwest of Wendover. I shot the photo with 12X magnification (hence the lousy quality.) The distance from the Oly Cove parking lot to Pilot Peak is 119 miles.

I took this photo on a morning following a storm last week from the Olympus Cove shopping center parking lot, right off of I-215. The ridge in the foreground in Stansbury Island in the Great Salt Lake. The high peak rising behind it is Pilot Peak, just across the state line in Nevada, about 15 miles North/Northwest of Wendover. I shot the photo with 12X magnification (hence the lousy quality.) The distance from the Oly Cove parking lot to Pilot Peak is 119 miles.

History-Tangent: Pilot Peak (pic left = Pilot Peak seen from Desert Peak, high point of Newfoundland Range) is so named because it’s the landmark that westward-bound pioneers aimed for when crossing the 80-mile waterless stretch of salt/mud flats on the route known as the Hastings Cutoff.  The springs at the base of Pilot Peak provided the first water at the end of that stretch, and the path across the salt flats leading toward the Peak were littered with dead livestock, stuck/broken wagons, and abandoned gear. The Hastings Cutoff was the path followed by the Donner Party. Though they had a difficult time across the salt flats, the delay that caused their eventual misery in the Sierra happened a week or so earlier, when they spent several days hacking a road down Emigration Canyon.

The springs at the base of Pilot Peak provided the first water at the end of that stretch, and the path across the salt flats leading toward the Peak were littered with dead livestock, stuck/broken wagons, and abandoned gear. The Hastings Cutoff was the path followed by the Donner Party. Though they had a difficult time across the salt flats, the delay that caused their eventual misery in the Sierra happened a week or so earlier, when they spent several days hacking a road down Emigration Canyon.

Pilot Peak is the furthest thing you can see from the Salt Lake Valley. It’s only visible on clear days, which is why I always make a point of looking for it the morning after a storm.

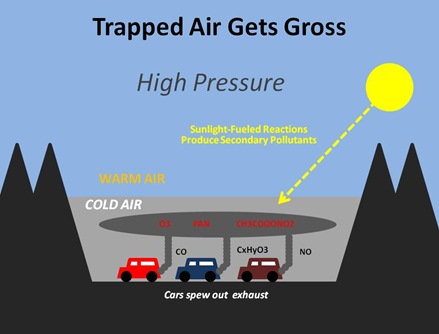

Tangent: Everyone who lives along the Wasatch Front knows that storms clear out inversions and pollution. Much of this clarity comes of course from the disruption of the thermal layers that constitute an inversion.

Nested Tangent: I plan to do a post on inversions, where I explain what’s going on with them and why they’re so darn interesting, even if they are gross and cold. There just hasn’t been a bad one yet this year to blog about. But I’ll get to it.

Nested Tangent: I plan to do a post on inversions, where I explain what’s going on with them and why they’re so darn interesting, even if they are gross and cold. There just hasn’t been a bad one yet this year to blog about. But I’ll get to it.

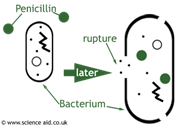

But the other reason for the clarity is that precipitation actually removes particulate matter from the atmosphere, and the reason for this is that both snowflakes and raindrops typically form around a bit of dust at their center, and so as billions of snowflakes/raindrops are formed and fall to the ground, billions of little particles are “pulled down” along with them. I explained the mechanism of snowflake formation around a dust particle back in October, so I won’t repeat it here, but you can check out that post if you’re interested.

When you grow up in the East and then relocate to the West, you never stop being amazed by How Far You Can See. 119 miles. That’s as if from the house I grew up in, in the suburbs of Boston, I could see clear to Albany, New York. That is astounding. I never cease to be amazed by it, and I am equally amazed that the million or so people in this valley with me hardly seem to notice.

Tangent: What really amazes me about my valley-mates (and is probably more properly the topic of another post, but when did that ever stop me from going off…) is how they can live for decades under the shadow of these fantastic peaks- Lone Peak, Timpanogos, Pfeifferhorn, Twin Peaks, Olympus, Ben Lomond, Nebo- and never climb them. How can they bear it? To never see how grand and majestic and utterly magnificent our valley is from these peaks- Isn’t it torture?

Tangent: What really amazes me about my valley-mates (and is probably more properly the topic of another post, but when did that ever stop me from going off…) is how they can live for decades under the shadow of these fantastic peaks- Lone Peak, Timpanogos, Pfeifferhorn, Twin Peaks, Olympus, Ben Lomond, Nebo- and never climb them. How can they bear it? To never see how grand and majestic and utterly magnificent our valley is from these peaks- Isn’t it torture?

Nested Tangent: Yes, I’ve climbed (nearly) all of them, a topic I’ll return to later in the post, probably in yet another tangent…

To see things 50 or 100 miles away- and know what you’re seeing- gives you a sense of scale and feel for the landscape that you don’t get if you live your life in places where you can’t see faraway things. And if you’ve actually stood atop the point you’re looking out at, then that sense and feel is an order of magnitude clearer.

In October, 2002 I climbed Pilot Peak. It’s a trail-less scramble, typical of so many West Desert climbs, only higher, at nearly 11,000 feet. (For a more detailed description of the methodology and experience of such climbs, see this post.)  From the summit I could see West to the crest of the Ruby Mountains, where I’ve also stood. (pic right = Liberty Lake, in the Ruby range.) From the Ruby summits you can look down into the Humboldt valley and Elko, NV. That’s a continuous line of site- with just 3 segments- from the Oly Cove shopping center to Elko, NV, a distance of ~200 miles.

From the summit I could see West to the crest of the Ruby Mountains, where I’ve also stood. (pic right = Liberty Lake, in the Ruby range.) From the Ruby summits you can look down into the Humboldt valley and Elko, NV. That’s a continuous line of site- with just 3 segments- from the Oly Cove shopping center to Elko, NV, a distance of ~200 miles.

I’m just getting started.

From the summit of Pilot, if you turn South you’ll see Ibapah Peak in the Deep Creeks (pic left), which I climbed back August, 2004. From Ibapah you can see 13,000 ft Wheeler Peak, further South, in Great Basin National Park, which I climbed in October, 2005. From Wheeler Peak you have a clean line-of-sight to Notch Peak (climbed May, 1998 and October, 2005) in the House Range, back East across the UT state line.

From the summit of Pilot, if you turn South you’ll see Ibapah Peak in the Deep Creeks (pic left), which I climbed back August, 2004. From Ibapah you can see 13,000 ft Wheeler Peak, further South, in Great Basin National Park, which I climbed in October, 2005. From Wheeler Peak you have a clean line-of-sight to Notch Peak (climbed May, 1998 and October, 2005) in the House Range, back East across the UT state line.

Tangent: Notch Peak is unbelievably dramatic; its West side is a sheer, 3,000 foot cliff, far and away the biggest, scariest, most awesome cliff East of Yosemite. (pic right = looking down 3,000 ft cliff en route to peak.) The climb is a piece of cake (<2 hours hiking) and offers an easy side hike to an outstanding ancient Bristlecone Pine forest. There’s never anyone there, and I know hardly anyone else who’s been there. Utah readers: Go do it- you will be blown away.

Tangent: Notch Peak is unbelievably dramatic; its West side is a sheer, 3,000 foot cliff, far and away the biggest, scariest, most awesome cliff East of Yosemite. (pic right = looking down 3,000 ft cliff en route to peak.) The climb is a piece of cake (<2 hours hiking) and offers an easy side hike to an outstanding ancient Bristlecone Pine forest. There’s never anyone there, and I know hardly anyone else who’s been there. Utah readers: Go do it- you will be blown away.

From the crest of the House range you can look back East to the crest of the Tushars behind Fillmore and Beaver.

Tangent: If you’re a Utah mtn biker, add the Skyline Trail East of Beaver to your must-ride list (pic right). Rugged, challenging singletrack though pristine spruce/fir forest with plenty of great views.

Tangent: If you’re a Utah mtn biker, add the Skyline Trail East of Beaver to your must-ride list (pic right). Rugged, challenging singletrack though pristine spruce/fir forest with plenty of great views.

From the Tushar crest you can see clear to the Aquarius Plateau, which sort of merges into Boulder Mountain on its Eastern side. I’ve been all over the Aquarius and Boulder Mountain on several trips over the years.  From Boulder Mountain you can easily see the Henry Mountains (last range in the lower 48 to be mapped) to the East. I climbed the high point of the Henrys, 11,000 ft Ellen Peak, in September 1995. From there you can look East to the La Sals (high point = Mt. Peale, climbed June, 2006) or Southeast to the lower Abajo Mountains, just West of Monticello. (pic left = Abajo range, seen from Mt. Peale)

From Boulder Mountain you can easily see the Henry Mountains (last range in the lower 48 to be mapped) to the East. I climbed the high point of the Henrys, 11,000 ft Ellen Peak, in September 1995. From there you can look East to the La Sals (high point = Mt. Peale, climbed June, 2006) or Southeast to the lower Abajo Mountains, just West of Monticello. (pic left = Abajo range, seen from Mt. Peale)

Tangent: Ellen Peak is so easy a climb, you could practically do it in your flip-flops. You start at Bull Creek Pass, and it’s maybe a mile and a half of super-mellow climbing, great views the entire way.

On a clear day in September, 1993, from a minor summit in the Abajos, I spied Shiprock, the sandstone monolith outside the namesake town, in Northwestern New Mexico.

That’s a continuous (if circuitous) line of sight from my home to Shiprock, NM, a crow-fly distance of ~340 miles. I’ve done similar lines of sight East to Grand Mesa, CO, North to the Sawtooths in ID, all over Southwest UT and Southern NV to Las Vegas, and a cool one from Organ Pipe Nat’l Monument to the Sea of Cortez.

That’s a continuous (if circuitous) line of sight from my home to Shiprock, NM, a crow-fly distance of ~340 miles. I’ve done similar lines of sight East to Grand Mesa, CO, North to the Sawtooths in ID, all over Southwest UT and Southern NV to Las Vegas, and a cool one from Organ Pipe Nat’l Monument to the Sea of Cortez.

And this brings me to the point of this post, and my dream line-of-sight project: a continuous line of sight from my home in Salt Lake to the Pacific Ocean.

I’ve got a good start, with a solid line out to the Rubies. I’ve also been on the Toiyabe Crest (pic right), and could probably make a Toiyabe – Ruby connection with just 2 climbs. From the Toyaibe Crest I could probably make the Sierras in 2 climbs, the first one maybe being the Desatoya range, which I noted on our Cross-basin road trip back in August.

I’ve got a good start, with a solid line out to the Rubies. I’ve also been on the Toiyabe Crest (pic right), and could probably make a Toiyabe – Ruby connection with just 2 climbs. From the Toyaibe Crest I could probably make the Sierras in 2 climbs, the first one maybe being the Desatoya range, which I noted on our Cross-basin road trip back in August.

For the Sierras I’d need a bit more research. They’re a wide range, so I’d probably need to do at least 2 summits, and the other problem is summiting at a point where I could see across the Central Valley to one of the Coast ranges. This part would be easier if I summited further North, where the Central Valley narrows a bit, but the coast ranges up North get “fatter” and merge with full-on inland ranges, like the Trinity Alps.

For the Sierras I’d need a bit more research. They’re a wide range, so I’d probably need to do at least 2 summits, and the other problem is summiting at a point where I could see across the Central Valley to one of the Coast ranges. This part would be easier if I summited further North, where the Central Valley narrows a bit, but the coast ranges up North get “fatter” and merge with full-on inland ranges, like the Trinity Alps.

So the California part isn’t yet clear, but the Salt Lake to Sierra Crest connection is within my grasp.

Tangent: This is as good a time as any to mention another, almost-completed, project: the Every Peak I See Project. Sometime in 1997 I was out in the middle of the Salt Lake Valley, running an errand or something, and I took a moment to look around. I decided then that I wanted to climb every major peak visible from the valley floor. I’ve done all but 3. Red dots on the map below indicate valley-floor-visible peaks I’ve climbed, yellow dots indicate the remaining 3.

2 of the remaining 3 are on Kennecott property, and will require getting permission. (I hear this is a tedious and difficult process.) The 3rd, Grandview Peak (not to be confused with Grandeur Peak) is just a really long, tedious access, for an (allegedly) unspectacular peak. I’ll get around to it…

2 of the remaining 3 are on Kennecott property, and will require getting permission. (I hear this is a tedious and difficult process.) The 3rd, Grandview Peak (not to be confused with Grandeur Peak) is just a really long, tedious access, for an (allegedly) unspectacular peak. I’ll get around to it…

I like to keep multi-year projects like this in the back of my head. They give me something to dream about. Me, my truck, my boots, a daypack, and one week. Just one week, and I can make the Sierra connection.

I like to keep multi-year projects like this in the back of my head. They give me something to dream about. Me, my truck, my boots, a daypack, and one week. Just one week, and I can make the Sierra connection.