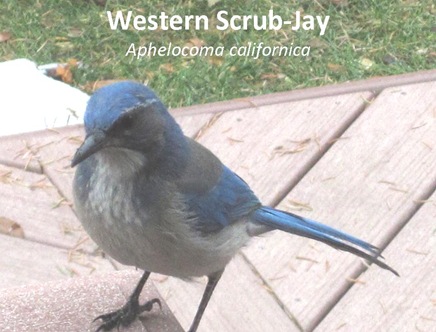

Since the new year I’ve been home a bit more often during the day, seeing as… well, I’ll get to that in the next post, which has given me an opportunity to see the comings and goings of various creatures in the yard- mainly birds- during the day. Last week one morning this big Scrub-Jay showed up on our deck.

The Western Scrub-Jay, Aphelocoma californica, is a super-easy bird to ID, as it’s pretty much the only blue bird in Salt Lake Valley in the winter. It has a distinctive call, arguably the harshest of corvid squawks: a razor-sharp, scratchy, climbing note that instantly catches your attention. When it shows up in the yard- never staying more than 5 or 10 minutes- it immediately disrupts the social equilibrium around the feeders*, sending juncos, siskins and finches scattering.

*I described the Winter “regulars” at my feeders 2 years ago in Bird Feeder Week. Man, was that a great week or what?

Scrub-Jays are birds of woodlands. In Utah they’re most often found in either Piñon-Juniper or Scrub Oak. This time of year you’ll almost always come across a couple if you go poking around on any of the foothill trails across the street form the zoo, or up around the Death Climb. Aphelocoma, the Scrub-Jays, includes 5 species, all native to North America, but the only other one* you’re likely to see in the US is the Florida Scrub-Jay, A. coerulescnes, native to, yes that’s right, Florida.

*The Island Scrub Jay, A. insularis, is endemic to Santa Cruz Island off the California coast.

The Western Scrub-Jay is divided up into a whole bunch of subspecies, grouped broadly within 2 clades, (which may in turn get reclassified as 2 distinct species sometime in the near future): one inland and one in California.

Side Note: This might sound similar in some ways to the division between Black-billed and Yellow-billed Magpies; the Sierra Nevada/Great Basin constitute a formidable barrier to migration. But while Magpies came over from Asia some 3-4 million years ago, Scrub-Jays are “New World Jays”, thought to have migrated Northward from Central America.

One of the interesting markers of A. californica subspecies is bill morphology. Subspecies that live in Piñon-Juniper woodlands have straight, thin bills for reaching in between cones scales to grab Piñon seeds, while those that live around Oak woodlands have slightly broader, more hooked beaks (better for working with acorns). Our subspecies here in Northern Utah, A. californica woodhouseii woodhouseii (sometimes called Woodhouse’s Scrub-Jay by bird geeks) has sort of an in-betweeener beak: straight but heavy, with a slight hint of a hook at the tip.

Side Note: An interesting corollary to these figures is the role- or rather lack thereof- played by Scrub-Jays in the modern-day distribution of Piñon pines*.

*I’ve covered Piñons extensively in this project, most notably in this post and this post. Man it is like I have a post for everything.

Stellers Jay’s loaded flight range is also pretty modest. It’s a bird of higher altitudes, and an infrequent visitor to Piñon-Juniper Woodland. When it does collect piñon nuts, it most often caches them at higher altitudes, unsuitable to piñon growth. But as temperatures rose following the end of the last ice age, its slightly-too-high seed caches may possibly have helped piñon expand up-slope within ranges where it was already established.

Scrub-Jays’ bills aren’t strong enough to pry apart the scales of unopened piñon cones. Instead they pick seeds from already opened cones, or wait for other, stronger-beaked corvids, such as Pinyon Jays, to open them for them, whereupon they harass them, drive them away, and make off with the goods.

What Scrub-Jays have going for them is their big brains. We covered the high intelligence of corvids when we looked at Magpies last Fall. Scrub Jays aren’t champion tool-makers, aren’t known to recognize themselves in mirrors, and certainly don’t display the phenomenal memory and navigational skills of Clark’s Nutcracker. But they appear to have both strong episodic memory and exceptional social awareness.

Episodic memory is the memory of autobiographical events and context, including time, place and emotion. In experiments Scrub-Jays have been placed in 2 different cages- one in which they were fed, the other in which they weren’t. Later the same jays were given the access to, and the opportunity to cache food items in, both cages. They overwhelmingly cached food in the cage in which they’d been hungry.

Extra Detail: Episodic memory is one of the 2 forms of declarative memory, which I described in this post. The other form of declarative memory is semantic memory, which is information or knowledge independent of personal context or relevance.

Scrub-Jays remember not only events, but others present at those events. When Scrub-Jays cache food items in front of other Scrub-Jays, they’ll frequently return later and move the items multiple times to avoid pilferage. They even appear to be able to keep track of specifically which individual birds saw them cache at which location on which occasion. Clark’s Nutcrackers, on the other hand, as brilliant as they are navigationally, seem to be utterly clueless to potential theft, happily caching away in front of Scrub-Jays and other thieving corvids.

Side Note: Lest this post make Scrub-Jays sounds like scoundrels, I should mention that they exhibit strong pair-bonding and parenting habits. In fact, when Scrub-Jays cache in front of their “spouse”, they only re-cache about as often as if they’d done so unobserved; their spouse is clearly on the same “team.”

Florida Scrub-Jays BTW, seem to take social cooperation even further, with young adults helping parents to cooperatively raise younger siblings. Family members also collaborate to take regular “watches” looking out for hawks, snakes and other predators. Similar cooperative breeding efforts are displayed by Western Scrub-Jays down in Mexico, but not here in the Western US.

But what’s interesting about this re-caching behavior is that it’s exhibited only by Scrub-Jays who have experienced cache-theft directly. By which you probably think I mean that once they’ve been robbed, they figure it out, smarten up and start caching in private or re-caching if they cached while observed by other Scrub-Jays, right? Wrong. What I meant was specifically the opposite: Scrub-Jays don’t re-cache until they themselves have robbed other birds’ caches. The experience of having observed another bird caching, and then they themselves having robbed that cache, clues them in that other Scrub-Jays watching them will likely figure out the same schtick. This learning-process suggests that Scrub-Jays, like us, have evolved a “theory of mind”- the ability to attribute knowledge, intent and desire to others. What does so-and-so know? What is he or she likely to do with that information?

Side Note: Autistic kids over age 4 usually still fail this test, which backs up my previously-expressed Half-Baked Theory that Clark’s Nutcracker is essentially an autistic corvid.

This social intelligence makes possible all sorts of deception. Scrub-Jays and other corvids, such as crows and ravens, routinely move caches, make false caches, and cache inedible items to throw off would-be thieves and competitors. In other words, they-deliberately and with forethought- lie. How “human” is that?

You may object that simply misleading is not lying, that a lie is a specific statement of falsehood, and corvids lack the level of language to be able to explicitly state such falsehoods. But I disagree; I’ve always felt that the nature of a lie is in intent, not words. Most of us are uncomfortable directly stating a falsehood, but we all “tell” little partial lies of omission all the time. When we host a party, we don’t call or email our friends whom we’re not inviting to tell them of the event. In business we don’t notify our competitors before calling on their clients, and we don’t usually tell our bosses before interviewing for another job. Often these lies of omission are harmless. Sometimes, as in the case of the uninvited guest, we tell ourselves it’s for the benefit of the person to whom we are “lying” (although the real reason is just as likely to be our own cowardice or conflict-avoidance…) Then there are lies of omission that might- or might not- cause harm, such as when your new boss fails to volunteer why the 2 people to hold your job before you quit, or when a manufacturer fails to disclose certain product information…

Part of being an intelligent social animal with a well-developed “theory of mind” is constantly deciding what information to share when with which individuals. To simply describe this information we share as “truths” or “lies”, while comforting, doesn’t always describe things the way they really are.

All of which brings me, in a rambling and roundabout way, to my point, which is this: there’s a piece of information, an aspect of this project, which, while I haven’t misstated or misrepresented, I haven’t been entirely forthright with you about, and it is this “lie of omission” about which I will come clean in the next post.

Next Up: ABC in Perseus.

Note About Sources: Thanks to my friend and fellow nature-blogger KB for help accessing several of the sources for this post. Scrub-Jay caching, pilfering and memory info came from Food Caching Western Scrub-Jays Keep Track of Who Was Watching When, Joanna Dally et al, Social cognition by food-caching corvids: the western scrub-jay as a natural psychologist, Nicola S. Clayton et al, The Mentality of Crows, Convergent Evolution of Intelligence in Corvids and Apes, Nathan J. Emery et al, and The rationality of animal memory: Complex caching strategies of western scrub jays, Nicola S. Clayton et al. General info on Scrub-Jays came from Kaufman Field Guide to Birds of North America, the Cornell University Lab of Ornithology All About Birds website and Wikipedia. Info on episodic memory and theory of mind (including the example story) came from Wikipedia. Figures on flight loads, speeds and ranges of various pine birds came from Made For Each Other: A Symbiosis of Birds and Pines, Ronald M. Lanner, and info on the historic range expansion of Piñon pine came from The Desert’s Past: A Natural Prehistory of the Great Basin, Donald K. Grayson.

5 comments:

Great post about Jays. I remember camping with my family as kid in various places in Southern California and one of our favorite things to do was watch the Stellers Jays. They were always so noisy, active, and interesting to observe, and we loved their "Mohawk" look.

Congrats on the 401st post! I would have congratulated you on the 400th but I was too late in reading the last one. Besides, 401reminds of Tr 401 in Crested Butte.

The Scrub Jays are pretty cool but your post brings up other questions. How much food they get from stealing (i.e what percentage of their overall food). Do the majority of them steal or only select Scrub Jays. What causes a Scrub Jay to steal for the first time (is it learned or inherent)? Do they feel bad after stealing or do they strike a victory pose?

Hmmm, what can your "lie of ommission" be? My guess - related to a post-retirement career? - is likely to be wrong so I'll guess I will have to tune into the same corvid time, same corvid channel to find out.

mtb w

Fascinating behavior.

El Gaucho- California does seem to have way more Stellers Jays than we do here in Utah. I always see tons of them in the summer in the forests around Tahoe.

mtb w- All great questions, none of which I can (yet) answer. Except the last one- see next post.

Scrub jays rock. We feed the same two or three birds (I think) peanuts from our back deck. They actually come when called. We find the peanuts stuffed into every nook and cranny in the yard. I will have to pay closer attention to who is re-caching in front of whom.

Post a Comment