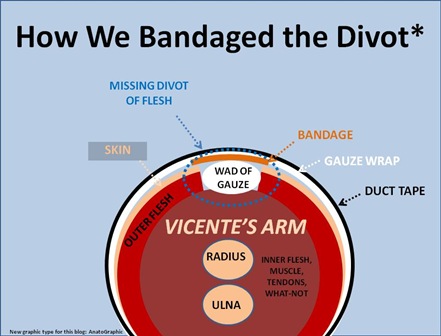

Catching sight of our expressions in each other’s faces, Hunky Neighbor and I snapped to and got to work. We needed to a) cover/patch the hole in Vicente’s arm, and b) get him someplace where we could get it stitched/repaired/filled/whatever-it-is-they-do-for-missing-divots-of-human-flesh.

Tangent: I just love starting multi-part posts this way- right in the thick of the action, like after a cliff-hanger episode. But mostly I like it because I imagine someone who hasn’t read the blog in a week or so checking in and being like, “Huh? Who? What? Hole in Vicente’s arm? OMG!- What happened??”

The Long-Awaited (And So Worthwhile) Third Tip

And it is now that I will reveal the Third- and far and away most valuable-  Tip: Ride with a 1st aid kit. I’m always amazed at how few mtn bikers do. Different riders have different philosophies as to what they carry when riding. Some prefer a minimalist approach, with just a couple of bottles and a CO2 cartridge in a jersey pocket. Others prefer a Camelbak with some tools, snacks, a pump, maybe a couple of spare parts and an extra layer of clothing. I won’t debate the merits of either approach here*, but both easily allow the inclusion of a minimalist 1st aid kit. Yes, minimalist, because when you get down to it, this is all you really need: Roll of Gauze, Tape**, and Something to Cut the Gauze With.*** My kit has a couple more odds & ends, the most useful of which has been a pair of tweezers.

Tip: Ride with a 1st aid kit. I’m always amazed at how few mtn bikers do. Different riders have different philosophies as to what they carry when riding. Some prefer a minimalist approach, with just a couple of bottles and a CO2 cartridge in a jersey pocket. Others prefer a Camelbak with some tools, snacks, a pump, maybe a couple of spare parts and an extra layer of clothing. I won’t debate the merits of either approach here*, but both easily allow the inclusion of a minimalist 1st aid kit. Yes, minimalist, because when you get down to it, this is all you really need: Roll of Gauze, Tape**, and Something to Cut the Gauze With.*** My kit has a couple more odds & ends, the most useful of which has been a pair of tweezers.

*No, I won’t debate them here. But I am curious, if any other hydration pack-using mtn bikers are reading this: It seems that I am (very) frequently loaning/giving water, food, tubes, patches, cables, duct tape, bandages, etc. to bottle-only mtn bikers. It is just me or is this your experience as well?

**This doesn’t need to be medical/1st aid-type tape; I carry short lengths of duct tape and electrical tape, both wrapped around my hand-pump.

***I actually carry a small knife, but that’s primarily so that I look bad-ass. Most multi-tools have a small cutting blade.

OCRick and I both had 1st aid kits, but neither of us had ever bandaged anything like The Divot before. Hunky Neighbor* and I conferred, and quickly decided on the following: 1) a rolled-up ball of gauze inserted into the divot**, 2) the remainder of the gauze roll wrapped around the arm/wad/divot, and 3) a length of duct tape once around to keep thing in place.

*Not a doctor, but is married to one.

**Yes, this was the grossest part.

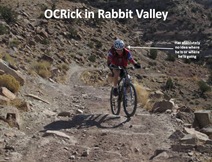

Vicente, remarkably, was calm and only in mild pain. We actively discouraged him from examining the wound, and I don’t believe he observed the structural/rotational aspect I described in the previous post. As we completed the bandage and re-packed our gear, something was bothering me. I snuck a furtive glance over my shoulder, casting a glance about for … something red. I looked again. No sign of it. We mounted up and started rolling back, taking a cut-off trail back toward the trailhead.

Vicente, remarkably, was calm and only in mild pain. We actively discouraged him from examining the wound, and I don’t believe he observed the structural/rotational aspect I described in the previous post. As we completed the bandage and re-packed our gear, something was bothering me. I snuck a furtive glance over my shoulder, casting a glance about for … something red. I looked again. No sign of it. We mounted up and started rolling back, taking a cut-off trail back toward the trailhead.

As we set out I admonished everyone to keep things mellow and to walk technical sections*. Pretty much everyone complied… except Vicente. He rolled 2 sections that made me hold my breath, including a rutted slope down into a gully that- I am not kidding- all the rest of us walked after him.

*So as not to encourage Vicente to ride them.

We made it back to the trailhead in less than 30 minutes and were driving shortly after. Hunky Neighbor googled a hospital on his iPhone (yes, he’s one of them) and then phoned in for directions. We made it there in about 15 minutes.

We made it back to the trailhead in less than 30 minutes and were driving shortly after. Hunky Neighbor googled a hospital on his iPhone (yes, he’s one of them) and then phoned in for directions. We made it there in about 15 minutes.

Fruita’s hospital is small but brand-spanking new. The staff is prompt, cheerful and courteous, and the waiting room was empty. Vicente was admitted in about 2 minutes.

In the waiting room the 4 of us twiddled our thumbs about and made chit-chat. Then one of us- I think it was Young Ian- asked, “Did any of you guys see it?” It quickly turned out that we’d all looked for it- The Divot- while pretending not to- but none of us had spotted it.

In the waiting room the 4 of us twiddled our thumbs about and made chit-chat. Then one of us- I think it was Young Ian- asked, “Did any of you guys see it?” It quickly turned out that we’d all looked for it- The Divot- while pretending not to- but none of us had spotted it.

“Where could it have gone?” we all asked. Everything within 30 feet was brown, olive or tan; you would think a 1” x 1.5” chunk of bloody red flesh would show up… But none of us had spotted it. We all sort of shrugged and mumbled a bit more, somehow resigned but uneasy that we’d left an actual piece of our comrade out in the desert.

Vicente emerged in about 45 minutes with bandaged arm, knee, a dozen or so staples (which we couldn’t see) and prescriptions for codeine and antibiotics. He was smiling and we all laughed and walked back outside and… into the rain.

Our standard Guys Trip Weekend Plan is to ride during the day Saturday and Sunday, and also night-ride Saturday night. This is particularly important in the Fall when daylight is limited, because otherwise you’re looking at a LONG time around the campfire… But night-riding in the rain is just too much of a downer. We hemmed and hawed a bit, went by the drugstore to fill Vicente’s prescriptions, and then killed more time eating dinner in town. After dinner it was still spitting a bit, so we decided to head on over to the Kokopelli trailhead and see if the weather would let up.

We arrived just as darkness was setting in and the lot was emptying out. There were some picnic tables under an awning nearby and we went over to kill some more time and take shelter from the rain. I walked over, my headlamp lighting the way on a dark, rainy, spooky night. I’m fairly tall, about 6’2”, and the edge of the awning was only about a foot or so above my head. As I approached the awning, at the very last minute, my headlamp lit up, about 8” in from of my face- this:

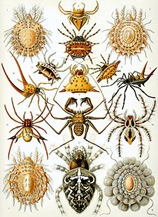

Spiders are way cool when you spot them walking around on the ground in broad daylight. When you practically bump your face into them on a rainy night, they can give you bit of a start.

Spiders are way cool when you spot them walking around on the ground in broad daylight. When you practically bump your face into them on a rainy night, they can give you bit of a start.

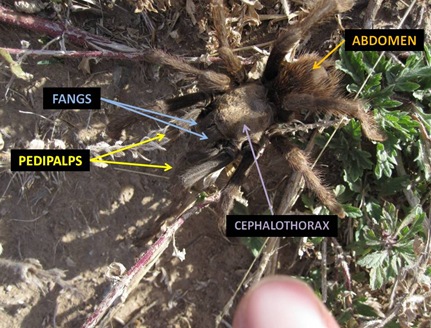

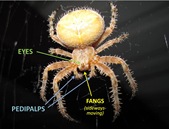

Thanks to last week’s tarantula encounter out in the Oquirrhs, we already know a bit about spiders and their anatomy. But one of the things we didn’t talk about is the incredible diversity of spiders.  There are something like 40,000 species worldwide, and what’s cool about this spider is that when compared and contrasted last week’s tarantula it really showcases the diversity and breadth across the order Araneae. This gal- a Cat-Faced Spider, Araneus gemmoides*, hasn’t shared a common ancestor with a tarantula in over 200 million years- longer ago than when we last shared a common ancestor with kangaroos! It’s called “Cat-Faced” BTW, because the design on the top of the abdomen is thought to resemble the face of a cat. It’s sometimes also known as a “Jewel Spider.”

There are something like 40,000 species worldwide, and what’s cool about this spider is that when compared and contrasted last week’s tarantula it really showcases the diversity and breadth across the order Araneae. This gal- a Cat-Faced Spider, Araneus gemmoides*, hasn’t shared a common ancestor with a tarantula in over 200 million years- longer ago than when we last shared a common ancestor with kangaroos! It’s called “Cat-Faced” BTW, because the design on the top of the abdomen is thought to resemble the face of a cat. It’s sometimes also known as a “Jewel Spider.”

*Special thanks to Andrew over at BugGuide.Net for his help on the ID. What a wonderful site.

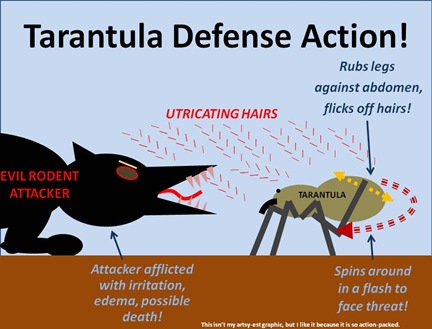

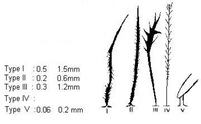

A tarantula is in many ways considered a “primitive” spider, in that it exhibits many of the supposed characteristics of very ancient spiders. Its fangs for example, move up and down, and its only webs are those lining its burrows or those used by the males to deposit sperm packets upon*. Since then, spiders have evolved the sideways-moving fangs common to most of the world’s spiders, and the ability to spin a variety of sophisticated web types, including Funnel webs, Dome webs, Sheet webs, Tubular webs, Tangle webs, and the type of web most of us think of when we think, “Spiderweb”, the Orb web. The Cat-Faced Spider is an Orb-Weaver, with sideways-moving fangs.

*Actually called “sperm-mats.” Yes, really. That’s what they’re called.

Spiderwebs

At least once a month in this project, I stumble across a topic where, once I get into it, I suddenly think, “Wow! I could do a whole blog on this!”  Spiderwebs is one of those “wow” topics. Overwhelmingly, a given species of spider spins a specific type of web. Traditionally spiderwebs have been viewed in terms of 5 stages of complexity and sophistication, with stage 1 basically a trip-line or two in front of a hole, while stage 5 is a full-blown orb web. It was generally thought that each of these stages evolved from the previous stage, which in turn led to all sorts of fascinating examples of very distantly-related spiders having evolved very similar web designs. But now some researchers believe that orb webs have been around far longer than originally thought, and that other, apparently “less sophisticated” web designs may have evolved from orb webs. In this “monophyletic” view of orb-weaving, orb webs may signal an ancient and common ancestry between distantly-related species. The whole topic is unsettled, complicated and absolutely fascinating.

Spiderwebs is one of those “wow” topics. Overwhelmingly, a given species of spider spins a specific type of web. Traditionally spiderwebs have been viewed in terms of 5 stages of complexity and sophistication, with stage 1 basically a trip-line or two in front of a hole, while stage 5 is a full-blown orb web. It was generally thought that each of these stages evolved from the previous stage, which in turn led to all sorts of fascinating examples of very distantly-related spiders having evolved very similar web designs. But now some researchers believe that orb webs have been around far longer than originally thought, and that other, apparently “less sophisticated” web designs may have evolved from orb webs. In this “monophyletic” view of orb-weaving, orb webs may signal an ancient and common ancestry between distantly-related species. The whole topic is unsettled, complicated and absolutely fascinating.

Side Note: Part of the problem is that neither spiders nor spiderwebs fossilize particularly well.

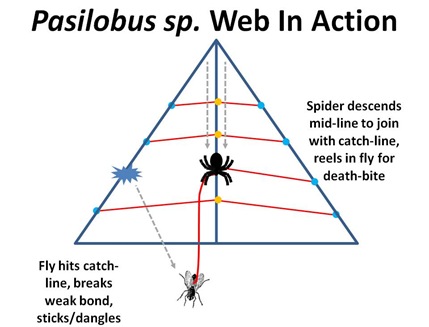

Arachno-Tangent #1: Just to give you a taste of the amazing variety of web-types, here’s the Coolest Spiderweb Ever. New Guinean spiders of the genus Pasilobus build triangular webs. The triangle is bisected by a single strand, called the mid-line. Then the mid-line is joined to the sides of the triangle by between 4 and 11 pairs of lines. These “catch-lines” are the only sticky strands in the web.

Now these catch-lines- and here’s the cool part- are connected to the mid-line by very strong bonds, but to the sides of the triangle by very weak bonds. So when a fly hits the catch-line, it breaks off on the outside, and then the fly is left hanging from the broken-off catch-line.

Now these catch-lines- and here’s the cool part- are connected to the mid-line by very strong bonds, but to the sides of the triangle by very weak bonds. So when a fly hits the catch-line, it breaks off on the outside, and then the fly is left hanging from the broken-off catch-line.

The spider then scoots down the mid-line to where it connects with the broken-off catch-line, reels in the catch-line and bites the fly. How cool is that?

The spider then scoots down the mid-line to where it connects with the broken-off catch-line, reels in the catch-line and bites the fly. How cool is that?

All About Orb Webs

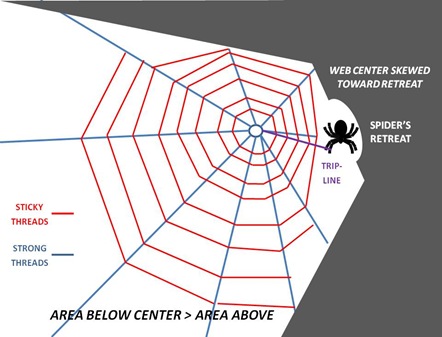

Regardless of how orb webs evolved, they work very well. Like nearly all spiderwebs, they’re generally vertical. Vertical webs are likelier to catch a flying insect (insects spend most flight time moving horizontally) and retain struggling insects (if an insect frees itself from a given strand, it tends to fall down.) Orb webs utilize 2 very different types of threads. The first are strong, non-sticky threads which provide the overall strength and structure of the web, and along which the spider can move rapidly. In most orb webs these are the radial threads, or the “spokes”. The second type are the sticky threads between the spokes, which ensnare passing insects through adhesion or entanglement.

Due to the spoke-like nature of the radial threads, the spacing between sticky lines becomes greater the further one gets from the center.

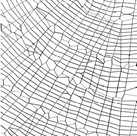

Arachno-Tangent #2: Spiders of the genus Nephila have evolved a neat solution to this problem. As they spin the web outwards from the center, they periodically “re-spoke” the wheel of the web to increase the density of radial lines as seen in this graphic (not mine*.)

Arachno-Tangent #2: Spiders of the genus Nephila have evolved a neat solution to this problem. As they spin the web outwards from the center, they periodically “re-spoke” the wheel of the web to increase the density of radial lines as seen in this graphic (not mine*.)

*BTW, if you’re interested, the paper from which I pulled this graphic makes a strong (and very readable) case for the polyphyletic view, that orb webs have evolved independently multiple times.

Now, here’s the really cool thing: I came across this tidbit while researching spiderwebs for this post. And I thought, “Nephila… Nephila…. Where have I come across that before?” And then I remembered: The Golden Orb Spider that we saw back in March down in Costa Rica and about which I posted in the Creepy Crawly Post.

So I went back and checked my old photos, and sure enough, you can make out the “re-spoking” in the web. Wow.

Moral of the tangent: save your vacation pics!

Moral of the tangent: save your vacation pics!

Most orb webs are asymmetrical, rather than a perfect circle, and the “stretched”/bigger part of the web is almost always the lower half. The reason for this is that once an insect has hit the web, the spider needs to reach and bite it quickly before it escapes, and spiders can move down across a web much more quickly than they can move up it.

There’s another common reason for web asymmetry; the logical place for an orb-weaving spider to hang out- in terms of access to all parts of the web- is in the center. But center placement can make the spider visible to passing insects, and in fact this is why many spiders only hang out in the web-center at night. During the day many spiders stay in a “retreat” off the periphery of the web, which is connected to the web-center by a “trip-line.” But since the spider must travel first from its retreat to the web-center before proceeding to the prey location along the nearest radial line, it makes sense to place the center as closely as possible to the retreat.

There’s another common reason for web asymmetry; the logical place for an orb-weaving spider to hang out- in terms of access to all parts of the web- is in the center. But center placement can make the spider visible to passing insects, and in fact this is why many spiders only hang out in the web-center at night. During the day many spiders stay in a “retreat” off the periphery of the web, which is connected to the web-center by a “trip-line.” But since the spider must travel first from its retreat to the web-center before proceeding to the prey location along the nearest radial line, it makes sense to place the center as closely as possible to the retreat.

The Cat-Faced Spider is the largest orb-weaver in the Western US. The irony with spiders in general of course is that size in no way corresponds to danger to humans, and this is absolutely the case with A. gemmoides.  It avoids people, hardly ever bites them, and when it does is about as bad as a bee or wasp sting. The big ones you see in the webs are always females (males are much smaller) and you almost always see them in late Summer or early Fall. The reason for this is the same reason you don’t notice Sunflowers until late summer- they’re “annuals”. They hatch in the Spring, grow throughout the summer, and mate in the Fall. Females lay a single egg-case, and then die a few days later. Cat-Faced Spiders never encounter either their parents or their offspring. This in contrast, BTW, to tarantulas, which live for years or even decades.

It avoids people, hardly ever bites them, and when it does is about as bad as a bee or wasp sting. The big ones you see in the webs are always females (males are much smaller) and you almost always see them in late Summer or early Fall. The reason for this is the same reason you don’t notice Sunflowers until late summer- they’re “annuals”. They hatch in the Spring, grow throughout the summer, and mate in the Fall. Females lay a single egg-case, and then die a few days later. Cat-Faced Spiders never encounter either their parents or their offspring. This in contrast, BTW, to tarantulas, which live for years or even decades.

The spiderlings scatter by “ballooning”, and the few that survive often take up residence by awnings and eaves in and around human habitation. A. gemmoides- lie pigeons, dandelions and brown-headed cowbirds- is one of those creatures that has benefitted from human settlement, and in fact they appear to have adapted to human habitation to the extent that they favor web-sites near lights, as they attract passing insects in the evening.

The spiderlings scatter by “ballooning”, and the few that survive often take up residence by awnings and eaves in and around human habitation. A. gemmoides- lie pigeons, dandelions and brown-headed cowbirds- is one of those creatures that has benefitted from human settlement, and in fact they appear to have adapted to human habitation to the extent that they favor web-sites near lights, as they attract passing insects in the evening.

So scary-looking as they may be, Cat-Faced Spiders are pretty much harmless and eat lots of bugs. Leave them alone when you find them.

We killed time, with some minor bike maintenance until it was fully dark and the rain petered out. It hadn’t been enough to soak the trails and so we ventured out for our night-ride.  We rode Rustler Trail, a beginner loop by day, but a thrilling, smooth, fast, twisty roller-coaster of a ride on a cloudy, moonless night. We liked it so much we did a second lap, which Vicente sat out, as his anesthetic was wearing off. (Video kind of lame, but none of the night-ride photos turned out. No really, here’s what they all looked like, right.)

We rode Rustler Trail, a beginner loop by day, but a thrilling, smooth, fast, twisty roller-coaster of a ride on a cloudy, moonless night. We liked it so much we did a second lap, which Vicente sat out, as his anesthetic was wearing off. (Video kind of lame, but none of the night-ride photos turned out. No really, here’s what they all looked like, right.)

Following the ride we returned to Rabbit Valley to camp for a 2nd night. The sky was dark and forbidding, but the rain held off. Tired from a long day, we sat by the fire or a bit and called it a night.

Later, much later, I awoke. The sky was still partly cloudy, with just a few stars peeking out in Perseus and Cassiopeia. Something was nagging me. My mind wandered for a bit before locking onto it: Somewhere out in the desert right now, a small nocturnal rodent had found a delectable meaty morsel. Seizing it hungrily in her jaws, she scuttled back to her burrow to share the treasure with her brood, and together they feasted… feasted on a divot of human flesh!

Happy Halloween!

Post-script: On a serious note, I wish this were the end of the Halloween tale, but it’s not. Returning to Salt Lake, Vicente’s wound became infected with antibiotic-resistant bacteria. On Tuesday a surgeon reopened the wound to clean it and remove additional debris, and in so doing had to make 2 additional incisions, each 3+ inches in length. He left the wound open for a couple of days and put Vicente on stronger, intravenous antibiotics. Today Vicente returns to the surgeon, hopefully to close the wound. He’s scheduled to fly to Brazil tomorrow for a conference; he’ll know today if that’s still the plan. Wish him luck.