Note: Wow, this post has it all: botany, entomology, a death-defying-killer-bee-escape-story, an extended work-related tangent and one of my best graphics yet- no matter why you read this blog, this post has something for you!

So yeah, bees. Last September I blogged about my friend Spence, the beekeeper, and how I helped him harvest honey and got all amped up to keep bees. Well, I didn’t do it this year. Too much going on, too busy, blah, blah, you don’t care anyway so I won’t make excuses. But here’s the cool thing- my friend Bev did get new bees, and this past weekend Bird Whisperer and I went over to her place to help introduce her newly arrived bees to their new hive.

Obligatory Botanical Travel Spotlight

So, as I alluded to in the comments to Monday’s post, I had to travel this week, specifically to a trade show. And… oh no, I feel it coming on- a trade-show tangent!

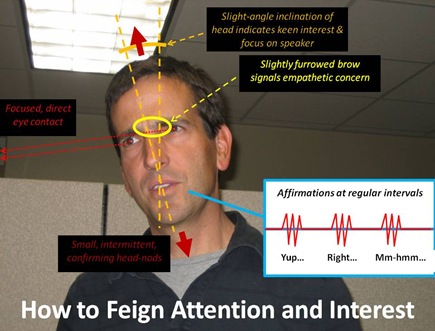

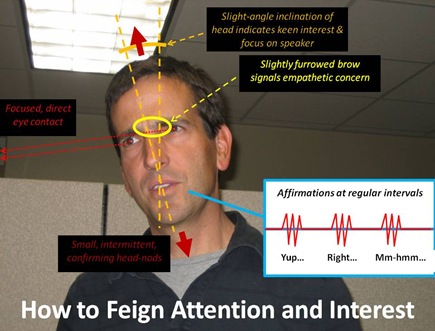

Trade Show Tangent: As longtime readers know, I earn a living in technology sales. Over the years, this has involved, from time to time, manning a booth at a trade show, a task I loathe. I hate accosting people in the hallway and pitching them and scanning their badge (even though I’m very good at it.) I hate smiling and saying, “Hi, how’s it going?” to strangers all day (even though- again- I’m very good at it.) I hate nodding and saying, “Mm-hmm, yup, right, uh-huh…” repeatedly as they describe some techie IT project to me in excruciating detail in order to appear that I have the slightest idea what it is they’re talking about. I do this last part really well. I look real serious- as if whatever the hell they’re working on is of critical importance*. I furrow my brow slightly- not enough to look angry- but just enough to look concerned that they are facing whatever challenge they are facing. I tilt my head to the side just a tiny bit- maybe 5 or 10 degrees- to accentuate the intensity of my interest and attention. And at regular 5-7 second intervals I mumble positive affirmations: “Mm-hmm… yup… right… uh-huh… exactly… I see…”

Trade Show Tangent: As longtime readers know, I earn a living in technology sales. Over the years, this has involved, from time to time, manning a booth at a trade show, a task I loathe. I hate accosting people in the hallway and pitching them and scanning their badge (even though I’m very good at it.) I hate smiling and saying, “Hi, how’s it going?” to strangers all day (even though- again- I’m very good at it.) I hate nodding and saying, “Mm-hmm, yup, right, uh-huh…” repeatedly as they describe some techie IT project to me in excruciating detail in order to appear that I have the slightest idea what it is they’re talking about. I do this last part really well. I look real serious- as if whatever the hell they’re working on is of critical importance*. I furrow my brow slightly- not enough to look angry- but just enough to look concerned that they are facing whatever challenge they are facing. I tilt my head to the side just a tiny bit- maybe 5 or 10 degrees- to accentuate the intensity of my interest and attention. And at regular 5-7 second intervals I mumble positive affirmations: “Mm-hmm… yup… right… uh-huh… exactly… I see…”

*It almost never is. 99% of corporate IT initiatives Never Go Anywhere.

There are of course about a million things to make fun of at technology trade shows, but my favorite is the droves of attendees who sit in the “mini-auditoriums” of the larger vendor-booths* to hear a 10-15 minute PowerPoint sales presentation, for which they will be rewarded with… a T-shirt.

There are of course about a million things to make fun of at technology trade shows, but my favorite is the droves of attendees who sit in the “mini-auditoriums” of the larger vendor-booths* to hear a 10-15 minute PowerPoint sales presentation, for which they will be rewarded with… a T-shirt.  Seriously, here are all these 40 and 50 year-old guys, virtually all of whom make well over $100,000 a year, spending 15 minutes of their day listening to some pitch they couldn’t care less about so that they can get a T-shirt with the vendor’s name on it. I want to run over and say: “Hello! You can BUY a t-shirt at Target for like 4 bucks!” It’s really amazing- the minute these guys walk into the Moscone Center they turn into Virtual Homeless Vagrants, walking around, begging and collecting bags full of cheap garbage (pens, t-shirts, Frisbees, glowing mugs) which they then tote around for 3 days before presumably cramming them into their checked baggage for the flight back to Omaha or wherever.

Seriously, here are all these 40 and 50 year-old guys, virtually all of whom make well over $100,000 a year, spending 15 minutes of their day listening to some pitch they couldn’t care less about so that they can get a T-shirt with the vendor’s name on it. I want to run over and say: “Hello! You can BUY a t-shirt at Target for like 4 bucks!” It’s really amazing- the minute these guys walk into the Moscone Center they turn into Virtual Homeless Vagrants, walking around, begging and collecting bags full of cheap garbage (pens, t-shirts, Frisbees, glowing mugs) which they then tote around for 3 days before presumably cramming them into their checked baggage for the flight back to Omaha or wherever.

*Our company doesn’t have one of these large-type booths. We have one of the little 10’x10’ booths, which we cram full of brochures, displays and salespeople, making it reminiscent of one of the little tables at your kid’s science fair.

Yeah, so anyway, I was in San Francisco, and whenever I travel- particularly to California- I try to blog about some cool botany-thing. On this trip I was only in the airport and downtown SF, but I still saw something cool.

Next time you land at SFO, just before you land, look out the window to the left (pic left). All that grass you see along t he shoreline-wetlands is a kind of grass called cordgrass, which grows along shorelines and coastal marshes. The native cordgrass in the San Francisco Bay is California Cordgrass, Spartina foliosa, and it’s grown along the shores of the bay for millennia.

Next time you land at SFO, just before you land, look out the window to the left (pic left). All that grass you see along t he shoreline-wetlands is a kind of grass called cordgrass, which grows along shorelines and coastal marshes. The native cordgrass in the San Francisco Bay is California Cordgrass, Spartina foliosa, and it’s grown along the shores of the bay for millennia.

But here’s the weird thing: Back in the 70’s another species of cordgrass, Smooth Cordgrass, Spartina alterniflora (pic right), which is native to the East Coast, was deliberately introduced to the SF Bay (why, I don’t know.) And in the 30+ years since, it, and Smooth x California Cordgrass hybrids have practically taken over, almost completely replacing (or hybridizing with) the native California Cordgrass to the point that it’s been nearly eliminated from the SF Bay. Smooth Cordgrass and the Smooth x California hybrid are able to colonize mudflats at lower tidal levels than California Cordgrass, and so the replacement is significantly altering the shoreline of large parts of the bay. That’s an example of a plant introduction that has decimated a native plant- all in your lifetime- and you can see it anytime you land at SFO.

And in the 30+ years since, it, and Smooth x California Cordgrass hybrids have practically taken over, almost completely replacing (or hybridizing with) the native California Cordgrass to the point that it’s been nearly eliminated from the SF Bay. Smooth Cordgrass and the Smooth x California hybrid are able to colonize mudflats at lower tidal levels than California Cordgrass, and so the replacement is significantly altering the shoreline of large parts of the bay. That’s an example of a plant introduction that has decimated a native plant- all in your lifetime- and you can see it anytime you land at SFO.

Side Note: England has a similar but even cooler cordgrass-invasion story that also involves hybridization, polyploidy, C4 photosynthesis and a new species.

Back to Bev

So back to Bev. Bev is Awesome Wife’s longest and dearest friend in Utah. Bev is intelligent, kind, and the Craftiest Human Alive. I don’t mean “crafty” like Blofeld or Dick Cheney; I mean “crafty” as in “really, really good at crafts.” Bev takes on one project after another- a recent example was building a Koi Fish pond in her back yard- and consistently nails them. So when Bev decided to take on bee-keeping- constructing and hand-painting her own hive, I knew that I would be able to “assist” her, thereby gaining the fun and experience of bee-keeping, without, uh, actually having to do anything.

In the morning, Bev had picked up her bees and queen at Jones Bee, and later in the day, when the sun was low, we set about introducing them to their new hive. In this pic you can the bees as Bev picked them up; the queen sits in a can that is concealed by the swarm. We squirted them down with sugar water to calm and distract them, then removed the queen from the box via an opening at the top of the box (concealed by white board in photo.)

In the morning, Bev had picked up her bees and queen at Jones Bee, and later in the day, when the sun was low, we set about introducing them to their new hive. In this pic you can the bees as Bev picked them up; the queen sits in a can that is concealed by the swarm. We squirted them down with sugar water to calm and distract them, then removed the queen from the box via an opening at the top of the box (concealed by white board in photo.)  The queen is delivered in the special teeny-tiny screened box you see in the pic left, one end of which has an opening that Bev plugged with a mini-marshmallow. Over the next few days, the workers will chew their way through the marshmallow to her; by the time they reach her, they’ll be accustomed to her smell and won’t kill her.

The queen is delivered in the special teeny-tiny screened box you see in the pic left, one end of which has an opening that Bev plugged with a mini-marshmallow. Over the next few days, the workers will chew their way through the marshmallow to her; by the time they reach her, they’ll be accustomed to her smell and won’t kill her.

We placed the little queen box on a tiny hangers (2 nails) between 2 of the frames before introducing the swarm, which Bev accomplished by dumping the box upside-down, then gently shaking the remaining bees out. (pic right) The whole process went super-smoothly; no one was stung, and the vast majority of the bees wound up in the hive.

We placed the little queen box on a tiny hangers (2 nails) between 2 of the frames before introducing the swarm, which Bev accomplished by dumping the box upside-down, then gently shaking the remaining bees out. (pic right) The whole process went super-smoothly; no one was stung, and the vast majority of the bees wound up in the hive.

Bev’s bees are a subspecies of Honeybee known as “Italians”, specifically Apis mellifera ligustica, which are known for their gentle demeanor, and for which they are a favorite of first-time beekeepers. Certainly they were the mellowest bees I’ve ever been around. And I’ve been around a few bees.

Bev’s bees are a subspecies of Honeybee known as “Italians”, specifically Apis mellifera ligustica, which are known for their gentle demeanor, and for which they are a favorite of first-time beekeepers. Certainly they were the mellowest bees I’ve ever been around. And I’ve been around a few bees.

My Death-Defying Killer Bee Attack Story

OK, so first of all, I’m not actually sure they were killer bees, but I said so in the title because a) they were really aggressive, b) they well could have been an “Africanized”, as are many wild swarms in the Mojave, and c) it makes a way better story. Anyway, the story is this.

Quick Tangent About Africanized/Killer Bees: The African subspecies of Honeybee, A. melliferra scutellata is significantly more aggressive than the various European subspecies. In 1957 a Brazilian entomologist was conducting hybridization experiments between African and European honeybees, seeking a more productive strain. In the course of the work, 26 African queens escaped, some number of which mated with local Honeybee drones and reproduced. Over the following decades they expanded and hybridized their way northward, crossing the Brazilian border around 1970, reaching the US border in 1990, and appearing in Clark County, Nevada in 1996. Fortunately (for most of us) they don’t tolerate cold winters, and their Northward progress has largely halted, but they’re not uncommon in Southern Nevada.

In 1957 a Brazilian entomologist was conducting hybridization experiments between African and European honeybees, seeking a more productive strain. In the course of the work, 26 African queens escaped, some number of which mated with local Honeybee drones and reproduced. Over the following decades they expanded and hybridized their way northward, crossing the Brazilian border around 1970, reaching the US border in 1990, and appearing in Clark County, Nevada in 1996. Fortunately (for most of us) they don’t tolerate cold winters, and their Northward progress has largely halted, but they’re not uncommon in Southern Nevada.

Africanized or “Killer” Bees aren’t anymore venomous than “regular bees; they’re just more aggressive. It usually takes ~500+ stings to kill a healthy (non-allergic) adult human, but sometimes as few at 100 or so will do the trick.

Africanized or “Killer” Bees aren’t anymore venomous than “regular bees; they’re just more aggressive. It usually takes ~500+ stings to kill a healthy (non-allergic) adult human, but sometimes as few at 100 or so will do the trick.

In October 2004 I climbed Virgin Peak in Nevada, south of Mesquite (in Clark County.) I’d gazed upon the peak many times from the West Rim of Little Creek Mountain, and finally got around to climbing it.

Side Note: The other peak I’d gazed up upon from Little Creek- Moapa Peak- I’d already climbed 3 years earlier. Moapa is the huge peak on the North side of I-15 between Mesquite and Las Vegas, and it is an absolutely spectacular and thrilling climb which features hair-raising exposure and Desert Bighorn Sheep. It’s also a bit hazardous, so if you do it, do it with a friend. (So not like I did it.)

Accessing the peak requires 2 hours of rough, tedious un-paved driving from Mesquite. I mention this because it meant that at the “trailhead”, I was 2 hours from help, and almost 3 hours from a hospital. Before I left my vehicle, I left a sunshower (solar-heated shower) on the hood, so that I could wash up when I returned, before the ~8 hour drive home.

Accessing the peak requires 2 hours of rough, tedious un-paved driving from Mesquite. I mention this because it meant that at the “trailhead”, I was 2 hours from help, and almost 3 hours from a hospital. Before I left my vehicle, I left a sunshower (solar-heated shower) on the hood, so that I could wash up when I returned, before the ~8 hour drive home.

The climb was all off-trail but enjoyable and fairly easy (way easier than Moapa.) Virgin Peak gets climbed only about 3-4 times/year and offers spectacular views. When I returned to the truck a few hours later, I took off my pack, had a cold drink, dug out clean shorts and a t-shirt and walked over to the hood, where there were a couple of bees buzzing around the shower, attracted by the glint of water. I picked up the shower to place it on top of the truck and- YEEEAAAARGH!!!- there were probably a hundred+ bees swarming under the sunshower! I quickly dropped the shower and jumped back.

Now, at this point, the logical action would have been to forget the shower- which cost ~$20 at REI- get the truck and drive home. But you have to understand- I really wanted a shower. So I dithered and waffled for a few minutes trying to think of a way to get rid of the bees. And the plan I came up with was so dumb, so lame, and so completely retarded that I am embarrassed to share it.

Now, at this point, the logical action would have been to forget the shower- which cost ~$20 at REI- get the truck and drive home. But you have to understand- I really wanted a shower. So I dithered and waffled for a few minutes trying to think of a way to get rid of the bees. And the plan I came up with was so dumb, so lame, and so completely retarded that I am embarrassed to share it.

I figured that I would start driving down the “road” (really a rock-strewn dry wash) with the sunshower in place on the hood, and the shaking/driving of the car would make the bees just fly off. Of course, that is not what happened.

As soon as I started driving, within 10 feet, the sunshower- which is basically a plastic bag full of water- rolled off the front of the truck. The bees immediately arose and spread in an angry, 3-dimensional 20-foot-radius sphere around the truck , and in a fraction of an instant I made the dumbest, craziest split-second decision ever: I yanked up the hand-brake, jumped out of the car, slamming the door behind me, and waving my arms maniacally around my head and screaming at the top of my lungs ran around the front of the truck, picked up the sunshower, ran with it to the passenger side, opened the door, threw the sunshower inside and slammed the door. The door caught on the hose and bounced back open. Still screaming, I tucked the hose inside, slammed it again, and ran around the back of the truck, opened the driver’s side door, jumped in and slammed the door behind me.

I immediately turned my head to the left and saw that at least a dozen+ bees were flinging themselves against the window, trying to get at me. Other bees were landing on the hood in front of me and arching their abdomens, trying to sting the vehicle. Amazingly not a single bee stung me nor got inside the vehicle. The crazed bees continued to swarm and “attack” the truck for a full half-mile down the rough road.

I immediately turned my head to the left and saw that at least a dozen+ bees were flinging themselves against the window, trying to get at me. Other bees were landing on the hood in front of me and arching their abdomens, trying to sting the vehicle. Amazingly not a single bee stung me nor got inside the vehicle. The crazed bees continued to swarm and “attack” the truck for a full half-mile down the rough road.

Moral of the story: I am both phenomenally dumb and extraordinarily lucky.

Back to Bev’s Bees. Bev’s prepared for her new hobby well, reading the Beekeeping For Dummies cover to cover. She’s going to pay special attention to the hive over the next few weeks as they get accustomed to the queen and settle into their new home. And over the coming year, she’ll keep an eye out for a number of things that can go wrong.

Bee Genes

Unless you’ve spent the last several years in a cave, you probably heard that a few years back geneticists mapped the human genome*. But what you probably didn’t hear was that in 2006 they successfully mapped the Honeybee genome. And when scientists compared the Honeybee genome with the already-mapped genomes of other insects, such as the Fruit Fly and the Mosquito, they saw some interesting differences.

Unless you’ve spent the last several years in a cave, you probably heard that a few years back geneticists mapped the human genome*. But what you probably didn’t hear was that in 2006 they successfully mapped the Honeybee genome. And when scientists compared the Honeybee genome with the already-mapped genomes of other insects, such as the Fruit Fly and the Mosquito, they saw some interesting differences.

*Well, they mapped most of it. There are still problem areas- mainly centromeres, telomeres and some genes associated with immune response.

First, Honeybees have more genes related to learning. This isn’t surprising; they make a living by seeking out sources of pollen and nectar, communicating the location of those sources to their hive-mates, and are apparently able to distinguish between “same” and “different”.

Second, they have more genes related to smell, which again makes sense, given that bees navigate to flowers partly by scent.

Third, Honeybees seem to have significantly fewer genes associated with immune response, disease resistance and detoxification, which seems odd until you think about how they live. Honeybee hives are remarkably clean. Dedicated “nurse” bees continually clean waste, trash and dead bees/larvae etc. from the hive. Compared to a solitary insect, a social bee’s living environment is pretty darn healthy. So over millions of years, evolutionary pressure from disease on Honeybees has probably relaxed a bit. For a long time this has worked out generally well for bees, but in modern times, as human travel has enabled the rapid transport and dispersal of bees, parasites and diseases, Honeybees have encountered a number of new threats for which they’re genetically unprepared.

Third, Honeybees seem to have significantly fewer genes associated with immune response, disease resistance and detoxification, which seems odd until you think about how they live. Honeybee hives are remarkably clean. Dedicated “nurse” bees continually clean waste, trash and dead bees/larvae etc. from the hive. Compared to a solitary insect, a social bee’s living environment is pretty darn healthy. So over millions of years, evolutionary pressure from disease on Honeybees has probably relaxed a bit. For a long time this has worked out generally well for bees, but in modern times, as human travel has enabled the rapid transport and dispersal of bees, parasites and diseases, Honeybees have encountered a number of new threats for which they’re genetically unprepared.

One such threat is foulbrood (pic right), a bacterial disease that has possibly been made worse by overuse of antibiotics. Foulbrood attacks and kills bee larvae 3 days old or younger.

One such threat is foulbrood (pic right), a bacterial disease that has possibly been made worse by overuse of antibiotics. Foulbrood attacks and kills bee larvae 3 days old or younger.

Another is the Varroa mite, Varroa destructor (pic left), a tiny mite which attaches itself to a Honeybee and then sucks hemolymph (insect blood) from the bee. The bites leave wounds which become infected, leading to a disease called varroatosis, against which Honeybees have virtually no resistance. The Varroa mite is native to Asia, and has spread worldwide over the past 50 years, reaching the continental US in 1987.

Another is the Varroa mite, Varroa destructor (pic left), a tiny mite which attaches itself to a Honeybee and then sucks hemolymph (insect blood) from the bee. The bites leave wounds which become infected, leading to a disease called varroatosis, against which Honeybees have virtually no resistance. The Varroa mite is native to Asia, and has spread worldwide over the past 50 years, reaching the continental US in 1987.

A more recent threat is the much-publicized Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD) which has had a dramatic impact on US hives over the last 3-5 years. With CCD, a colony basically just ups and flies off, abandoning the hive. Unlike with varroatosis and other pathogens, there are few if any dead bees left behind, and strangely Wax Moths and Hive Beetles, which typically move quickly into abandoned hives, usually leave CCD-afflicted hives alone for several weeks.  There’s not a clear consensus on the cause of CCD; diseases, fungi, varroatosis, pesticides and even genetically-modified foods have all been proposed. But one leading (though very controversial) suspect is imidacloprid (IMD), a pesticide used on sunflowers, cotton, corn, potatoes, apples pears and many other crops, and exposure to which seems to impair the behavior or “judgment” of bees. France banned IMD in 1999, and since 2005 there’s at least some evidence that CCD there may be abating and Honeybees returning.

There’s not a clear consensus on the cause of CCD; diseases, fungi, varroatosis, pesticides and even genetically-modified foods have all been proposed. But one leading (though very controversial) suspect is imidacloprid (IMD), a pesticide used on sunflowers, cotton, corn, potatoes, apples pears and many other crops, and exposure to which seems to impair the behavior or “judgment” of bees. France banned IMD in 1999, and since 2005 there’s at least some evidence that CCD there may be abating and Honeybees returning.

In any case, I’ve never visited a tidier house than Bev’s; I think she and her new bees will get along just fine. With some “help” from me.

Accessing the peak requires 2 hours of rough, tedious un-paved driving from Mesquite. I mention this because it meant that at the “trailhead”, I was 2 hours from help, and almost 3 hours from a hospital. Before I left my vehicle, I left a sunshower

Accessing the peak requires 2 hours of rough, tedious un-paved driving from Mesquite. I mention this because it meant that at the “trailhead”, I was 2 hours from help, and almost 3 hours from a hospital. Before I left my vehicle, I left a sunshower