So how does a Sowbug Killer get past a Woodlouse’s armor? After the shameless cliffhanger I left you with Wednesday, it had better be a good story. And you know what? It is.

Tangent: I have to break these TdF-type posts up oftentimes because I just can’t steal enough time away in a day to bang the whole thing out. I wish that weren’t the case, because I usually get the idea for a post pretty quickly after I learn about something. But I can’t magically just “spray” the idea onto the screen; I have to piece it together, write text to support it, then build my Expand-O-Graphics. Time, time, time. When you get down to it, the Secret of Life is this: the only thing you are given in life is time. The only thing you have to figure out in life is what to do with the time you have.

The short answer is that there are multiple ways to kill a Woodlouse, and the method employed depends on the particular species of Dysdera spider. Which brings us back to species.

The Amazing Story of Dysderid Evolution

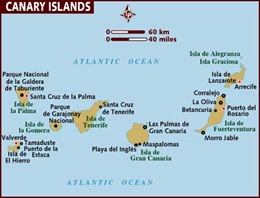

In Part 1 I mentioned in passing that D. crocata is 1 of more than 200 species of Dysdera, and that it’s the only one with a worldwide distribution. All the rest are limited to a “Greater Mediterranean” region, which includes several island chains off the West coast of North Africa. That in itself is interesting enough- 200+ species, only 1 outside of the home region- and that one is all over the world. Far out- eh?

But it gets even weirder when you look at their distribution across those Atlantic island chains.

Side Note: The Canaries are interesting for lots of other reasons. Canary Island flora has a few other head-scratchers like the Dysdera thing, and the archipelago is loaded with dozens of species of endemic snails, beetles and millipedes.

It appears that the Canaries have been a secondary center of Dysdera of evolution in the same way that Mexico may have been a secondary center of Pinus evolution- some pioneers got there, then speciated and radiated. The endemic Dysderids of the Selvagens, the Cape Verdes and (possibly) the Madeiras all appear to be descended from Canary-based ancestors. (The Azores species looks likelier to be the result of a separate colonization from the mainland.)

Extra Detail: An interesting question is how these original colonists got to the Canaries, as they arrived long before people were sailing around in boats. Many juvenile and/or smaller species of spiders travel long distances via “ballooning”, where they trail strands of silk that are caught by wind currents, lifting and carrying them through the air. But no Dysderid has ever been known to balloon. A more plausible dispersal mechanism would be rafting via seaborne mats/clumps of vegetation/debris/soil washed out to sea. Such mats/”floating islands” often emerge from the mouths of rivers in rainy season.

But the rivers that flow out to Morocco’s Atlantic coast, which pass through arid, relatively low-vegetation areas, don’t produce such “floating islands” of vegetation/debris/soil. But in the not-too-distant past, Morocco had a much different climate- cooler, wetter and more forested, and some of the river valleys have topologies which suggest much greater, more powerful flood flows in times past.

Wow. What a totally cool story. But what already does any of this have to do with eating woodlice??

How To Kill A Woodlouse

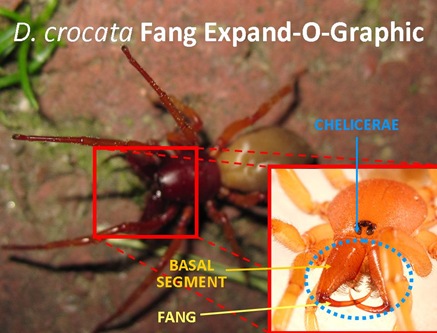

I’m getting there. Now it turns out that these 200+ Dysderids, though overwhelmingly running hunters, have adapted to various hunting techniques, environments and lifestyles*, including both choice of prey and method of attack, and some of those adaptations can be seen in their chelicerae (fangs)**.

*A few Dysdera species are partially or completely troglodytic. D. unguimmanis, which is native to Tenerife, is unique in the genus in that it has no eyes. It spends its days deep inside dark ocean caves.

**Spider cheliceraea are thought to also vary in some species as a result of sexual selection. But in all known Dysdera species, chelicerae morphology is the same across age and gender, so it’s thought not to be the case with these guys.

To review, chelicerae- which we looked at when discussing Tarantulas in the Oquirrh Mountains- are mouthpart/appendages used by arachnids to grasp and handle food; in spiders (order Araneae) they’ve evolved into hollow venom-injecting fangs. Spider chelicerae have 2 segments- the base, and the fang. Across Dysdera species the form and length of both segments vary considerably and seem directly related to both choice of prey and method of attack.

Pincer

The first method is the Pincer tactic, which is used by those species with the longest fangs, and is the method used by our own local SKiller, D. crocata. These guys run quickly up to a woodlouse, turn their “heads*” sideways and pince the woodlouse with their fangs. The upper fang doesn’t pierce the prey; it just provides leverage against the woodlouse’s armored back. The lower

*Spiders don’t really have “heads” of course. What they pivot is their cephalothorax, one of the 2 body segments of a spider, the other being the abdomen.

Now this doesn’t always work right away; sometimes the woodlouse succeeds in rolling up in a ball first. When this happens different species try different tricks. Some will pick up the “ball” with their forelegs and turn it over and around repeatedly, searching for a gap between the plates into which they can work a fang. But others will simply sit and wait. After a short while- usually less than a minute- an undisturbed woodlouse will typically unroll, enabling another attack.

It gets even better- the species D. abdominalis gently taps a woodlouse with its front legs before an attack, which seems to somehow calm the creature and dissuade it from rolling up. It’s like a hypnotic vampire attack from a horror movie!

When you read various sources about spiders, you’ll often read something to the effect of, “Spiders can’t eat solid food…” making their habit of injecting digestive juices into their prey to liquefy it sound like a way of compensating for a handicap- the lack of an extensive internal digestive system. But when you think about it, it’s not a handicap, but an advantage.

Large carnivores like us and mountain lions* and wolves consume mainly vertebrate prey which we must eat from the outside-in, because the flesh is on the outside, and the bones on the inside. But spiders eat invertebrate prey which must be eaten from the inside-out, because the bones are on the outside. Now if your food is nicely contained in a hard, (more or less) watertight exoskeletal container, why not digest it right there, instead of growing, maintaining and lugging around a large, complicated, metabolic-intensive internal digestive system which is prone to various distress, discomfort, blockages, cancers, etc.? We unfortunately don’t have that luxury, because our meat isn’t nicely packaged in convenient containers (and also because we’re not strict carnivores) and so we lug around all this extra, complicated, problem-prone equipment. We’re like campers who drag those big-ass RV/motorhomes all over the place, while spiders are like lightweight, lie-down-on-the-ground-not-a-care-in-the-world-Excellent-Campers. Spiders are way cool.

*I finally stopped saying “cougar”. Just got tired of all the jokes. I thought the slang was dumb and kept hoping it would pass by, like ”Don’t go there…”, or “You go girl!…” but unfortunately it seems to be sticking around.

Fork

The second method is the Fork tactic, which is employed by Dysderids with basal chelicerae segments that are concave on the upward-facing/top side.

Key

The third method is the so-called Key tactic, used by Dysderids with fangs that are thin, flat, and fairly elastic. In this method the spider attacks not the soft underside, but the heavily armored back of the rolled-up woodlouse, probing with a single fang until it is able to work it into a tiny gap between two of the armored plates, like a key into a lock.

And then in between these 2 extremes are species that effectively hunt woodlice, but happily hunt other prey as well.

*I so need to do a post on rats.

Pretty cool story for a spider on a patio.

Note about sources: Special thanks to my friend and fellow nature-blogger KB for research assistance. Info about distribution of Dysdera species and the phylogeny and natural history of Dysderids in the Canary Islands came from this paper. Info on the woodlouse-hunting tactics and Dysderid chelicerae morphology came from this paper. Info on the eyes of woodlice came from Lander University’s Invertebrate Anatomy Online site. D. crocata fang-zoom photo inset came from bugguide.net.

5 comments:

I'm glad you posted the final today. It would have been torture to wait over the weekend. Don't worry about splitting up posts, it worked fine and that would have been a looong single post.

Woodlouse will consistently unroll in my hand after a while, so it's easy to believe would do unroll with a still spider nearby.

Lots of cool details in this post. So many amazing stories all around us.

I'm surprised these spiders aren't more common where you are. I see them all the time here in Stansbury Park. Seems like every time you pick up a rock or move a log they're there. Also spotted several in our unfinished basement.

Oddly enough these rather ugly red spiders never seem frightening to me like other spiders. I thought of them as slow-moving, but maybe I've just never seen one in action. I assume they're not dangerous to humans?

And speaking of which, do sowbugs cause humans any harm? I mean they're everywhere but is there any reason to even try to control them? I now think of them as little lobsters instead of bugs. Luckily I'm not into eating lobster.

Hey Watcher,

I was taking pictures of a tree, like a week ago. you mentioned botany.

If you see any interesting or mysterious plants, or other organisms on your travels, let me know...

healthyhomegardening.com

-Search for "Greenspire Tree"

Thanks

Gardengeek.

El Guapo- No, they’re harmless. The bite hurts, but it doesn’t do any real damage. Maybe not scary because not hairy? Woodlice: totally harmless- don’t spread disease, don’t eat our food, or wood. I actually love lobster, and try not to think of them as big bugs… BTW, here’s my theory on lobsters: if they could squeal like a cat or a dog, no one would ever manage to get them into a pot.

Gardengeek- Hey thanks for stopping by and thanks for the pointer. Was great running into you last week and I’ll be spending some time over on the site!

Those red-orange spiders totally gross me out. Other spiders - no problem. I think it is because their abdomens look like big fat wood tics. I was hoping they were a nuisance to humans, so I wouldn't feel bad if I killed one on instant reaction to their hideousness, but now I have to be careful and nice. I hate pill bugs too, so in that respect I should make friends with the ugly orange SKillers and let them do their thing. At least now with knowledge of their great biology story thanks to this blog, I can appreciate their evolutionary prowess while being grossed out.

Post a Comment