Note: This one is long. I probably should have broken it up into multiple parts, but since it’s already a part of a longer series, I felt that would be hierarchically problematic. And anyway, I just felt like banging it out. Oh, and sorry about the title- I guess I’ve driven past one too many KOAs…

Two cool things about sleeping outside close to the solstice is that 1) you wake up early naturally, and 2) it’s not particularly cold when you wake, so you don’t procrastinate around getting out of the bag and moving. So I was fed, packed up, back in the car and rolling before 7AM on Saturday. Dropping back down through Red Canyon to join US89, I followed the Sevier River South, and gradually up. As the land rose the fields and meadows by the river- really more of a stream now- became greener, and the trees alongside taller. At around 7400 feet, a mile before the junction of US89 and Highway 14, the Sevier splits into 2 tributaries, Minnie Creek and Tyler Creek, veering away/upstream from the road at roughly 45 degrees on either side. About another mile up, just before the crest of the hill, a final little spring, Gravel Spring lies downhill a few hundred feet to the left, the very last, uppermost, teeniest water source of the mighty Sevier Basin.

Long Valley Junction is a 3-way junction with a restaurant/gas station, like a gazillion others in the rural West, but it marks a border. On the North side of the hill, all water flows down into the Great Basin, specifically Sevier Basin, which after the Great Salt Lake and Humboldt basins, is one of the most extensive and varied drainage basins in all of the Great Basin. From here a spilled cup of water will wind its way up past Red Canyon, through Panguitch, Junction and Richfield, before bending to the West, crossing under I-15 North of Scipio, the angling Southwest past Delta and out into the emptiest and bleakest of valleys, an ephemeral playa called “Sevier Lake”, evaporating in the hot sun under the watchful crags of the House Range.

Side Note: After you blog for a while, you have posts you think back on as good or not-so-good. And then there are some that you thought were just an amazingly great idea, but didn’t materialize the way you had hoped. One of my early posts in this third category was this post, where I described a road trip across US50 in Nevada in terms of hydrological basins we passed through over a 2-day road trip. I’m not sure it ever really clicked with any readers (and in fairness pretty much nobody read this thing back then) but I always felt that the idea for the post was terrific; I think a hydrological view of the West turns our traditional mental maps inside out, as we think about watercourses, connections, the paths they form and the places they lead to.

Down I drove on 89, through Orderville, Glendale and in Kanab, where I gassed up before continuing into Arizona, then angling East toward the Kaibab.

I love driving up onto the Kaibab Plateau. Over the course of maybe 15 minutes you go from wide-open desert-scrub dotted with Prickly Poppies, to shady, cool Ponderosa forest. By the time you pull into Jacob Lake, the desert is already fading into memory.

Virtually all parts- stems, leaves, flowers, roots- of Prickly Poppies are loaded with alkaloids and that’s why they’re often the only flower around in heavily-grazed areas- cattle won’t touch them.

Biologically, the Kaibab Plateau is an island, bounded an all side by deserts and/or canyons, most notably the

*Both White Fir, which we know well from the Wasatch, and Corkbark Fir, Abies lasiocarpa var. arizonica, which we don’t get here in Utah.

**Primarily Engelman, but some Blue Spruce as well.

When you pass by/round one of the points*, the sudden vista reminds you where you are and what you’re doing- zipping along the rim of the world’s greatest canyon on a bicycle. It’s hard to stay on the trail then, and well worth stopping for a moment. But something else changes besides the view at each point, and that’s the forest.

*The trail takes in 5 major “points”- Timp, North Timp, Locust, Fence and Parrisawampitts. But in between are several minor points, each with an inspiring canyon view. I didn’t keep count, but I’d guess that there are 10-12 decent canyon viewpoints along the entire trail.

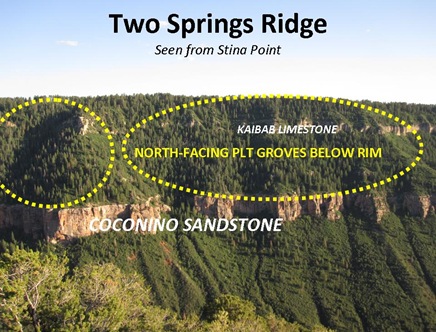

Side Note: The Ponderosa/P-J division at the rim is somewhat of a generalization, as the forest type boundaries vary locally by aspect. In this photo (below), I’m looking South from my campsite on Stina Point toward the North-facing slope of Two Springs Ridge, on which we can see extensive groves of PLTs (probably Douglas Firs.)

But wait- the best is yet to come! At 2:44, as we’re angling around to the East/Southeast, we pass through a virtual corridor of blooming Cliffrose. How lovely is that? The clip ends with us re-entering the Ponderosa forest.

Side Note: This ride was quite possibly the best-smelling ride I’ve ever been on. The dominating scent was the rich pine-smell of the Ponderosa forest, brought out in force by the mid-afternoon sun, and spiced with the occasional hint of vanilla*. But on the occasions where the trail passed through a blooming Cliffrose corridor, an almost sickly-sweet honey-like smell washed over me, and for a moment on each of the points, I caught the hot dry, Juniper-y scents of the benches and draws below. About a year ago I did a post on smell. After this ride I found myself wishing I’d saved the topic for the Kaibab.

*A number of websites and guidebooks will tell you that only Jeffrey Pine- and not Ponderosa- smells of vanilla, and that this is a certain way to tell the 2 apart. It’s not true. Though the vanilla smell is more common and generally stronger in Jeffrey Pine, you can often pick it up in Ponderosas on a warm day, especially (so it seems) from larger trees.

Trees!

In describing the flora of the Kaibab,

*I explained pinnately-compound in this post. BTW, the Goldenrain trees around Salt Lake just started to bloom.

**But the thorns of the Kaibab locusts are nowhere near as problematic as Mesquite, and certainly nothing like the nightmare of the various Southwest acacias. One guidebook to the Rainbow Rim recommends wearing long sleeves when cycling past Locust Point (where the namesake trees are especially profuse) but the warning’s totally overblown. Besides, thorns grab and shred soft fabric much more readily than they do skin. Basic info on the structure of thorns, BTW, I covered in this post. (Man, it is like I have a post for everything.)

Later in the summer, the fertilized flowers will develop into peapods. But like Lupine, you can’t eat them- they’re poisonous. Which brings me to…

If Only I Had Known…

Here’s something that’s happened at least a dozen times over the course of this project: I’ll see something interesting far from home and take a photo. I’ll go home and ID it, then get curious and read all about it. And oftentimes, when I do, I’ll find out something really interesting about the plant or bug or bird or rock or whatever in question, and I’ll think, “Damn! If I’d only I’d known that when I was in front of it…”

Rocks!

We’ll come back to the Kaibab’s biological isolation in a moment, but first let’s return to that point we pedaled past, and the amazing view we glimpsed. Everybody knows of course that one of the most remarkable things about the Grand Canyon is the geology it exposes*. I won’t give the canyon’s geology a full treatment in this post**, but it’s worth pausing at the points and thinking for a moment about what we’re riding on.

*What? You didn’t know that?? OK, I’m sorry- you’re not smart enough to be reading this blog.

**For 3 reasons: 1) This post is long enough. 2) the geology of the Grand Canyon totally deserves its own post (which I will not have time to get to this week) and 3) Arizona Steve and I are cooking up a Grand Canyon backpack for the Fall which will provide a much better, up-close opportunity for a Grand Canyon geo-post. I am telling you, the secret of happiness in the West is to be always scheming your next adventure. Tickets on the fridge, baby!

To an amateur- like me- who learned most of his geology in Southern Utah, this is the single weirdest thing about the Canyon- the rocks are all wrong! Everything I know from Southern Utah- the Entrada Sandstone of Arches and Bartlett Wash, the Navajo Sansdtone of Robber’s Roost, Zion and the Slickrock trail, the Wingate cliffs of Twin Corral Box, the Shinarump of Gooseberry and the the Moenkopi formation of JEM trail- gone. Gone, gone, gone. The rock I was riding on riding on yesterday up on the Pausaugunt- at the same altitude and just ~100 miles or so North- the Claron Formation, was laid down 200 million years later than that what I’m riding on the Rainbow Rim. This same Kaibab Limestone was up there as well yesterday, but it was about a mile and a half under my wheels!

This effect, of older rock layers being exposed at the surface as one moves South down through Utah and into Northern Arizona is the “Grand Staircase” referenced in our namesake national monument. By the time you get down to the Kaibab Plateau, the rocks newer than 250 million years have all been eroded away.

When you look down into the canyon, you’re looking at dozens of stories like this- of erosion, of seas and deserts past, all the way down to the very spines of once-Himalayan-sized mountain ranges so ancient as to pre-date multicellular life itself.

Extra Detail: Just 2 layers below the Kaibab Limestone, you can see a prominent vertical layer of beige cliffs. This is the Coconino Sandstone, which was a Sahara-like desert of sand dunes some 270 million years ago. Further on down several layers more, the high red cliffs- generally the tallest and most vertical throughout the canyon- are the Redwall Formation, formed at the bottom of an another ancient- but longer-lasting- sea.

One of the most interesting aspects of GC geology is how the canyon formed- not just the rocks, but the canyon itself. There’s not a 100% agreed-upon answer, but it seems likely that some number and combination of major rivers has been eroding down through the rock layers for around 17 million years. The current course of the Colorado River is only thought to have been in place for some ~5 million years. Before this time the Eastern and Western portions of the canyon were different drainages being eroded by different rivers, until the Western/lower river “captured” the Eastern/upper river. The route- and even direction- of the ancestral Eastern/upper river is unclear, but most geologists feel that part of its course was through Marble Canyon and the Little Colorado River.

Down at the bottom of the canyon- the very bottom*- the dark gray cliffs alongside the river are Vishnu Schist**, the worn-down, ~2 billion year old core of long-since forgotten, soaring range of mountains. Every layer of rock in the GC has a fantastic story to tell.

*If you haven’t been to the bottom of the canyon, you should put it on your bucket list. Hike down, take a river trip, whatever. Just don’t do a mule*** trip. I swear the tourists on those things always look freaking miserable.

**I just love this name- “Vishnu Schist.” It’s cryptic and forbidding and enticing all at the same time. All week long I’ve been looking for an opening to use it in a conversation.

***Someday I will do a post on mules.

*Seriously, that section could’ve been a post in itself. This blog is so chock-full of value, it makes my head spin. (It’s also why it takes me so damn long to finish a post.)

Critters!

The biological isolation of the plateau impacts animal life as well, a good example being the Kaibab Squirrel, Sciurus aberti kaibabensis, a subspecies of a familiar friend from my old home in Colorado, Abert’s Squirrel. A Kaibab Squirrel basically is an Abert’s Squirrel- a large, pointy-eared Sciurid that feeds on the seeds, buds and inner bark of Ponderosas- with a different color scheme. It has the same bushy tail and tufted ears (though the ear tufts often aren’t noticeable in summer), but the tail is light gray/white, the body dark gray and the belly black. Abert’s Squirrel is common on the South Rim, and across Northern Arizona, New Mexico and much of Colorado. But the Kaibab Squirrel lives on the Kaibab plateau- specifically in the Ponderosa belt of the plateau- and no where else in the world.

Extra Detail: The subspecific phylogeny of S. aberti is a lot more complex than the simple Kaibab vs. Abert division implied by the guidebooks. The Kaibab Squirrel is actually one of 6 generally recognized subspecies. The all-black version I was familiar with in Colorado is S. aberti ferreus. The Abert’s Squirrels of the South Rim, which look very different with white belly and grey body, are S. aberti aberti. There’s another subspecies in Northwestern New Mexico, and then 2 more down in Northern Mexico. It used to be assumed that the 6 subspecies diverged fairly recently during the Wisconsin Glacial Episode, or roughly within the last 100,000 years or so. But genetic research indicates that the subspecies diverged much earlier, probably somewhere between 900,000 and 1.5 million years ago.

But the more interesting thing is this: The Kaibab and South-Rim Abert’s Squirrels (S. aberti aberti) appear to be more closely-related (and recently diverged) to one another than they are to any of the other subspecies, which is curious, because the leading cause of such divergences was thought to be geographic barriers, and it’s hard to imagine a much more formidable barrier in the North American West than the Grand Canyon*…

*Which has been at its current depth for the last 1.2 million years.

Anyway, I’ve read about the Abert/Kaibab/South/North Rim thing in probably a dozen different books, guides and pamphlets over the years, and it so it’s annoyed me for a while that I’ve been down to the North Rim several times over the past 20 years and never spotted one. I mean seriously, here I am, Mr. Nature, always out in the boonies and spotting interesting blooms and birds and bugs and rocks and lichens, but I can’t spot a damn squirrel?

On the ride back, my heart leapt at a possible quick glimpse, which you can (barely) spot here dashing across the trail and in to the stump.

But a clear sighting/photo- for the moment- eluded me. I re-mounted and pedaled the last couple of miles back to Timp Point.

I wanted to camp on/near the rim, but the choice spots at Timp Point were full up. I’d spotted several open sites at North Timp Point, and had it in my mind to drive back up there for the night, but on a whim I headed for the next point South- Stina Point.

*Probably not suitable for a passenger car, though a Subaru-type vehicle would make it easily.

Tangent: There was another thought on my mind as I drive out to Stina Point- the Watchermobile. The Watchermobile is a 2000 Toyota 4Runner. I love the vehicle. Though the paint is pocked and the seats cracked, it’s been reliable, versatile and taken me to all sorts of places. I take great care of it* and am meticulous about scheduled maintenance. But it’s 11 years old and has 156,000 miles. Like a human body, no matter how well cared for it is, eventually something will break. Which wouldn’t be a big deal, except that I often take it to some pretty remote, lightly-traveled places.

*By “great care”, I mean mechanical care, not making love to it with a bottle of Turtlewax. If you ever encounter the Watchermobile, you will likely notice that a) it is dusty/muddy and b) the interior smells a bit like bike grease and sweaty outdoor clothing/gear (in other words- sort of like me toward the end of a road trip). But it runs great.

Now at this point in the tangent, you’re probably thinking, “Oh yeah, I get it- he’s worried about being stranded out in the boonies…” But that’s not what I’m worried about at all - I’m worried about totaling my vehicle. Not through an accident- but through towing charges. Let me explain:

In the backcountry I almost always have a mountain bike and plenty of water with me, and I’m almost never more than 50 “road” miles from pavement. If I get stuck I’ll just ride out*. But the thornier issue I what to do with the 4Runner.

*Mud would be more problematic. But with adequate water and a sleeping bag, waiting 2 or 3 days for the ground to dry out or freeze wouldn’t be life-threatening.

From time to time tourists break down in really remote locations, like the Maze (in Canyonlands National Park) for instance. When they do, there are towing services in towns like Moab and Kanab that have high-clearance 4WD wreckers that can come get them out. But these outfits charge on an hourly basis, and the going in many of these locations is slow. So when your Tahoe or Landcruiser or Hummer breaks down on the White Rim or at the bottom of the Flint Trail, it’s not inconceivable that the tow out could end up costing you a few thousand dollars.

Painful as this is, ultimately to get your $40,000 SUV out, it’s worth spending $3K or so- there’s no other practical option. But when your SUV is 11 years old and worth more like 5 or 6K, the math starts to get more problematic. And this brings me to the point- eventually, in the not-too-distant future, should I keep my beloved 4Runner, the cost of a tow could “total” the vehicle.

I parked in a wide Ponderosa Grove

Note about sources: Most of the geological info in this post came from Bob Ribokas’ Grand Canyon Explorer site, Annabelle Foos’ Geology of Grand Canyon National Park, North Rim, Stephen Whitney’s Field Guide to the Grand Canyon, and Halka Chronic’s Roadside Geology of Utah. Info on S. aberti genetics and subspecies came from the paper Phylogeny of Six Sciurus aberti Subspecies Based on Nucleotide Sequences of Cytochrome b, Peter Wettstein et al, 1994. Thanks to friend and fellow nature blogger KB for research assistance.

If you’re interested in learning more about squirrels in general, I recommend Christopher’s recent post over at Catalogue of Organisms. Closer to home, I blogged about Red Squirrels here in the Wasatch in the Fall of 2008.

10 comments:

Still working my way through the awesome post but thought I would address the 4Runner while I was still thinking about it. My 1997 4Runner has 237K miles on it and its still running strong, despite how much I beat it up (I take it off road to reach destinations for biking/hiking/camping but don't take it places solely to 4X4). I didn't have any mechanical issues until it reached 200K.

In other words, your 4Runner (with 156K miles) is still just being broken in. So salvage value should not just take into account trade in value but life expectancy and emotional attachment (yep, I love my 4Runner and will drive it until it dies, although I expect to get another one in the next year or so to have a dependable truck for longer forays into the backcountry).

mtb w

Wow, a marathon. But good stuff. I want to ride that trail.

I see your point about the expense of getting towed out of a remote location. My first approach would be to fix the vehicle on site and drive it out. But that's because I've worked on cars and my brother does some 4-wheeling where making field repairs is normal. So if you break down out in the boonies, give me a call, or better yet invite me along.

All that about geology and plants and animals, and all we can talk about is your 4Runner. But I concur with mtb w and Kris. Even if the cost of tow/repair is more than the vehicle's value, if it's less than the cost of replacement, it's probably still worthwhile.

Plus retrieving your vehicle is a good excuse for another adventure. I'm sure that if you called Kris and/or me and said "hey I need you to go rent a flatbed trailer and haul it down to the Kaibab plateau to get my 4Runner out" we'd be all over it. And all that would cost you is gas/trailer money and a couple rockstars for the drive home.

Well these are certainly encouraging comments. Thanks mtb w and SBJ for the wise and supportive counsel.

And KKris- you're an Excellent Camper and a 4WD mechanic?? Oh man, I am taking you along everywhere!

I'm just like Anonymous - same vehicle and same year but slightly fewer miles. In fact, we have two of them, but different colors. What great vehicles that have had only tiny problems so far! Unbelievably, thought, our 4wd van handles rough driving better than a 4runner due to its incredible horsepower. We are shocked.

As for the Abert's Squirrel, I have to admit to not actually reading the paper and already discarding it. But, I have grey/white belly Aberts, a chocolate Aberts, and a black Aberts in my yard. It sounds like those are all subspecies?

We're seeing something that I've read was happening to Aberts squirrels and is bad. Fox squirrels are forging higher, and we now have 1-2 of them around our house at various times of year. The Aberts disappear when they arrive... Perhaps the Fox Squirrels are aggressive toward them? But, I've read that the upward migration of Fox Squirrels is threatening Aberts squirrels. People ascribe this trend to global warming, letting the Fox squirrels live higher but I'm a little skeptical that the temperature has changed enough in the past decade to make a difference.

KB- According to the range map in the paper, all of your Aberts should be ferreus. The “all-black” reference was my own observation- and a bit of an over-generalization- from my old neighborhood in Evergreen (made 15 years ago, when I was largely clueless about, well, everything.) According to the 2003 Forest Service Technical Conservation Assessment, 68% of the Aberts in North-Central Colorado are black.

The same assessment, BTW, briefly mentions- though seemingly downplays- the Fox Squirrel threat, claiming that although Fox Squirrels now live at up to 9,000 ft in the Front Range, they “do not directly compete for life requirements.” But sounds like you’re seeing a bigger impact.

Thanks for the post and the references.

The local rocks I ride on are 1.5 billion years old. Sort of blows the mind.

Wow... I need to start setting time aside in my day for posts like this... This was an ultramathon - but very good indeed.

I'm now eagerly looking forward to your future post about the formation of GC. I have always been a bit skeptical of the typical river erosion formation theory. Erosion, yes. But how could a ~20’ wide river carve vertical walls into “bedrock” (sorry for the bad generic term) 4-12 miles wide? Why isn’t the Mississippi another Grand Canyon? Its average daily flow is far greater than any peak flow of the Colorado, and it is in soft soils – no bedrock to cut through?

One theory that I find a bit easier to understand is the Cataclysmic Flood Theory. Originally put forth by J Harlen Bretz http://www.detectingdesign.com/harlenbretz.html That basically during the last (few) ice age(s) a giant ice dam(s) formed, holding back a virtual inland ocean, and as it thawed/broke, it unleashed huge torrents that carved the entire landscape including the canyons, in a relatively short amount of time. National Geographic did a great show/investigation into it http://natgeotv.com/uk/earth_shocks/about To me, it answers many other landform formation issues as well as the canyons in a single theory.

Unfortunately, creationists have clamored to this theory to try to prove that the earth isn’t as old as scientists think. Not sure how “proving” that the GC could have been made in the last few thousand years “proves” that they earth is only a few thousand years old – when the rock it is cutting through is millions of years old. So unfortunately, when you google it, you get a lot of that crap – which cheapens the theory. But, I still think it is a good one, and hope you will touch on it.

Chad- thanks for the interesting comment. Bretz has certainly been vindicated with the whole Lake Missoula/Channeled Scablands thing. (That quote to his son when he got the Penrose medal was money!) But I think it’s still a stretch to tie CF to the GC. Different rocks, far deeper, and no evidence of a conveniently located massive pro-glacial lake.

Something interesting about the GC is that the date of its origin has recently been pushed back- way back- to around 17 million YA, as a result of new dating techniques just within the last few years. Even this time period though is only about 1/3 of the time that the Colo Plateau has been uplifting, which is probably the biggest difference between the GC and the Mississippi Valley- the plateau has been lifting up as the river (or rivers, until ~5M YA) ran through it.

In any event, stay tuned. I hope to pull together the backpack in late September, which would be a nice opp to get into the geology in more detail.

Very cool post; especially the geology parts. I get all trippy about continental divides. I especially like the divide through North Dakota between the Hudson Bay drainage and the Mississippi. In places, it is literally so flat a tennis ball wouldn't roll off a slab of Vishnu Schist if it were laid on the ground there.

P.S. I have been so busy I have not been able to keep up with your awesome posts, but I am slowly getting caught up. Looking forward to the next few posts about your weekend in geology heaven.

Post a Comment