OK, one more Montana post, then it’s time to admit that my vacations are over, summer is (almost) done and I have to get used to being back home and going to work every day.

Tangent: This was one of the toughest vacations I can remember to come home from. I’ll pick up this tangent again at the end of the post…

Today I want to blog about 2 more vacation-related things that really don’t really have anything at all in common except that a) they both happened on the same day, and b) they were both really cool. Plus the second one involves my wife, and I am always looking for excuses to blog about her.

Our last full day in Whitefish I woke early to mtn bike (what else is new) before the family arose. The weather had prohibited dawn rides every day except for the first day in Missoula, and so I was eager to get out. I had to think carefully about the ride; 3 days of rain probably meant some messy trails. So I picked the Big Mountain Ski area, North of town.

Ski areas often have wide, mellow-grade, lawsuit-proof trails, and I thought such a trail might give me the climb I was looking for and some nice views without being a total mud-fest. It turned out to be a good choice. The trail was fine, if not great, I got in a good climb and a nice long descent. But the thing that totally and completely made the ride was the clouds.

Ski areas often have wide, mellow-grade, lawsuit-proof trails, and I thought such a trail might give me the climb I was looking for and some nice views without being a total mud-fest. It turned out to be a good choice. The trail was fine, if not great, I got in a good climb and a nice long descent. But the thing that totally and completely made the ride was the clouds.

Tangent: No, this isn’t the continuation of the first tangent- that’s coming later. And it’s not nested either. It’s just a whole other tangent.

Usually when visiting a new area, ski area trails are my last choice. They tend to be excessively tame, over-signed, and often- as a result of lift-served traffic- over-used. They’re also oftentimes not very scenic or wilderness-y, traversing chopped-down slopes and criss-crossing various roads, lifts, buildings and machinery.

For the first 3 miles, the Summit Trail up Big Mountain realized those fears. It was chopped up and re-routed and overlapped with crappy, un-scenic service roads. But after 3 miles, the trail became very scenic, a nice-quality- if tame- true singletrack that rarely intersected lifts or roads and offered fine views for another 5 miles.

Being inside clouds is always cool. Sometimes, depending on where you are, you may find yourself driving or hiking through a cloud, and though it may be a bit cold and damp and spooky, it’s always a memorable experience. Being above clouds is also way cool, especially when you’re on the ground (versus in an airplane.) Looking down at the tops of clouds, you can’t help but get a “getting away with something” feeling; you’re up high in bright sunlight with clear air and hundred mile views, seeing a world concealed from the clouded valleys below.

Being inside clouds is always cool. Sometimes, depending on where you are, you may find yourself driving or hiking through a cloud, and though it may be a bit cold and damp and spooky, it’s always a memorable experience. Being above clouds is also way cool, especially when you’re on the ground (versus in an airplane.) Looking down at the tops of clouds, you can’t help but get a “getting away with something” feeling; you’re up high in bright sunlight with clear air and hundred mile views, seeing a world concealed from the clouded valleys below.

Sometimes you end up biking through clouds, maybe on the road, maybe on dirt. But the absolutely coolest- but-rarest cloud mtn bike ride is the Complete Cloud Deck Double Traverse (CCDDT), where you start below the cloud base, climb up into the clouds, then all the way through and above the cloud tops before returning back down through the deck all over again. A real, true CCDDT is both rare and wonderful, and you don’t forget it.

Sometimes you end up biking through clouds, maybe on the road, maybe on dirt. But the absolutely coolest- but-rarest cloud mtn bike ride is the Complete Cloud Deck Double Traverse (CCDDT), where you start below the cloud base, climb up into the clouds, then all the way through and above the cloud tops before returning back down through the deck all over again. A real, true CCDDT is both rare and wonderful, and you don’t forget it.

Tangent: Coastal readers may be thinking, “What’s the big deal? I bike up out of clouds all the time…” Not quite. You probably bike up out of marine fog, which is also way cool, but different. In a Marine Fog Climb (MFC)*, you start out in the fog, which you climb up and break out of, into the sunlight. But in CCDDT you start out in clear air, below the cloud base, with good visibility. And when you return, you break out of the bottom of the clouds while descending, a weird-but-cool converse of breaking through the tops of the clouds on the way up.

*On a vacation in Santa Barbara several years ago I did several early morning MFCs, and enjoyed them thoroughly.

Nested Tangent: Fog is of course also way cool, and  totally worth a post or two (or more) of its own. There are actually several different types of fog, including marine fog, radiation fog (forms at night, as the land radiates heat built up during the day) and inversion fog (pic right), which I blogged about last winter. Coolest, weirdest- and perhaps most dangerous- of all are the dreaded ice fogs of the Arctic and Antarctic.

totally worth a post or two (or more) of its own. There are actually several different types of fog, including marine fog, radiation fog (forms at night, as the land radiates heat built up during the day) and inversion fog (pic right), which I blogged about last winter. Coolest, weirdest- and perhaps most dangerous- of all are the dreaded ice fogs of the Arctic and Antarctic.

The Ride

The Summit trail starts up at 5,000 feet. The sky was filled with the low, still clouds that linger the morning after a big storm front has moved through. From the parking lot I could see that the cloud base was well below the summit, and I wondered if the view would be socked in. I started climbing.

As I wound my way up across ski slopes and service roads, the cloud base loomed closer. Soon the air grew cold and damp. The tops of the Lodgepoles were obscured in mist, and a few moments later, at around 5,800 feet, I was enveloped in cloud. I thought about how mysterious and otherworldly it always feels inside of a cloud.

I thought about how beautiful the PLTs looked shrouded in fog. But mostly what I thought was the bottoms of clouds, and why, in a given area, they’re so darn flat. Seriously, why does cloud just appear at a certain level as you climb up? Why aren’t clouds just floating around at all different levels- some high, some low, some in between? Why is the cloud base in a given area at a given day/time so freaking uniform?

I thought about how beautiful the PLTs looked shrouded in fog. But mostly what I thought was the bottoms of clouds, and why, in a given area, they’re so darn flat. Seriously, why does cloud just appear at a certain level as you climb up? Why aren’t clouds just floating around at all different levels- some high, some low, some in between? Why is the cloud base in a given area at a given day/time so freaking uniform?

But before we can understand why clouds sit where they do, we have to understand just exactly what a cloud is.

All About Clouds

I conducted an experiment for this post*. I asked 4 coworkers- all smart people**- to tell me what a cloud was made of. All said “water vapor”, which is not the case. Water vapor is water (H2O) in gaseous form. It’s all around us all the time, and the concentration of it in the air is defined as humidity.

*Because even though I have absolutely no scientific background, experience or qualifications, sometimes I like to make pretend.

*The first 2 were Matt and Sid, both of whom I’ve blogged about previously. And the other 2 were IT guys, so you know they’re wicked smart.

Clouds- the big white fluffy things that you see up in the sky- are liquid water, in the form of droplets. Notice that I didn’t say “drops”- I said “dropLETS.” What’s the difference? Size, mainly. A typical raindrop has a diameter of about 2 millimeters. A typical water droplet has a diameter of 20 microns- 1/100th that of a raindrop.

Because they’re so small, droplets are held aloft by updrafts of warmer air rising from the surface. Water droplets form around a nucleating particle, typically a micron or less in diameter, that can be anything from pollen to dust to pollutants from exhaust or fires. As more and more droplets form, they tend to clump together into larger droplets, and eventually raindrops, which can no longer be supported by the updrafts and fall to Earth, but I’m getting ahead of myself.

Because they’re so small, droplets are held aloft by updrafts of warmer air rising from the surface. Water droplets form around a nucleating particle, typically a micron or less in diameter, that can be anything from pollen to dust to pollutants from exhaust or fires. As more and more droplets form, they tend to clump together into larger droplets, and eventually raindrops, which can no longer be supported by the updrafts and fall to Earth, but I’m getting ahead of myself.

Side Note: This “nucleation-aggregation” process is pretty much the same deal by which snowflakes form, and which I detailed in this post.

OK, so why does the water vapor condense into liquid, and why does it do so at a particular altitude? Because that altitude- the bottom of the clouds- is the altitude at which the dew point occurs on that given day, at that given hour.

What’s Dew Point?

The dew point is the temperature at or below which water vapor condenses into liquid*. This temperature is dependent on humidity, so on a humid day (>50% humidity) the dew point might be in the high 60s F, while on a dry day (<30% humidity) it might be down in the 40s F. (When the dew point temp falls below freezing it’s called the frost point.)

*Actually, this statement is pretty kiddie-simplistic, as- for that matter- is this whole explanation. In the real world water vapor is condensing into droplets, and droplets are evaporating into vapor, constantly. The dew point is really the point at which condensation of vapor out-paces evaporation of droplets. You don’t really need to know this- I just stuck it in as a CYA in case some weather-geek stumbles across this post.

Dew point can be calculated (sample graph right, not mine) through an equation which I am not going to reproduce here because a) it’s way complicated and you don’t really care, and b) I can’t figure out how to type those Greek letters on my keyboard. But here’s an approximation that’s good enough for hacks like me:

Dew point can be calculated (sample graph right, not mine) through an equation which I am not going to reproduce here because a) it’s way complicated and you don’t really care, and b) I can’t figure out how to type those Greek letters on my keyboard. But here’s an approximation that’s good enough for hacks like me:

Dew Point Temperature = Dry Bulb Temperature* – ((100 – Relative Humidity)/5)

*Dry Blub Temperature = air temp with no exposure to radiation or moisture.

Anyway, as you go up, the air gets colder, and when you get high/cold enough to hit the dew point, clouds start to form. In the absence of strong winds, storms, or other violent weather, that altitude will be pretty uniform in a given area, and that’s why the cloud base (bottom) is so flat.

I climbed up through the mist. For me riding in a cloud seems to distort not only distance, but also time, and

I climbed up through the mist. For me riding in a cloud seems to distort not only distance, but also time, and  I found myself glancing repeatedly down at my watch and/or bike computer to re-orient myself time-wise. The forest thinned and opened up, with scattered stands of trees punctuating the open slopes. I passed close to one tree, a pine, and absent-mindedly expected to confirm it as yet another Lodgepole, but it wasn’t. It was 5-needled.

I found myself glancing repeatedly down at my watch and/or bike computer to re-orient myself time-wise. The forest thinned and opened up, with scattered stands of trees punctuating the open slopes. I passed close to one tree, a pine, and absent-mindedly expected to confirm it as yet another Lodgepole, but it wasn’t. It was 5-needled.

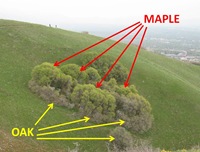

Botany-Tangent*: It was Whitebark Pine, Pinus albicaulis, and this was my first sighting of it*. A new pine! Whitebark actually isn’t all that unusual in the West; it occurs widely in the Northern Rockies, in the Sierra, and in several ranges across Nevada. It just doesn’t occur in Utah.

Botany-Tangent*: It was Whitebark Pine, Pinus albicaulis, and this was my first sighting of it*. A new pine! Whitebark actually isn’t all that unusual in the West; it occurs widely in the Northern Rockies, in the Sierra, and in several ranges across Nevada. It just doesn’t occur in Utah.

*Technically, I’m sure it wasn’t my first sighting- it was the first sighting I recognized. I know that I was in and among Whitebarks in the Ruby Mountains (Nevada) for 3 days several years ago on a backpack, but that was back when I was still plant-blind.

It looks a lot like Limber Pine, and the 2 can be tough to tell apart. The bark is slightly different, and there are a few other geeky little differences, but cones are the best ID tool. Whitebark cones look different, and they don’t fall from the tree; rather they’re picked apart by nut-seeking Corvids, particularly Clark’s Nutcracker. When no cones are present, you can hunt around on the ground underneath for old, fallen cones. If you find them, it’s probably a Limber Pine.

It looks a lot like Limber Pine, and the 2 can be tough to tell apart. The bark is slightly different, and there are a few other geeky little differences, but cones are the best ID tool. Whitebark cones look different, and they don’t fall from the tree; rather they’re picked apart by nut-seeking Corvids, particularly Clark’s Nutcracker. When no cones are present, you can hunt around on the ground underneath for old, fallen cones. If you find them, it’s probably a Limber Pine.

Whitebark Pine is completely dependent on corvids (and overwhelmingly Clark’s Nutcracker) for reproduction and the 2 share a fascinating history. As the American West’s most highly evolved Bird Pine and Pine Bird, their story is one of the best examples of co-evolution around. (A tale which I related in this post last year if you’re interested.)

Whitebark Pine is completely dependent on corvids (and overwhelmingly Clark’s Nutcracker) for reproduction and the 2 share a fascinating history. As the American West’s most highly evolved Bird Pine and Pine Bird, their story is one of the best examples of co-evolution around. (A tale which I related in this post last year if you’re interested.)

*Because you didn’t really think I was going to make it through a whole post without going off about some plant or other, did you?

More Whitebarks appeared, and… Oh, wait a minute.

TIMEOUT: OK, I just realized- I’m sucking up the whole post (and running out of time) with the Cloud-Ride. OK sorry- the Awesome Wife-Meets-A-Bear story will have to wait till the next post. I’m sorry. Really. I never think these posts are going to run on as long as they do.

OK, back to the ride. Where was I? Oh yeah- the cool, breaking-out-of the clouds-science-meets-happy-karma part.

More Whitebarks appeared, and the sky started to lighten (pic left); I was approaching the cloud top. At around 6,400 feet I entered a weird sunlight netherworld of blue sky above and sun-yellowed mist all around me, which I pedaled through for another ¼ mile before breaking out into full sunlight. After 3 days of clouds, fog and rain, the direct unbroken morning sunlight was almost painful; as I pedaled I squinted, grimaced and squirmed for a moment like some nocturnal creature dragged out into the light of day.

More Whitebarks appeared, and the sky started to lighten (pic left); I was approaching the cloud top. At around 6,400 feet I entered a weird sunlight netherworld of blue sky above and sun-yellowed mist all around me, which I pedaled through for another ¼ mile before breaking out into full sunlight. After 3 days of clouds, fog and rain, the direct unbroken morning sunlight was almost painful; as I pedaled I squinted, grimaced and squirmed for a moment like some nocturnal creature dragged out into the light of day.

Updrafts raise the water droplets until the warm air cools to a point where it no longer rises strongly enough to support the weight of the water. But updrafts and invections aren’t uniform, and for this reason, the tops of clouds are generally much less even than the bottoms. The tops of clouds, BTW, are where actual raindrops (or snowflakes) form.

Updrafts raise the water droplets until the warm air cools to a point where it no longer rises strongly enough to support the weight of the water. But updrafts and invections aren’t uniform, and for this reason, the tops of clouds are generally much less even than the bottoms. The tops of clouds, BTW, are where actual raindrops (or snowflakes) form.

Side Note: I’ve wondered for this reason if the air inside of a cloud shouldn’t feel damper/colder/wetter shortly before the top, but if it does I haven’t noticed.

My eyes finally adjusted, and I rode the last couple of gently-climbing miles to the summit feeling warm and happy in the bright sun. At the top I lingered for a few minutes, looking around in all directions, but my eyes were most often drawn to the East and North, to the Lewis Overthrust, to the park, to the high, jagged peaks rising above the sea of clouds, toward Canada and the unknown Northern lands beyond.

My eyes finally adjusted, and I rode the last couple of gently-climbing miles to the summit feeling warm and happy in the bright sun. At the top I lingered for a few minutes, looking around in all directions, but my eyes were most often drawn to the East and North, to the Lewis Overthrust, to the park, to the high, jagged peaks rising above the sea of clouds, toward Canada and the unknown Northern lands beyond.

I turned around and began the long descent back down into the clouds.

Next Up: OK, I’m really going to tell the bear story next… And I’ll finish that first tangent, too.