Since I've been back in town, it's been a good week for wildlife. Here's a Moose shot from Friday morning up in Pinebrook. On the same ride I came across 2 either Coyotes or Kit Foxes (not sure) that were too fast to photograph, and I've had a couple of Porcupine close encounters in the past week as well. And separately, I may have found a new hybrid Gambel/Turbinella Oak up in Jeremy Ranch yesterday. More on that in a future post.

Since I've been back in town, it's been a good week for wildlife. Here's a Moose shot from Friday morning up in Pinebrook. On the same ride I came across 2 either Coyotes or Kit Foxes (not sure) that were too fast to photograph, and I've had a couple of Porcupine close encounters in the past week as well. And separately, I may have found a new hybrid Gambel/Turbinella Oak up in Jeremy Ranch yesterday. More on that in a future post.

Back to Aspen

Aspen, like Cottonwoods, are dioecious, so plants are either male or female. And as such clones are either male or female as well. (Pando is male.) There’s some evidence (but not absolutely clear) that male clones grow bigger and faster than female clones. There’s also been the suggestion that polyploid Aspen tree/clones grow bigger trunks and leaves than standard diploid Aspen, (See this post for explanation of polyploidy in plants.) but this is even sketchier than the male/female thing. What does seem to be certain is that polyploidy is fairly common in Aspen. In one study of 18 Utah Aspen clones, 14 were found to be diploid (i.e. “normal”), 3 were triploid and 1 was tetraploid. (Diploid/”normal” for an Aspen is 38 chromosomes. Or in genetic language, n=19.)

Aspen, like Cottonwoods, are dioecious, so plants are either male or female. And as such clones are either male or female as well. (Pando is male.) There’s some evidence (but not absolutely clear) that male clones grow bigger and faster than female clones. There’s also been the suggestion that polyploid Aspen tree/clones grow bigger trunks and leaves than standard diploid Aspen, (See this post for explanation of polyploidy in plants.) but this is even sketchier than the male/female thing. What does seem to be certain is that polyploidy is fairly common in Aspen. In one study of 18 Utah Aspen clones, 14 were found to be diploid (i.e. “normal”), 3 were triploid and 1 was tetraploid. (Diploid/”normal” for an Aspen is 38 chromosomes. Or in genetic language, n=19.)

Cloning, or specifically “suckering” also gives Aspen a weird sort of 9-lives-ish immortality; even when a stand is completely leveled- through, clear-cut, fire or avalanche- the clone is often reborn the following year, in a sea of suckers. In fact, oftentimes you’ll notice that nearly all of the trees in a given clone seem to be of similar age and size; most likely that’s because they’re from suckers that all popped up around the same time, following some significant event.

Tangent: In the Park City area, I’m pretty sure that “significant event” was clear-cutting. Most 19th-century Western mining towns laid waste to surrounding forests to fuel smelters, as I mentioned last week when talking about Pinon in Central Nevada.

Though clones can lives for millennia, individual trees aren’t terribly long-lived. The average tree in Pando is about 130 years old, and the very oldest Aspens are around 300 years old. Very old Aspen can grow up over 4 feet in diameter and over 120 feet high. The biggest Aspen I’ve seen aren’t in the Wasatch, but down South on the high plateaus and ranges (Markagunt, Aquarius, Abajos, La Sals.) (Pic left = an oldie/biggie from an isolated grove on the Paunsaugunt, bike for scale.Yes I know this bike-against-tree photo theme is getting old but what can I say? I come across a lot of big trees by myself and I need something for scale…) The real oldies lose their smooth white bark on their bottom 3 or 4 feet, and it becomes dark gray and deeply furrowed.

Though clones can lives for millennia, individual trees aren’t terribly long-lived. The average tree in Pando is about 130 years old, and the very oldest Aspens are around 300 years old. Very old Aspen can grow up over 4 feet in diameter and over 120 feet high. The biggest Aspen I’ve seen aren’t in the Wasatch, but down South on the high plateaus and ranges (Markagunt, Aquarius, Abajos, La Sals.) (Pic left = an oldie/biggie from an isolated grove on the Paunsaugunt, bike for scale.Yes I know this bike-against-tree photo theme is getting old but what can I say? I come across a lot of big trees by myself and I need something for scale…) The real oldies lose their smooth white bark on their bottom 3 or 4 feet, and it becomes dark gray and deeply furrowed.

Another Amazing Cloning-Related Semi-Factoid: For years botanists have dinked around studying the regional differences between Aspens across North America. One fascinating aspect of this regional variation seems to be the differences between populations that reproduce primarily sexually, such as those up in Montana, and those that reproduce clonally, such as those here in Utah. And the thinking is that at least part of the reason for the variation is that the sexually-reproducing Aspen have continued to evolve and adapt, while the clonally-reproducing aspen are genetic copies of the Aspen that were around tens of thousands of years ago, with only a handful of possible sexual generations in between. If this is truly the case, it means that our Aspen here in Utah are in a sort of “evolutionary stasis”, stalled out as it were, while the wider world of sexually-reproducing Aspens moves on down the road of evolution…

The gray bark is thought to be caused by 1 of 2 things, or both. First is gnawing. Decades of animals- voles, sheep, deer- the bark to get at the cambium scars the tree, and the scars develop into deep gray furrows. The Second possibility is snow; 3-4 feet is typically how high the snow lies against the truck for much of the winter, and over century or so it might contribute to scarring.

Speaking of scarring, another unique thing most everyone knows about Aspen is how well and for how long they display carvings in their bark. Many popular trails through Aspen groves are virtual time capsules that trigger various “I wonder whatever happened…” thoughts. (“Bill loves Katie 1973”. What happened? Did Bill and Katie stay together? Did they marry? Are they still together? Alive?)

In the Wasatch, the oldest carving I’ve found is from 1936. Nearby there’s a wonderful little clearing with several carvings from 1943 and 1944. It’s a frequent resting-spot for me, and I think about the boys how were there 65 years ago, while WWII raged. What became of them? Are they still alive? Have I passed their grandchildren on the trail? On the freeway? At the mall?

Across the valley in the Oquirrh Mountains I came across a carving from 1928 up Ophir Canyon a few years back. But the oldest carving I’ve come across, still clear and legible, was from 1902. I found it on the Virgin Rim Trail, down on the Markagunt Plateau, in 2002. I assume (hope) it’s still there. I used to have a digital photo, and regrettably, seem to have lost/deleted it…

Tangent: I’ve never carved my initials- or anything else- in an Aspen. I never regretted doing so until 2 years ago. In August 1993 I biked the Aspen Loop trail in the Abajo Mountains West of Monticello. The trail was lined with Aspen-carvings dating back into the late 1950’s. I toyed with carving my initials, but thought, “Ah, who would ever want to see initials carved in the 90’s?” In June 2006, I finally rode the same trail again, and found myself wishing I’d carved those initials…

By the way, the white powder on the bark of Aspen (which will work as a poor-man’s sunscreen in a pinch) is comprised of dead cork cells.

By the way, the white powder on the bark of Aspen (which will work as a poor-man’s sunscreen in a pinch) is comprised of dead cork cells.

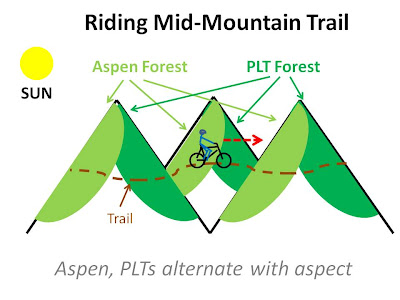

Aspen are shade-intolerant, and in the Wasatch, they dominate on south-facing slopes above 7,000 feet, while PLTs (see this post for acronym definition) generally dominate North-facing slopes at similar altitudes. A wonderful place to see this is along the Mid-Mountain Trail in Park City, particularly along the stretch between The Canyons ski resort and Pinebrook. Over and over again, as it hugs the backside of the Wasatch at 8,000 feet, the trail passes from sunny, grassy, light Aspen grove to deep, dark, shaded Fir/Douglas Fir forest and back again, flickering back and forth between the two worlds.

Where aspect is less clearly defined, Aspen mixes with PLTs in the Wasatch, most often in a losing battle of succession. While Aspen are not shade-tolerant, many Wasatch PLTs- White Fir, Douglas Fir, Engelmann Spruce- are, and barring further disturbance, they’ll eventually come to dominate many Aspen glades.

The last obvious unique characteristic of Aspen I’ll mention is their sound. 4 months ago, back in canyon country, I mentioned the soft swishing/rustling of Fremont Cottonwood leaves. Aspen leaves have a the same leaf-stem architecture- narrow side-to-side, thick up & down- which causes the same pleasant rustling, but at a higher pitch, due to the smaller size and lesser thickness of Aspen leaves. This slightly higher-pitched rustling sounds almost like a chorus of soft whispers in a gentle breeze, and when you’re alone, and half-paying attention, you can almost be caught off-guard at times by the sound, as though someone is telling you something you can’t quite catch, but maybe could, if you stopped and somehow listened more closely.

Aspen are so amazing and wonderful on so many levels. Their visual and sonic beauty, their history and mystery, and their strange distortion of light and space and sense of time all combine to impart a sense of restorative wonder that for me one of the great pleasures of living by the Wasatch, and the Beauty of the World in its purest form.